Opera

Fairy Flute

By DAVID CAIRNS HAVING got to know the music of The Magic Flute thoroughly and absorbed its message be- fore I saw ,it on the stage, I could never undergtand, what all the trouble was supposed to be about. The music explains and unifies all. Just as the notoriously heterogeneous ele- ments, Singspiel, opera seria, opera buffa, Italian coloratura, German chorale and counterpoint and popular melody are fused in a single 'Magic Flute style,' so. the different worlds of the plot are seen to be aspects of a common universe. Mozart's score makes real the drama's assump- tions that Sarastro and the Queen, Moriostatos and the Speaker, Tamino and Papageno, the Temples of Reason and Wisdom and Truth and the earthbound mortal 'with a body filled and vacant mind,' are one. The music both sym- bolises and creates this unity.

The work proves in practice difficult to stage; but that is because our culture makes the diffi- culties. The embarrassing juxtaposition of the sub- lime and the slapstick, the 'change of plot' half- way through the first act, the disconcerting fact that the Flute and the Bells and the Genii, sym- bols and messengers of numinous goodness, are the gift of Evil and that the three Ladies who transmit them to Tamino and Papageno utter the most unexceptionable sentiments on the subject of peace and goodwill—these are illusory demons which arise from our asking the wrong questions. It may seem too easy a way out to answer that The Magic Flute must be taken as a fairy tale, but it is the true answer. Somehow we have to purge ourselves of modern superstitions, destructive sophistications, irrelevant complexity, without falling into false naivety; we have, in fact, to let the simplicity and purity of the music (which Mozart achieved with no hint of artificiality) take hold of us and guide us.

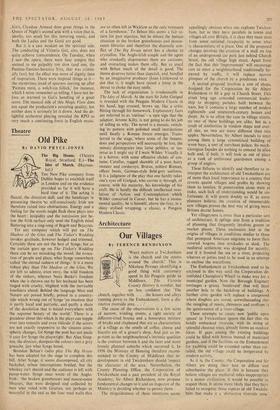

This is what few productions are able to do, and what the producer and designer of the new Glyndebourne Magic Flute, Franco Enriquez and Emanuele Luzzati, have to a remarkable ex- tent succeeded in doing. They have treated the work, unpretentiously, as a pantomine in which the sublime is not insisted on but allowed to appear as a natural element among many. It is a world in which nothing is surprising and every- thing wonderful. One accepts, for example, the fact that Tamino does not actually play the flute, merely passing it through the air in front of him, or that there is no palpable tree for Papageno to hang himself on.

The fantasy has an eager childlike quality. The Genii are smiling children trotting softly on web feet, and riding hobby horses with faces like kindly lizards and palm leaves sprouting from their heads. It is an idea that at first startles, perhaps even shocks, but seems increas- ingly touching and righ't. Papageno, having re- freshed himself with the god-given liquor, sings his aria 'Ein Madchen oder Weibchen' to the enormous goblet, still dangling in front of him and then tantalisingly whisked out of sight at the end of his song. The tables which eventually materialise to appease his hunger are a white- clothed schoolboy's dream, glutted with every imaginable good thing. The beasts who come out at the sound of Tamino's playing are charming cartoonist's lions and egrets, responding with little darting movements to every fresh phrase of the flute. The Queen of Night is a doll-like creature with fixed, black-ringed eyes, and bat wings which look like tiny arms raised in permanent frustrated fury. Tamino carries a bow of precise, dreamlike delicacy and beauty, Pamina wears the white nightgown-like robe of the young fairy-tale princess in distress.

The settings have the bright, direct, semi- abstract character of children's art. They consist largely of triangular mobile pillars (though there is also a deep-recessed cavern glistening with a dim, beguiling light for the Queen of Night's domain, glimpsed at the back of the stage in the , early scenes). The pillars are painted in bold pat- terns on each of their sides to represent different facets of the drama, and moved in a moment by invisible stage hands.

In this way the scenes follow each other with- out a break (as is essential to any adequate realisation of the work's unity-in-diversity), while the columns among which the characters wander suggest the maze of human ignorance and un- certainty that clears to reveal the width of the open stage only in the final scenes of enlighten- ment. I do not find all the decor equally success- ful. The final scenes, when the pillars have vanished into the wings, are in some, ways the least successful. The rich, flamelike colours of the priests' costumes are too elaborate, par- ticularly that of Sarastro, who looks like some trapper king gone Aztec. But in general this is easily the best staged Magic Flute I have ever. seen.

If sublimity is rarely.touched, this is for musical reasons which have nothing to do with the pro-

duction. Carlo Cava's Sarastro is a stolidly un-

imaginative piece of singing, rough 'in line and never illuminating in phrasing, disappointing from the impressive Seneca of Poppea. Judith Raskin's

Pamina is beautifully sung, but a little too easily.

Ronald Bell as the Speaker tries hard but remains prosaic in the great recitative scene which is the pivot of the whole opera. The ensemble is a good one: Ragnar Ulfung's Tamino is finely poised, intelligent singing, with unexpected resources of power, and acting of an elegance and presenta- bility rare in a Mozart tenor, Heinz Blankenburg is a first-rate Papageno whose accent bears signs

of a rather closer acqtraintaince with the German language than his fellow American, Miss Ras-

kin's, Claudine Arnaud does great things in the Queen of Night's second aria with a voice that is, ideally, too small for this towering music, and both the Ladies and the Genii are good.

But it is a cast weakest on the spiritual side. The conducting of Vittorio Gui, also, does not quite achieve transcendence. On Tuesday, when I saw the opera, there were four tempos that seemed to me palpably too slow (and one, the Pamina-Tamino-Sarastro Trio, that was crimin- ally fast), but the effect was more of dignity than of inspiration. There were inspired things in it— the mysterious tread of quavers starting up after Pamina mein, o welch'ein Glfick,' for instance, which I never remember so telling; I have not be- fore so warmed to Gui's handling of a great score. The musical side of this Magic Flute does not equal the production's revealing quality; but neither does it seriously let it down. And the de- lightful orchestral playing revealed the RPO as very much a continuing force in English music.

Previous page

Previous page