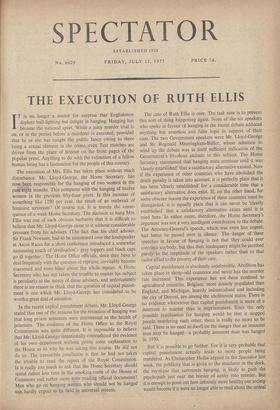

THE EXECUTION OF RUTH ELLIS

IT is no longer a matter for surprise that Englishmen deplore bull-fighting but delight in hanging. Hanging has ' become the national sport:While a juicy murder trial is on, or in the period before a murderer is executed, provided that he or she has caught the public fancy owing to there being a sexual element in the crime, even Test matches are driven from the place of honour on the front pages of the popular press. Anything to do with the extinction of a fellow human being has a fascination for the people of this country.

The execution of Mrs. Ellis has taken place without much disturbance. Mr. Lloyd-George, the Home Secretary, has now been responsible for the hanging of two women in the past eight months. This compares with the hanging of twelve women in the previous fifty-four years. Is this increase of something like 1250 per cent. the result of an outbreak of feminine terrorism? Of course. not. It is merely the conse- quence of a weak Home Secretary. The decision to hang Mrs. Ellis was. one of such obvious barbarity that it is difficult to believe that Mr. Lloyd-George came to it without considerable pressure from his advisers. (The fact that his chief adviser, Sir Frank Newsam, had to be summoned over the loudspeaker at Ascot Races for a short conference introduced a somewhat nauseating touch of 'civilisation': grey toppers and black caps go ill together.) The Home Office official's, since they have to deal frequently with the question of reprieve, inevitably become coarsened and even blasd about the whole matter. A Home Secretary who has not taken the trouble to master his subject is peculiarly at the mercy of these advisers, and unfortunately there is no reason to think that the question of capital punish- ment is one which Mr. Lloyd-George has considered, to be worth a great deal of attention.

In the recent capital punishment debate; Mr. Lloyd-George stated that one of the reasons for the retention of hanging was that long prison sentences were detrimental to the health of prisoners. The evidence of the Home Office to the Royal Commission was quite different. It is impossible to believe that Mr. Lloyd-George intentionally contradicted the evidence of his own department without giving some explanation to the House as to why he was taking this course. He did not do so. The irresistible conclusion is that he had not taken the trouble to read the report of the Royal Commission. Is it really too much to ask that the Home Secretary should spend rather less time in the smoking-room of the House of Commons and rather more time reading official documents? Men who go on hanging women who should not be hanged can hardly expect to be held in universal esteem. The case of Ruth Ellis is over. The task now is to prevent this sort of thing happening again. None of the six speakers who spoke in favour of hanging in the recent debate adduced anything but assertion and false logic in support of their case. The two Government speakers were Mr. Lloyd-George and Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, whose selection to wind up the debate was in itself sufficient indication of the Government's frivolous attitude to this subject. The Home Secretary maintained that hanging must continue until it was `clearly established' that a satisfactory alternative existed. Now if the experience of other countries who have abolished the death penalty is taken into account, it is perfectly plain that it has been 'clearly established' for a considerable time that a satisfactory alternative does exist. If, on the other hand, for some obscure reason the experience of these countries must be disregarded, it is equally plain that it can never be 'clearly established' that a satisfactory alternative exists until it is tried here. In either event, therefore, the Home Secretary's argument was not a very intelligent contribution to the debate. The Attorney-General's speech, which was even less cogent, had better be passed over in silence. The danger of these speeches in favour of hanging is not that they could ever convince anybody, but that their inadequacy might be ascribed purely 'to the ineptitude of the speakers rather than to that factor allied to the poverty of their case.

Capital punishment is absolutely indefensible. Abolition has taken place in thirty-odd countries and never has the murder rate increased. This experience has not been confined to agricultural countries. Belgium, more densely populated than England, and Michigan, heavily industrialised and including the city of Detroit, are among the abolitionist states. There is no evidence whatsoever that capital punishment is more of a deterrent to murder than is imprisonment. Since the only possible justification for hanging would be that it stopped people murdering each other, there is really no more to be said. There is no need to dwell on the danger that an innocent man may be hanged—a probably innocent man was hanged in 1950.

But it is possible to go further. For it is very probable that capital punishment actually leads to more people being murdered. As Christopher Hollis argued in the Spectator last week, the publicity that is given to the murderer in the dock, the mystique that surrounds hanging, is, likely to push the psychopath just over the border of sanity into murder. But it is enough to point out how infinitely more healthy our society would become if it were no longer able to read about the ordeal of people waiting execution, or to gaze at photographs of the families of condemned men visiting the prison, or photographs of the public hangman having a day at the races.

All this has been well known for many years, but we still have hanging. Why? The vast majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party is in favour of abolition; it is the Conservatives who are the supporters of hanging. It is not clear why hanging should be so dear to the Tory mind. The case against it is largely empirical; the case for it is emotional and doctrinaire. It might, therefore, have been expected that the Conservative Party, the party of empiricism, would support abolition. But in the past debate all but seventeen voted for the death penalty.

The execution of Ruth Ellis may do good. Not even the thickest head could have remained unmoved as the monstrous drama moved to its ending in the still summer heat of Wednes- day morning. There is not the slightest doubt that Mrs. Ellis should have been reprieved. As we pointed out last week, it is the prerogative of mercy that keeps hanging alive. The failure of Mr. Lloyd-George and his advisers to recognise this fact can hardly fail to have produced a revulsion amongst the thinking population_ Even Tory MPs will have been affected. Surely the whole practice of hanging will have been brought into disrepute. When Sir Anthony Eden returns from Geneva, he should change his Home Secretary and then introduce legislation. He can be certain that the only sufferers will be the Sunday newspapers.

Previous page

Previous page