ARTS

Museums

Melancholy victory

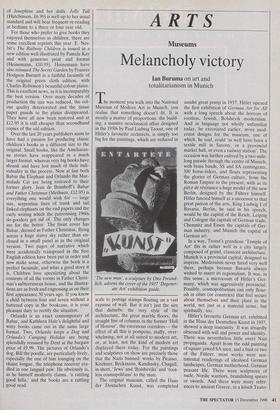

he moment you walk into the National Museum of Modern Art in Munich, you realise that something doesn't fit. It is mostly a matter of proportions: the build- ing, a massive neoclassical affair designed in the 1930s by Paul Ludwig Troost, one of Hitler's favourite architects, is simply too big for the paintings, which are reduced in 'The new man', a sculpture by Otto Freund- lich, adorns the cover of the 1937 'Degener- ate Art' exhibition guide.

scale to postage stamps floating on a vast expanse of wall. But it isn't just the size that disturbs: the very style of the architecture, the great marble floors, the straight line of columns in the former 'Hall of Honour', the enormous corridors — the effect of all this is pompous, stuffy, over- whelming, not at all suited to modern art, or, at least, not the kind of modern art displayed there today. For the paintings and sculptures on show are precisely those that the Nazis banned: works by Picasso, Kirchner, Beckmann, Kandinsky, Chagall, in short, 'Jews' and 'Bolsheviks' and 'root- less cosmopolitans' to the man.

The original museum, called the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, was completed

amidst great pomp in 1937. Hitler opened the first exhibition of German Art for All with a long speech about the horrors of rootless, Jewish, Bolshevik modernism. And in language not wholly unfamiliar today, he excoriated earlier, more mod- ernist designs for the museum, one of which, he said, could 'as well have been a textile mill in Saxony, or a provincial market hall, or even a railway station'. The occasion was further enlived by a two-mile- long parade through the centre of Munich, with brass bands, SS and SA contingents, 500 horse-riders, and floats representing the glories of German culture, from the Roman Empire to the present, with as its piece de resistance a huge model of the new Berlin, designed by the Flihrer himself. Hitler fancied himself as a successor to that great patron of the arts, King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Berlin, he said in his speech, would be the capital of the Reich, Leipzig and Cologne the capitals of German trade, Chemnitz and Essen the capitals of Ger- man industry, and Munich the capital of German art.

In a way, Troost's grandiose 'Temple of Art' fits in rather well in a city largely composed of grand, classicist architecture. Munich is a provincial capital, designed to impress. Modernism never fared very well there, perhaps because Bavaria always wished to assert its regionalism. It was, in this sense, a microcosm of Hitler's Ger- many, which was aggressively provincial. Possibly, cosmopolitanism can only flour- ish in cities (or countries) that feel secure about themselves and their place in the world, not just in a material sense, but spiritually, too.

Hitler's favourite German art, exhibited in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in 1937, showed a deep insecurity. It was absurdly obsessed with will and power and identity. There was nevertheless little overt Nazi propaganda. Apart from the odd painting of square-jawed SA men, and a bust or two of the Fiihrer, most works were sen- timental renderings of idealised German landscapes, German motherhood, German peasant life. There were sculptures of nude, Nordic warriors, brandishing spears or swords. And there were many refer- ences to ancient Greece, in a kitsch Teuto- nic way. Indeed, kitsch is what most of this art was, kitsch in the sense of misplaced symbolism, misplaced religion: an exalted vision of a new order under the Nazis, freely and tastelessly borrowing its imagery from Athens, Rome, Jerusalem and the Black Forest.

Although many people with a residue of sympathy for Marxist politics hate this comparison, you can't help but think of Stalinist art. Of course, there are differ- ences between the Nazi and the communist states: Hitler's Germany produced no art of any consequence, while the Soviet Un- ion, before Stalin cracked down, did. The communist revolution, after all, inspired Eisenstein's cinema and the Constructiv- ists. But stylistically the official art of Stalin's Soviet Union, Mao's China, Kim It Sung's North Korea and Hitler's Germany was so close as to be indistinguishable.

If one were to stage an exhibition of this kind of art, one would trace back its origins not so much to ancient Greece as to the artists who celebrated Napoleon, such as Jacques-Louis David. Idealising great lead- ers, the Nation and the People was the purpose of such art. It was populist as well as pompous, combining the stuffy gran- diosity of 19th-century classicism with the sentimentality of the Romantics. In com- munist nations, as in Nazi Germany, this style froze, drained of what life it might once have had.

The names of the artists so prominently featured in Munich in 1937 are virtually all forgotten. The sculptor Arno Breker still has a kind of camp reputation for his muscle-bound blond athletes. But who now has heard of Carl Horn, who contri- buted a portrait of Rudolf Hess, or of the painter of rural scenes in the Rhineland, Julius Paul Junghanns? And yet their art is not always without skill. Nor can art always be dismissed because it serves particular religious or secular masters. There are few Napoleon-worshippers left, but David's paintings, featured in a huge retrospective in Paris this year, are widely admired. Socialists, as much as conservative populists, often demand that art have a social or political meaning, that it be more than a commodity in the market-place. The avant-garde, as well as many modernists, are frequently criticised for being out of touch with the people, for being bereft of deep meaning, for perpetrating a fraud at vast expense. These were precisely the points raised by Hitler and Goebbels in their philistine diatribes against 'degener- ate art'. This does not mean that every critic of the avant-garde is a proto-fascist, but fascists as well as communists have contrived to exploit a debate that should be taken seriously: the role of art in society. Should it be more than art for art's sake? Should it have social relevance? Should it reflect regional or national traditions? Must it appeal to a large number of people?

At the same time as the 1937 exhibition

of German Art for All, Hitler's cultural commissars staged another show, of the alternative kind of art, what the Nazis called `entartete Kunst', degenerate art. More than two million people came to see this exhibition, which passed through several major German cities. The works of more than a hundred 'Jewish' and 'Bol- shevist' artists were held up as targets for popular ridicule and indignation. Like the authors whose books were burnt by Nazi students in 1933, the degenerate artists have mostly retained their high reputa- tions. Indeed, to be excoriated by Hitler's Propaganda Ministry was almost a guaran- tee of high quality: Kandinsky, Kokos- chka, Grosz, Dix, Beckmann, Klee, Ernst and Mondrian — they were all there to be spat at.

So to see their works now, in the oversized halls of the former Haus der Deutschen Kunst, is a form of revenge; they have won, Hitler's genre painters have lost. And yet, to view them there, dwarfed in Troost's building, is still a melancholy experience, for they simply don't fit. The atmosphere of the old Temple of Art drains these anarchic, angry, colourful, eccentric works of their vitality.

It would have been better, in a way, to have left the building empty, as a monu- ment to a period that took life away from art and put bombast and sentimentality in its place. This is not to say that avant-garde or modernist art is the only art of value, or that the debate about the social signifi- cance of art is over. There is a place for genre painting and popular (not populist) art. Even in a secular age, there is still room for religious art too. You don't have to be a Catholic to appreciate the beauty of a 15th-century Italian Madonna, or a Buddhist to enjoy a Tibetan scroll, or even a communist to like early Cuban film posters. But among the many criteria for a thing of beauty, one is indispensable: it must be true to itself; it cannot ring false. It is the falseness, even the aesthetic deceit, that makes Hitlerian, or Stalinist, or Maoist art so unbearable. That is what the museum in Munich cannot let you forget.

Previous page

Previous page