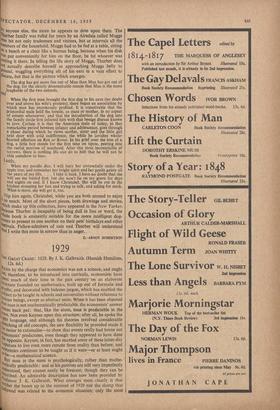

1929

by the charge that economics was not a science, and ought N. therefore, to be introduced into curricula, economists have 'Pent much of their time in the past century on an elaborate fracture founded on mathematics, built up out of formula, and '111)11s, and decorated with hideous jargon, which has enabled the ;11bfeet to be taught in schools and universities without reference to 1,°11tan beings, except as abstract units. When it has been objected . 'at man is not mathematically predictable, the economists' answer eOateS back pat : that, like the atom, man is predictable in the mass. Not even Keynes upset this structure; after all, he spoke the IOlt language, and although his theories involved considerable stretching of old concepts, the new flexibility he provided made it far easier to rationalise—to show that events really had borne out °nomists' predictions, even though they appeared to have done the opposite. Keynes, in fact, has enabled some of these latter-day r' "aPutans to live even more remote from reality than before; and i-"tlomics continues to be taught as if it were—or at least ought t0 be--a mathematical science.

rlititlt man in the mass is psychologically, rather than mathe- o4tieally predictable : and as his motives are still very imperfectly followed was related to the economic situation; only the most pderstood, they cannot easily be forecast; though they can be eseribed. An admirable description has now been provided by Professor J. K. Galbraith. What emerges most clearly is that (either the boom up to the summer of 1929 nor the slump that egregious hindsight can find links between them. There was no economic—in the ordinary sense of the word—reason why the initial recession in 1929 should not have reversed itself, as it had done in 1927, and has since done again. Booms and slumps are not related to economics, but to gambling; it is the gambler's instinct that blows up a South Sea Bubble. A boom is the product of the same mood that causes chain letters to circulate, or provides the invitations to pyramid clubs; the mood R. L. S. caught in The Bottle Imp. 'At some time in the growth of a boom all aspects of property ownership become irrelevant, except the prospect of an early rise in price,' and where stock exchanges do not possess, or fail to use, machinery for curb- ing the gambler, the boom—and the crash—follow.

Professor Galbraith's great merit is that he sees economics as commonsense study; he is not taken in by all the nonsense that has led, and which still leads, to university economists being called upon as experts, when in fact the subject about which they are expert has about as much relevance to modern conditions as phlogistonism. Unkindly, Professor Galbraith has pulled in a number of pronouncements by the expert of 1929, Professor Irving Fisher, who announced on the brink of the slump that the country's economy had reached a 'permanently high plateau,' and that he expected to see the stock markets 'a good deal higher yet: The book incidentally, is full of unexpected entertainment of this kind; and at least a couple of phrases are coined that deserve to go into general circulation. The 'bezzle,' for example: Professor Galbraith's word for the inventory of undiscovered embezzlement which at any given moment exists in—or, more precisely, not in' the country's businesses and banks; it may reach staggering Pen" portions in good times, when there is little risk of it being d15' covered before it can be made good, but it is left high and dry by crash. And there is his description of one of the oldest and least understood of industrial rites, the 'no-business meeting' : Men meet together for many reasons in the course of business' . . . But there are at least as many reasons for meetings to transact no business. Meetings are held because men seek 00 panionship or, at. a minimum, wish to escape the tedium of solitad duties. They yearn for the prestige which accrues to the man wko, presides over meetings, and this leads them to convoke assemblan over which they can preside. Finally, there is the meeting will?, is called not because there is business to be done, but because it necessary to create the impression that business is being done. The author concludes with the warning that financiers may not yet fully have learned the lesson of 1929; less because they lac' the instinct of self-preservation than because 'now, as throughout history, financial capacity and political perspicacity are inverseh; correlated.' In general this may be true; but it is not true Professor Galbraith; and it should cease to be true for anybody

who reads this sane, stimulating and entertaining book.

BRIAN INGLIS

Previous page

Previous page