`WHAT IF JAM

A SNOB?'

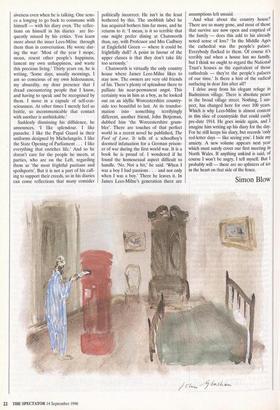

Profile: James Lees-Milne, who lives among hunting folk, but is the last of the aesthetes

IT WAS appropriate that my first meeting with James Lees-Milne — elder statesman of the country-house whose latest book has just been published (Fourteen Friends, John Murray) — should have been in one. We were both staying at Vaynol Park, North Wales, the seat of that sadly missed raconteur and specialist in royal yarns, Sir Michael Duff. It was at Vaynol that I realised that a sound reason for the contin- uing existence of the lived-in country house was its profound influence on the anecdote. The pointed anecdote breeds nowhere so well as in the country house. And here were two anecdotalists indulging in this most civilising of pastimes. Tall and ramrod-backed, Michael Duff sat at the head of the table telling anecdote after anecdote about his godmother, Queen Mary. There was the story of the poor relation who had a priceless icon snapped shut in her face when she had muttered to her royal cousin that this treasure had once belonged to her father. Then, in his meticulously clipped and measured voice, Duff said, 'Did you know that the King would make Queen Mary join the beaters at Sandringham? He would shout at her in guttural tones, "May, r-a-a-ttle your brol- lie! R-a-a-ttle your brollie!" ' Now James Lees-Milne slipped one in too. A kind of honorary aunt of his, Puss Milnes-Gaskell, had once had her arm firmly trodden on by Queen Mary. Puss, a lady-in-waiting, was with the Queen when her Daimler had toppled over. The Queen at once got out, her toque and parasol immaculately in place, having used poor Puss Milnes-Gaskell's arm as her spring- board. For the next two weeks Puss had to answer letters of condolence written expressly to Queen Mary — who wasn't injured one bit — with an arm excruciat- ingly dented by the Queen's foot.

Soon after my visit, I started reading James Lees-Milne's diaries. The portraits I found there — brought alive by anecdote — were of cantankerous and eccentric country-house owners, of a non-toiling society world where a superb self-confi- dence reigned, the whole threaded by Lees-Milne's own peregrinations from country house to country house. But Lees- Milne often went as a toiler, for he had a job to do. In 1936 he had become one of the four-strong team that was to halt a vandalistic laying waste of the noble state- ly homes. The National Trust's new Coun- try Houses Committee sent forth Lees-Milne as ambassador to explain to owners — grimly cast down by death duties and depression — that the Trust was now here as their potential rescuer. And so Lees-Milne found himself an on- the-scene witness to the salvaging of Lloyd George's detested 'privileged' society. The s'tuation, aggravated again by war, tapped Lees-Milne's natural talent as a diarist. Almost as essential as the many houses he rescued — and families too — are his can- did reports on these people in peril. He began his diary in 1942, as an honest record of the turmoil, with never a thought to eventual publication.

But when the diaries first appeared 40 years later, he got into trouble for being far too blunt. There were some who were upset to read of their weaknesses — possi- bly never pointed out to them before and in anger purposely missed a possible compliment on the next few pages. James Lees-Milne shows true distress at causing

hurt, and as a result he is self-deprecatingly dismissive of these important journals: 'I'm not in the least proud of them. I suppose I shouldn't have published them. But I did. Is that insensitivity? I don't know. Perhaps we're all insensitive to an extent.' I suggest to him that writing doesn't succeed unless the writer has splinters of ice in the heart. He ponders this: 'You mean as the Duke of Windsor said of Queen Mary, "She had ice in her veins" ?' There is a side to him that is startlingly innocent. He doesn't appear to have thought about it in this way — or imag- ines that anyone could have been upset.

