BOOKS

Putting the scraps together

Rupert Christiansen

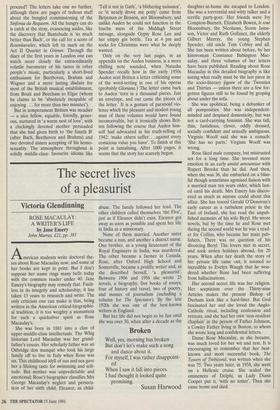

LE 1 I ERS FROM A LIFE: SELECI'ED LE TIERS AND DIARIES OF BENJAMIN BRI TIEN, VOLUME I, 1923-39, VOLUME II, 1939-45 edited by Donald Mitchell and Philip Reed Faber, £75 the set, pp.640 each volume Keenly — and, in some quarters, bit- terly — awaited since his death in 1976, these first two volumes of Britten's letters prove a complex, expensive disappoint- ment. The essential illumination of a genius — perhaps we should not have hoped for that: the major questions about the composer's personality remain un- answered, no sustained articulation of his art emerges, there is an absence of scandal and intimacy. As prose, the 1000-odd pages of text, containing some 500 pieces of cor- respondence, are almost entirely without distinction. If one's attention is gripped, this is because of what can be read between the lines and the editors' magnificent anno- tation of the details. Britten himself may remain a mystery, but his context is authoritatively and fascinatingly document- ed.

Nothing in the books hits harder than the letter Auden wrote to Britten just before he left the US to return to England and Peter Grimes in 1942. It was, I am con- vinced, a crucial and terrible piece of truth- telling which resonated throughout the rest of Britten's life:

Wherever you go you are and probably always will be surrounded by people who adore you, nurse you, and praise everything you do. Up to a certain point this is fine for you, but beware. You see, Bengy dear, you are always tempted to make things too easy for yourself in this way, i.e. to build yourself a warm nest of love (of course, when you get it, you find it a little stifling) by playing the lov- able talented little boy. If you are really to develop your full stature, you will have, I think, to suffer, and make others suffer, in ways which are totally strange to you at pre- sent, and against every conscious value that you have; i.e. you will have to be able to say what you never yet had had the right to say — God, I'm a shit.

Auden also nails the sexual problem and its relation to Britten's creativity in a ratio- nale that he would only fully address and accept 30 years later when he came to Death in Venice:

Bohemian chaos alone ends in a mad jumble of beautiful scraps; bourgeois convention alone ends in large unfeeling corpses ... For middle-class Englishmen like you and me, the danger is of course the second. Your attraction to thin-as-a-board juveniles, i.e. to the sexless and innocent, is a symptom of this. And I am certain too that it is your denial and evasion of the demands of dis- order that is responsible for your attacks of ill-health, i.e. sickness is your substitute for the Bohemian.

This is as close to Britten as one gets. The letters which might have brought him one stage closer are infuriatingly cut, pre-

sumably as the correspondent in question, still living, has his reasons for wishing aspects of the relationship to remain con- cealed (it is not, however, hard to recon- struct the gaps).

Yet I wonder whether Britten's attract- ion to `thin-as-a-board juveniles' hasn't been over-dramatised, or at least over- eroticised. In his introduction — an oddly rambling essay — Donald Mitchell suggests that Britten 'did not discard his childhood so much as preserve it intact within him'. This is perceptive. Britten liked boys because he remained one himself; but he also triumphantly managed to run that side of himself in tandem with a deep and fulfilled marriage to Peter Pears — their passionate, silly, frantic letters to each other are very moving, and I hope someone rubs the faces of Dame Elaine Kellett- Bowman and her kind in their power and honesty. The mutual inspiration of creator and interpreter is surely a phenomenon without parallel in the history of music: 'get the golden [voice] box back in its proper working order again', Britten writes to his `honeybunch'. 'Something goes wrong with my life when that's not functioning proper- ly.'

We learn something, but not much, about the slow evolution of this bond, and a little more about the war years in the US. There was never much doubt in Britten's mind that he had to get back to England as soon as he could — 'the more I think of Snape', he wrote, even as he sailed west- wards, 'the more I feel a fool to have left it at all'; and he was ultimately drawn back as much by revulsion at the vulgarity of the Hollywood element of America — 'so narrow, so self-satisfied, so chauvinistic, so superficial, so reactionary, and above all so ugly' — as by the famous discovery of a volume of Crabbe's poems in a Los Angeles bookshop.

The matter of Auden's influence and its rejection remains obscure, not least because Auden threw Britten's letters away. My own guess is that there wasn't in the 1940s a 'split' at all, only a cooling off, which was partly a matter of geographical distance and partly the familiar reluctance to be exposed to somebody who likes telling you what's what about yourself. Britten is not to be blamed for shrinking from Auden's aesthetic and psychological bullying. 'Ben is like water in our hands', Isherwood told Spender. Wystan and I can do anything we like with him.' But the com- poser of Peter Grimes and the lover of Peter Pears became tougher than that.

Britten was too much of a natural, too little the egoist, to have any compulsion to write much about his own music, except when making the necessary arrangements for its performance or publication. Why did John Ireland fail him as a teacher? What, precisely, did he learn from Frank Bridge? How did the collaborations with Auden on Paul Bunyan and Slater on Peter Grimes proceed? The letters take one no further, although there are pages of tedious stuff about the bungled commissioning of the Sinfonia da Requiem. All the hungry can do is catch at the stray, evanescing asides, like the discovery that Buxtehude is 'so much better than Bach', or the call for a score of Rosenkavalier, which left its mark on the Act II Quartet in Grimes. Through the diary of the first years in London one can watch more closely the extraordinarily volatile barometer of his tastes in other people's music, particularly a short-lived enthusiasm for Beethoven, Brahms and Wagner and a more lasting disdain for most of the British musical establishment, from Boult and Beecham to Elgar (whom he claims to be 'absolutely incapable of enjoying. . . for more than two minutes').

But in temperament Britten was steadier — a nice fellow, equable, friendly, gener- ous, nurtured in 'a warm nest of love', with a cluckingly devoted mother persuaded that she had given birth to 'the fourth B' (after Bach, Beethoven and Brahms) and two devoted sisters accepting of his homo- sexuality. The atmosphere throughout is solidly middle-class: favourite idioms like 'Tell it not in Gath', 'a blithering nuisance', or 'it nearly drove me potty' come from Betjeman or Benson, not Bloomsbury, and unlike Auden he could not function in the louche mess of the Middagh Street ménage, alongside Gypsy Rose Lee and her empty gin bottle. Tea at 4 pm and socks for Christmas were what he deeply wanted.

Only on the very last pages, in an appendix on the Auden business, is a more chilling note sounded, when Natasha Spender recalls how in the early 1950s Auden sent Britten a letter criticising some of the word-setting in one of his operas (probably Glotiana.) The letter came back to Auden 'torn in a thousand pieces. Just an envelope, and out came the pieces of the letter.' It is a gesture of paranoid vio- lence which the pleasant and modest young man of these volumes would have found inconceivable, but it ironically shows Brit- ten following the course that Auden him- self had advocated in his truth-telling of 1942: 'make others suffer. . . against every conscious value you have'. To finish at this point is tantalising. After 1000 pages, it seems that the story has scarcely begun.

Previous page

Previous page