GRAND TOUR OPERATORS

Robert Taylor says the Blairs have

revived the old idea of what a prime minister's holiday should be

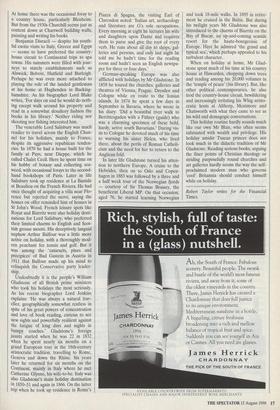

MR BLAIR, luxuriating en famine in Prince Girolamo Strozzi's palatial 50-room Renaissance villa in Tuscany before mov- ing on to an equally salubrious establish- ment in France, has revived the grand aristocratic style of British prime ministers in the last century when taking their long holidays at home and abroad.

Mr Blair's holiday preferences look more lavishly demanding than those of his recent predecessors. Labour prime minis- ters were particularly modest. Jim Callaghan liked to spend his time off down on his Sussex farm, while Harold Wilson was content to take his annual family holi- days in a three-bedroom bungalow he bought in the Scilly Isles. Attlee and his family were even more restrained. When leading Labour in opposition in the late 1930s they spent their holidays in boarding-houses at Weymouth and Seaton. The only foreign holidays recorded by the Attlees were to Ireland, Norway and France, where his wife Vi did the driving in their Morris Minor. For Ramsay Mac- Donald, leisure time mostly meant moping about in his home at Lossiemouth on the Moray Firth where he was born. That workaholic Margaret Thatcher tended to squeeze in a week and little more, mainly as a guest with husband Denis in the Swiss home near ZUrich of the former Conserva- tive MP Sir Douglas Glover. John and Norma Major were hardly more dashing, with short villa holidays mainly in the homes of friends in Spain.

Mr Blair's grand idea of a summer holi- day seems much more in the tradition of earlier prime ministers from the age when parliament was in session for less than half the year. Lloyd George, however, usually went on holiday without his wife. Margaret disliked the continent of Europe even more than England. While she stayed at home in Criccieth, north Wales, her rest- less husband often motored around France with his cronies, admiring the local peas- ant girls and talking politics. Later in life he used to enjoy the sybaritic life on the French Riviera, though it is doubtful whether his mind ever strayed far from sex and politics. Winston Churchill also seems to have spent many holidays away from his beloved Clementine, although he did not have a roving eye. In later life he enjoyed holidaying in Marrakech, Morocco, on Cap d'Ail as a guest of Lord Beaverbrook, and in Monte Carlo with Aristotle Onassis.

`Ciao, darling – we must make luvvy sometime.' At home there was the occasional foray to a country house, particularly Blenheim. But from the 1930s Churchill seems just as content down at Chartwell building walls, painting and writing his books.

Benjamin Disraeli — despite his youth- ful exotic visits to Italy, Greece and Egypt — seems to have preferred the country- house circuit to Continental trips to spa towns. His summers were filled with jour- neys to stately establishments such as Alnwick, Belvoir, Hatfield and Burleigh. Perhaps he was even more attached to playing the role of the landed gentleman at his home at Hughenden in Bucking- hamshire. As his biographer Lord Blake writes, 'For days on end he would do noth- ing except walk around his property and read in a somewhat desultory fashion the books in his library.' Neither riding nor shooting nor fishing interested him.

The venerable Lord Salisbury was much readier to travel across the English Chan- nel for his holidays, mainly to France, despite its aggressive republican tenden- cies. In 1870 he had a house built for the family at Puys, near Dieppe, which he called Chalet Cecil. Here he spent time on his hobby of botany and collecting sea- weed, with occasional forays to the second- hand bookshops of Paris. Later in life Salisbury took up residence at La Bastide at Beaulieu on the French Riviera. He had once thought of acquiring a villa near Flo- rence but rejected the move, saying the homes on offer reminded him of houses in St John's Wood. French leisure spots like Royat and Biarritz were also holiday desti- nations for Lord Salisbury, who preferred their limited charms to English and Scot- tish grouse moors. His deceptively languid nephew Arthur Balfour was a little more active on holiday, with a thoroughly mod- ern penchant for tennis and golf. But it was among the 'cataracts, pines and precipices' of Bad Gastein in Austria in 1911 that Balfour made up his mind to relinquish the Conservative party leader- ship.

Undoubtedly it is the people's William Gladstone of all British prime ministers who took his holidays the most seriously. As his recent biographer Lord Jenkins explains: 'He was always a natural trav- eller, geographically somewhat restless in spite of his great powers of concentration and love of book reading, curious to see new sights and powerfully resilient against the fatigue of long days and nights in bumpy coaches.' Gladstone's foreign jaunts started when he was 22 in 1832 when he spent nearly six months on a grand European tour in the 18th-century aristocratic tradition, travelling to Rome, Geneva and down the Rhine. Six years later he returned for six months on the Continent, mainly in Italy where he met Catherine Glynne, his wife-to-be. Italy was also Gladstone's main holiday destination in 1850-51 and again in 1866. On the latter trip when he took up residence in Rome's Piazza di Spagna, the visiting Earl of Clarendon noted: 'Italian art, archaeology and literature are G's sole occupations. Every morning at eight he lectures his wife and daughters upon Dante and requires them to parse and give the root of every verb. He runs about all day to shops, gal- leries and persons, and only last night he told me he hadn't time for the reading room and hadn't seen an English newspa- per for three or four days.'

German-speaking Europe was also afflicted with holidays by Mr Gladstone. In 1858 he toured the churches, galleries and theatres of Vienna, Prague, Dresden and Cologne while en route to the Ionian islands. In 1874 he spent a few days in September in Bavaria, where he wrote in his diary: 'Did a beautiful river walk to Berchtesgaden with a Fiihrer (guide) who was a charming specimen of these bold, hardy, active south Bavarians.' During vis- its to Cologne he devoted much of his time to warning his sister Helen, who lived there, about the perils of Roman Catholi- cism and the need for her to return to the Anglican fold.

In later life Gladstone turned his atten- tion to northern Europe. A cruise to the Hebrides, then on to Oslo and Copen- hagen in 1883 was followed by a three and a half week tour of the Norwegian fjords — courtesy of Sir Thomas Brassey, the beneficent Liberal MP. On that occasion, aged 76, he started learning Norwegian and took 18-mile walks. In 1895 in retire- ment he cruised in the Baltic. But during his twilight years Mr Gladstone was also introduced to the charms of Biarritz on the Bay of Biscay, an up-and-coming seaside resort for the haute-bourgeoisie of Europe. Here he admired 'the grand and typical sea', which perhaps appealed to his turbulent character.

When on holiday at home, Mr Glad- stone spent much of his time at his country house at Hawarden, chopping down trees and reading among his 20,000 volumes in the 'temple of peace' (his library). But, like other political contemporaries, he also trod the country-house circuit, bewildering and increasingly irritating his Whig aristo- cratic hosts at Althorp, Mentmore and Chatsworth with what they came to see as his wild and demagogic conversations.

This holiday routine hardly sounds much like our own Mr Blair, who often seems infatuated with wealth and privilege. His holiday amidst Tuscan princes does not look much in the didactic tradition of Mr Gladstone. Reading serious books, arguing the finer points of Christian theology or striding purposefully round churches and art galleries hardly seems the way the self- proclaimed modern man who governs `cool' Britannia should conduct himself while on holiday.

Robert Taylor writes for the Financial Times.

Previous page

Previous page