And yet when he allows himself to be drawn on the diary subject, he talks with complete professionalism: 'It's terribly important not to fudge diaries. I've never added anything. All I ever do is edit for grammar and style, because often I've writ- ten them quickly when I've been, say, on a train.' He very much admires the diaries of William Beckford and, more recently, of his friend Anthony Powell. 'Oh, waspish, won- derfully waspish,' he remarks. 'Of course a diary must be candid. It's of no interest if it isn't.' But he remains affected by what he saw in those war years of the country-house owners, and in particular the elderly ladies struggling alone down their long passages, with no help and in the blackout.

Censorious reviewers have called James Lees-Milne a snob. 'What if I am a snob or an elitist? Does it honestly matter?' he ventures. In fact such accusations make him a little angry, because they completely miss his point. These attacks are as well reasoned as asking Proust to rewrite his novel leaving out all titles. The English upper class — through their clannishness so unknowable to the majority — are best conveyed by one who understands their rules. Lees-Milne knows every nuance, which is why his diary vignettes of those distant days carry authority. Take an exam- ple. While negotiating for Stourhead, he dines with Sir Henry and Lady Hoare. In spite of war, they eat well — a dinner of soup, whiting, pheasant, apple pie and dessert. Lady Hoare — `tall, ugly and 82' but 'an absolute treasure, and unique' announces, The Duchess of Somerset at Maiden Bradley has to do all her own cooking.' This is followed by, 'Don't you find the food better in this war than the last?' Lees-Milne remembers only the ran- cid margarine at his preparatory school. `Oh!' replies Lady Hoare. 'You were lucky. We were reduced to eating rats.' Sir Henry — 'an astonishing 19th-century John Bull, hobbling on two sticks' — interrupts, 'No, no, Alda. You keep getting your wars wrong. That was when you were in Paris during the Commune.' An education at Eton and Magdalen, Oxford, put Lees-Milne in easy familiarity with his upper-class subject matter. He came, anyway, from a comfortable back- ground, but quickly announces, 'I've got no blue blood in my veins whatsoever. I'm of yeoman stock.' The Lees side, he explains, were 'landed eventually' and the Milne side were trade — cotton mills. The family was officially upgraded to 'Gentleman' around 1750, and a little later (c. 1810) they were allowed to be 'Esquire'. He is amused by these small class distinctions. He wonders who would have ruled on the upping of the status. 'The College of Her- alds, do you think?'

But when James came into the family in 1908, there was a manor house in Worces- tershire surrounded by some land which his father farmed. The aesthete in James start- ed early, and this left him without much conversation with his father. Allowing the public to ramble round other people's homes Lees-Milne senior saw as socialism. He disapproved of the National Trust. But that Lees-Milne junior was to spend his life rescuing England's historic houses was in fact the result of the behaviour of some ignorant inmates at William Kent's very splendid Rousham Park in Oxfordshire. The house was let, and after dinner the drunken host let fly at the family portraits with a hunting whip. He also shot at the gar- den statues with a rifle. From then on the young James — shocked into silence by what he saw — planned to wage constant war against the Philistine.

It must seem strange, then, that this aes- thete should live in the village of Bad- minton — a place associated primarily with robust hunting and the three-day event. But Lees-Milne and his wife, Alvilde, were close friends of the late Duke of Beaufort's heirs, David and Caro- line Somerset, who encouraged them to settle in an enchanting 17th-century stone house close to the gates of the big house. There, on occasion, they witnessed the fox-hunting wrath of the late Duke, fitting- ly nicknamed Master: 'What's the point of the Lees-Milnes? They don't hunt. They don't shoot. What use are they?'

