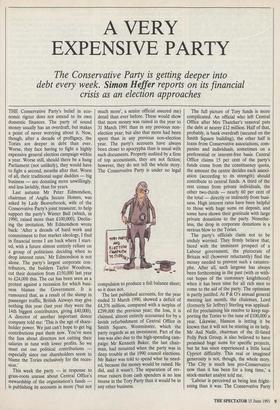

A VERY EXPENSIVE PARTY

The Conservative Party is getting deeper into crisis as an election approaches

THE Conservative Party's belief in eco- nomic rigour does not extend to its own domestic finances. The party of sound money usually has an overdraft, but makes a point of never worrying about it. Now, though, after a decade of profligacy, the Tories are deeper in debt than ever. Worse, they face having to fight a highly expensive general election campaign within a year. Worse still, should there be a hung Parliament (not unlikely), they would have to fight a second, months after that. Worst of all, their traditional sugar daddies — big business — are donating more unwillingly, and less lavishly, than for years.

Last autumn Mr Peter Edmondson, chairman of Anglia Secure Homes, was asked by Lady Beaverbrook, wife of the Conservative Party's joint treasurer, to help support the party's Winter Ball (which, in 1990, raised more than £100,000). Declin- ing the invitation, Mr Edmondson wrote back: 'After a decade of hard work and commitment to free market ideology, I find in financial terms I am back where I start- ed, with a future almost entirely reliant on a group of politicians deciding when to drop interest rates.' Mr Edmondson is not alone. The party's largest corporate con- tributors, the builders Taylor Woodrow, cut their donation from £150,000 last year to £24,000 this. The cut has been seen as a protest against a recession for which busi- ness blames the Government. It is rumoured that, as a result of the slump in passenger traffic, British Airways may give nothing this year (last year they were the 14th biggest contributors, giving £40,000). A director of another important donor company told me: 'This is the age of share- holder power. We just can't hope to get big contributions past them now. You've seen the fuss about directors not cutting their salaries in tune with lower profits. So we must cut our political contributions — especially since our shareholders seem to blame the Tories exclusively for the reces- sion.'

This week the party — in response to grass-roots unease about Central Office's stewardship of the organisation's funds — is publishing its accounts in more (tut not much more', a senior official assured me) detail than ever before. These would show that more money was raised in the year to 31 March 1991 than in any previous non- election year; but also that more had been spent than in any previous non-election year. The party's accounts have always been closer to apocrypha than is usual with such documents. Properly audited by a firm of top accountants, they are not fiction; however, they do not tell the whole story. The Conservative Party is under no legal compulsion to produce a full balance sheet; so it does not.

The last published accounts, for the year ended 31 March 1990, showed a deficit of £4,376 million, compared with a surplus of £299,000 the previous year; the loss, it is claimed, almost entirely accounted for by a lavish refurbishment of Central Office in Smith Square, Westminster, which the party regards as an investment. Part of the loss was also due to the high-spending cam- paign Mr Kenneth Baker, the last chair- man, had mounted when the party was in deep trouble at the 1990 council elections. Mr Baker was told to spend what he need- ed, because the money would be raised. He did, and it wasn't. The separation of rev- enue raisers from cash spenders is no less insane in the Tory Party than it would be in any other business. The full picture of Tory funds is more complicated. An official who left Central Office after Mrs Thatcher's removal puts the debt at nearer £12 million. Half of that, probably, is bank overdraft (secured on the Smith Square building), the other half is loans from Conservative associations, com- panies and individuals, sometimes on a preferential or interest-free basis. Central Office claims 15 per cent of the party's funds come from the constituency quota, the amount the centre decides each associ- ation (according to its strength) should contribute to central funds. A third of the rest comes from private individuals, the other two-thirds — nearly 60 per cent of the total — directly or indirectly from busi- ness. High interest rates have been helpful to those with huge sums on deposit, and some have shown their gratitude with large private donations to the party. Nonethe- less, the drop in corporate donations is a serious blow to the Tories.

The party's officials claim not to be unduly worried. They firmly believe that, faced with the imminent prospect of a Labour government, the plutocrats of Britain will (however reluctantly) find the money needed to prevent such a catastro- phe. After all, such largesse has always been forthcoming in the past (with or with- out hopes of the customary knighthood) when it has been time for all rich men to come to the aid of the party. The optimism is partly justifed. At P & O's annual general meeting last month, the chairman, Lord (formerly Sir Jeffrey) Sterling was applaud- ed for proclaiming his resolve to keep sup- porting the Tories to the tune of £100,000 a year. Likewise, Hanson is letting it be known that it will not be stinting in its help. Mr Asil Nadir, chairman of the ill-fated Polly Peck Group, is also believed to have promised huge sums for specific projects, but he has since experienced a little local Cypriot difficulty. This real or imagined generosity is not, though, the whole story. 'The City is much less pro-Conservative now than it has been for a long time,' a stock-market analyst told me.

