Why are his churches so empty?

Gregory Martin

PETER SAENREDAM: THE PAINTER AND HIS TIME by Gary Schwartz and Marten Jan Bok Thames & Hudson, £38, pp.356 In the late 1930s, on the basis of an analysis of a portrait of him drawn by his friend soon to be famous architect Jacop van Campen, Peter Saenredam was di- agnosed a hunchback. The character traits then associated with those thus handicap- ped, manifesting themselves in particular in a love of solitude, were thought to account for his meticulous renderings of empty or near empty churches. Indeed Saenredam's works are often noteworthy for the absence of purposeful human activ- ity and contrast with the established tradi- tion of depicting such interiors in the Netherlands and with the work of contem- poraries. Now, thanks to this biography, hand- somely illustrated but by no means satis- fying in its layout or in its intellectual structure, a different portrait emerges of this notable artist. His father was a gifted engraver, and his family ties with adminis- trators and members of the Reformed Church made available a network of con- tacts and friendships when he moved from his native Assendelft to Haarlem as an apprentice in 1612.

The possessor of a private income, stemming chiefly from inherited shares in the Dutch East India Company, his wide literary tastes are known as a result of the discovery not so long ago of a sale cata- logue of his library. Saenredam was to play an active role in the Haarlem guild of St Luke in the 1630s until his unhappy period as Dean in 1642. Then he strove at 40 board meetings unsuccessfully to resolve the feud between the guild allied with art dealers and a group of artists, among whom was Frans Hals, who wanted the freedom to offer at auction paintings from their studios.

By 1642 Saenredam had accumulated a stock of architectural sketches on which he was chiefly to rely for the rest of his career. What was new in his art as draughtsman

stemmed from an attitude similar perhaps to that which had provoked Prins Maurits — the stadtholder and inventor of military drill — to complain that artists relied too much on 'sight and guessing'. In Saenre- dam's case the catalyst was probably the example of the little known Pieter Wils, whose ground plan of St Bavo's, Haarlem, 'serviceable for those who wish to depict the same in perspective . . .', was pub- lished in a book to which Saenredam had also contributed. It appeared in 1628, the year Saenredam decided to specialise.

He was to supplement the skill of a surveyor at making measurements with a mastery of perspective. Thus there was to be no guesswork in the calculated contri- vances of pillars, arches, paved floors and vaulted ceilings in the so called 'construc- tion drawings'. These were made from the sketches as modellos, the tracings of which on to panel were then worked up in paint.

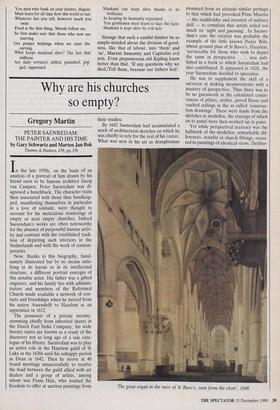

Yet while perspectival accuracy was the hallmark of the modellos, remarkable dif- ferences, notably in church fittings, occur- red in paintings of identical views. Deliber- °The great organ in the nave of St Bavo's, seen from the choir', 1648 ate intentions appeared in others, most notoriously in the 1846 view of the choir of St Janskerk, Bois le Duc, in which an altarpiece was depicted to replace that removed by the departing catholic clergy after the capture of the city by the States Army in 1629.

For all the authors' reliance on archival research, in particular into genealogies, inventories and records of sales, they cannot always come up with confident contexts. What they must have yearned for are the artist's account books and corres- pondence; in fact only a copy of one letter remains (as it happens about one of his most ambitious works, the Interior of St Bavo's, now at Edinburgh), while there is only one record of payment (for the one picture by him which has never changed hands, the view of the old Amsterdam Town Hall, on loan to the Rijksmuseum).

Instead, what the reader now has in sometimes ugly English is a mass of often discursive information about Saenredam's extended family and social network and about entities attached to various chur- ches. These reveal some bewildering com- plexities as the Reformed Church grappled to control the hearts and minds of the Dutch.

The consequent lack of focus of the new information is regretted, but the authors hope that their application of the concerns of sociology, in which works of art are regarded as 'signals', will provide a 'stimu- lus towards the construction of an historic- al framework for the study of Netherland- ish art'. Meanwhile, until such new facts as are discovered in the archives can be presented and interpreted in a more cohe- rent manner, it is hoped that they are only relayed in learned journals, as the general reader is more likely to be bemused than enlightened by them.

Previous page

Previous page