Since Alvilde's death two years ago, Lees-Milne has lived alone there. They were both independent people, but the marriage lasted over 30 years. Alvilde broke through a shyness by making direct — and sometimes too direct — comments. 'I see. Mutton dressed as lamb,' she said to an octogenarian dowager making an appearance at a ball. She gained a reputa- tion for being as outspoken as he is reti- cent. But she had a distinct talent for kindness, dressed stylishly, and was widely respected as a gardener. One of her garden layouts, for instance, was for Mick Jagger in France. The gardening was a result of James introducing her to Vita Sackville- West. For James Lees-Milne not enough good can be said of Vita. 'There was noth- ing you couldn't discuss with her. She was absolutely tolerant — no barriers whatso- ever. Of course she was a feminist. She hated being Lady Nicolson because she hadn't earned that — she was Vita Sackville-West.'

Lees-Milne has known almost everybody. In the case of the Nicolsons, he has been Harold's biographer, while a spate of books on architecture and people have poured out at two-yearly intervals. The diaries indi- cate a hectic social life, but he claims that he is not a mixer and that he's hopeless at parties. It is possible to discern this reclu- siveness even when he is talking. One sens- es a longing to go back to commune with himself — with his diary even. The reflec- tions on himself in his diaries are fre- quently missed by his critics. You learn more about the inner Lees-Milne through them than in conversation. He wrote dur- ing the war: 'Most of the year I mope, moan, resent other people's happiness, lament my own unhappiness, and waste this precious living.' Thirty years on, he is writing, 'Some days, usually mornings, I am so conscious of my own hideousness, my absurdity, my dour presence that I dread encountering people that I know, and having to speak and be recognised by them. I move in a capsule of self-con- sciousness. At other times I merely feel so brittle, so incommunicable that contact with another is unthinkable.'

Suddenly dismissing his diffidence, he announces, 'I like splendour. I like panache. I like the Papal Guard in their uniforms designed by Michelangelo. I like the State Opening of Parliament . . . I like everything that enriches life.' And so he doesn't care for the people he meets, at parties, who are on the Left, regarding them as 'the most frightful puritans and spoilsports'. But it is not a part of his call- ing to support their creeds, so in his diaries can come reflections that many consider

politically incorrect. He isn't in the least bothered by this. The snobbish label he has acquired bothers him far more, and he returns to it: 'I mean, is it so terrible that one might prefer dining at Chatsworth than, say; with Professor and Mrs Cadbury at Englefield Green — where it could be frightfully dull? A point in favour of the upper classes is that they don't take life too seriously.'

Chatsworth is virtually the only country house where James Lees-Milne likes to stay now. The owners are very old friends of his. There's plenty of splendour there to palliate his near-permanent angst. This certainty was in him as a boy, as he looked out on an idyllic Worcestershire country- side too beautiful to last. At its transfor- mation into something terrifyingly different, another friend, John Betjeman, dubbed him 'the Worcestershire grum- bler'. There are touches of that perfect world in a recent novel he published, The Fool of Love. It tells of a schoolboy's doomed infatuation for a German prison- er of war during the first world war. It is a book he is proud of. I wondered if he found the homosexual aspect difficult to handle. 'No. Not a bit,' he said. 'When I was a boy I had passions . .. and not only when I was a boy.' There he leaves it. In James Lees-Milne's generation there are

assumptions left unsaid. And what about the country house? There are so many gone, and most of those that survive are now open and emptied of the family — does this add to his already noted sense of loss? 'In the Middle Ages the cathedral was the people's palace. Everybody flocked to them. Of course it's terribly sad when a house has no family, but I think we ought to regard the National Trust's houses as the equivalent of those cathedrals — they're the people's palaces of our time.' Is there a hint of the radical surfacing in dear Jim after all?

I drive away from his elegant refuge in Badminton village. There is absolute peace in the broad village street. Nothing, I sus- pect, has changed here for over 100 years. Which is why Lees-Milne is almost content in this slice of countryside that could easily pre-date 1914. He goes inside again, and I imagine him writing up his diary for the day. For he still keeps his diary, but records 'only red-letter days — like seeing you'. I hide my anxiety. A new volume appears next year which must surely cover our first meeting in North Wales. If anything unkind is said, of course I won't be angry, I tell myself. But I probably will — there are no splinters of ice in the heart on that side of the fence.

Simon Blow

Previous page

Previous page