'Labour is perceived as being less fright- ening than it was. The Conservative Party is not stroking its supporters in the way it should.' Inevitably, personalities enter at this point. Mrs Thatcher, several industrial- ists told me, was very good at prising money out of people (and not bad, either, at spending it). It is hard to believe Lord King, Chairman of British Airways, would even be thinking about not donating if his friend the ex-Prime Minister still ran the party.

Lord McAlpine, the former joint treasur- er, had a small but fabulously rich clientele whom he could tap for vast sums in an emergency. He is still involved with the Tories' City Liaison Group, but his ab- sences abroad mean he is simply not able to 'stroke' like he used to. Lord Beaver- brook, his charming successor, is regarded as 'not a big mover in the City', according to one company director. Few politicians or businessmen seem impressed with his fel- low treasurer, Lord Laing. With their Board of Finance — led by Major General Sir Brian Wyldebore-Smith and three other retired senior army officers — they repre- sent a staid, outdated fund-raising structure only slowly waking up to the idea of Ameri- can direct mail techniques that might res- cue the income flow.

At the heart of the new resistance to handing over cash, though, is something more significant than personalities. 'The Government's too keen on citizen's char- ters and other irrelevances,' was the view of one formerly large corporate donor. 'Look- ing after big business is not one of its prior- ities. It needs to be more strident about low taxation and more deregulation. There is a perception in boardrooms that the poli- cy has changed.' Deregulation is not always popular, though. Attempts to break cartels in the brewing industry two years ago have still not been forgiven by the brewers, his- torically heroic contributors to Tory cof- fers. Perhaps more worrying still for the party is a point made to me by a corporate public relations specialist, who said he would advise certain clients to think care- fully before donating heavily to the Tory Party in case it compromised them with the next Labour government. Such a govern- ment would, incidentally, legislate to make political contributions by companies con- tingent on the approval of shareholders, which would not necessarily help the Tories.

Lower contributions, for whatever rea- son, could not come at a worse time. Cen- tral Office costs £1million a month to run. Income is probably £750,000 a month at most. The overdraft perhaps costs £150,000 a month to service; so the debt could be rising by as much as £400,000 a month: and that is before the great pre-election morale-boosting campaign for which Mr Chris Patten, the party chairman, is shortly to ask for money. The last election cam- paign cost the Tories £15 million. -Last year, Lord Beaverbrook estimated the next would cost £20 million. Media analysts expect the advertising bill for the Tory campaign to be at least £15 million, though Mr Patten is known to be sceptical about the value of advertising. Even he, though, will have to recognise that the closer the parties, the more necessary advertising will become; and the coming campaign will be very close. In 1987 £3 million was spent on 'wobbly Thursday' alone, when in a fit of panic Mrs Thatcher became convinced the Tories were about to lose (a week later they won by a majority of 100). The pre- election campaign to keep up the heat on Labour until a poll next spring could cost another £3-4 million. The other costs of staff, organisation, transport and communi- cations once the election comes could be another £10 million; all of which suggests the Tories need £40 million to break even, or £30 million just to remain in their pre- sent state of advancing crisis. Perhaps while Mr Lamont, the Chancellor of the Exche- quer, is leaning on the chairmen of the clearing banks to cut the margins on their loans, he is reminding them of one loan in particular — secured on a property in Smith Square — that would benefit from such a reduction.

The banks know that with the recession likely to last some time after the election, prompt repayment of any further loans is unlikely; the situation is positively Mexican. Every penny of the £15 million overdraft facility is likely to be taken up to fight the campaign; other guarantors will be sought for extensions. If the election is not won outright, and another called quickly, the party will face an even worse problem. Recognising the gravity of the predicament the vice-chairman, John Cope MP, a char- tered accountant, works full-time at Cen- tral Office (his recent predecessors were part-time, doubling as ministers of State) and has been undertaking a review of expenditure, looking for cuts even before the election.

If large amounts of money are needed urgently, though, there is another possible source. Although the party's central organi- sation is broke, the party in the country is hugely rich. Mr John Strafford, treasurer of the party's Wessex Area, has calculated that £3 million is earning interest in the deposit accounts of the constituencies in his area alone. Wessex is a rich, but not the richest, region, and the national total could be as much as £15 million. Local fund-rais- ing is successful because of the popular social events many associations run, and the good personal relations between act- ivists and local businessmen. One fund- raising dinner in a recession-hit southern constituency recently raised £17,500 from the 34 guests. However, such cash is salted away because few associations trust it to Central Office, which they regard as exist- ing principally to waste money. At the National Union Executive Committee meeting this week, demands were due to be made for the treasurer (currently appoint- ed by the Prime Minister) to be elected, and a finance committee too, to give the sort of accountability in Central Office that associations want before lending — let alone giving — funds. Preferring the mili- tary junta to democracy, Central Office will refuse. To try to prise more money out of associations the constituency quota pay- ment might be raised, but many local par- ties would ignore such an impost, preferring to leave their funds in the bank for no clear purpose other than 'the rainy day'. At least they will be able to sit in luxu- ry through the years of opposition that could lie ahead, watching the rain pour down on their bankrupt leaders in Smith Square.

'How much for the shot-gunned jeans?'

Previous page

Previous page