Between life and death

Francis King

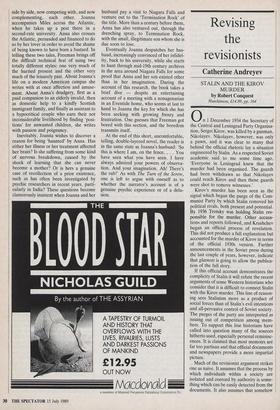

TERMINATION ROCK by Gillian Freeman

Pandora, £12.95, pp.182

The first chapter of this novel, after a one-page introduction in the form of a letter from its female narrator to her husband, begins: 'There was a radioactive pack in my uterus.' There follows a bril- liantly incisive, and therefore chilling, account of how this young woman, wife of an academic, is treated for cancer and, as a consequence, is made infertile. With her, we encounter the kindly, overworked reg- istrar at the hospital, telling her first `You're an intelligent girl, there's absolute- ly no point in not coming to the point' and then 'It's one hundred per cent curable, cancer in the best of all possible places'; the tough Australian woman doctor, her teeth so badly capped that black lines edge her gums, who scolds 'I hear you've been carrying on since you had your biopsy results, but you're tiring yourself and boring us, so be a good girl and pack it in'; the enthusiastic trainee who cries out eagerly 'Oh, may I sew her up? I've never done it before.' All are realised with hard-edged economy.

Once home, both physically and emo- tionally groggy, Joanna begins to suffer odd, disconcerting fugues from her every- day life into another existence in the London of the mid-19th century. She passes an Islington house which seems to her bafflingly familiar. She has brief recol- lections, as though the past were being illuminated by intermittent flashes of light- ning, of a previous existence as a woman called Anna, seduced and made pregnant by the artist who eventually marries her widowed mother. She bicycles out, in all weathers, in search of some traces of this previous existence, thus eventually making her husband, Miles, suspect that she is having a clandestine affair.

Eventually, the two narratives, Joanna's in the present and Anna's in the past, run side by side, now competing with, and now complementing, each other. Joanna accompanies Miles across the Atlantic, when he takes up a post there in a second-rate university. Anna also crosses the Atlantic, persuaded and financed to do so by her lover in order to avoid the shame of being known to have born a bastard. In telling these two tales, Freeman brings off the difficult technical feat of using two totally different styles: one very much of the hurried present and the other very much of the leisurely past. About Joanna's life on a modern American campus she writes with at once affection and amuse- ment. About Anna's drudgery, first as a paid companion to an elderly invalid, then as domestic help to a kindly Scottish immigrant family, and finally as assistant to a hypocritical couple who earn their not inconsiderable livelihood by finding 'posi- tions' for unwanted children, she writes with passion and poignancy.

Inevitably, Joanna wishes to discover a reason for being 'haunted' by Anna. Has either her illness or her treatment affected her brain? Is she suffering from some kind of nervous breakdown, caused by the shock of learning that she can never become a mother? Or is hers a genuine case of recollection of a prior existence, such as has often been investigated by psychic researchers in recent years, parti- cularly in India? These questions become clamorously insistent when Joanna and her husband pay a visit to Niagara Falls and venture out to the 'Termination Rock' of the title. More than a century before them, Anna has also ventured out, through the drenching spray, to Termination Rock, with the small, illegitimate son whom she is due soon to lose.

Eventually Joanna despatches her hus- band, increasingly convinced of her infidel- ity, back to his university, while she starts to hunt through mid-19th century archives in the area around Niagara Falls for some proof that Anna and her son existed other than in her imagination. During the account of this research, the book takes a brief dive — despite an entertaining account of a meeting with a nonagenarian in an Eventide home, who seems at last to hand to Joanna the key for which she has been seeking with growing frenzy and frustration. One guesses that Freeman got bored with this section, and the boredom transmits itself.

At the end of this short, uncomfortable, telling, double-layered novel, the reader is in the same state as Joanna's husband: 'So this is where I am, on the fence. . . . You have seen what you have seen. I have always admired your powers of observa- tion. And your imagination. Ah! There's the rub!' As with The Turn of the Screw, one is left to argue with oneself as to whether the narrator's account is of a genuine psychic experience or of a delu- sion.

Previous page

Previous page