Exhibitions 1

Grinling Gibbons (Victoria and Albert Museum, till 24 January)

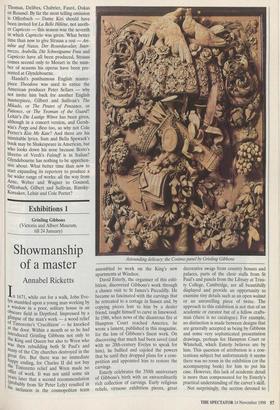

Showmanship of a master

Annabel Ricketts

In 1671, while out for a walk, John Eve- lyn stumbled upon a young man working by a window in a poor, solitary house in an obscure field in Deptford. Impressed by a glimpse of the man's work — a wood relief of Tintoretto's 'Crucifixion' — he knocked at the door. Within a month or so he had introduced Grinling Gibbons not only to the King and Queen but also to Wren who Was then rebuilding both St Paul's and many of the City churches destroyed in the great fire. But there was no immediate ilaPPY ending, for Charles II did not buy the Tintoretto relief and Wren made no offer of work. It was not until some six Years later that a second recommendation liobably from Sir Peter Lely) resulted in s Inclusion in the cosmopolitan team Astounding delicacy: the Cosimo panel by Grinling Gibbons assembled to work on the King's new apartments at Windsor.

David Esterly, the organiser of this exhi- bition, discovered Gibbons's work through a chance visit to St James's Piccadilly. He became so fascinated with the carvings that he retreated to a cottage in Sussex and, by copying pieces lent to him by a dealer friend, taught himself to carve in limewood. In 1986, when news of the disastrous fire at Hampton Court reached America, he wrote a lament, published in this magazine, for the loss of Gibbons's finest work. On discovering that much had been saved (and with no 20th-century Evelyn to speak for him), he bullied and cajoled the powers that be until they dropped plans for a com- petition and appointed him to restore the carvings.

Esterly celebrates the 350th anniversary of Gibbons's birth with an extraordinarily rich collection of carvings. Early religious reliefs, virtuoso exhibition pieces, great decorative swags from country houses and palaces, parts of the choir stalls from St Paul's and panels from the Library at Trini- ty College, Cambridge, are all beautifully displayed and provide an opportunity to examine tiny details such as an open walnut or an unravelling piece of twine. The approach to this exhibition is not that of an academic or curator but of a fellow crafts- man (there is no catalogue). For example, no distinction is made between designs that are generally accepted as being by Gibbons and some very sophisticated presentation drawings, perhaps for Hampton Court or Whitehall, which Esterly believes are by him. This question of attribution is a con- tentious subject but unfortunately it seems there was no room in the exhibition (or the accompanying book) for him to put his case. However, this lack of academic detail is more than compensated for by Esterly's practical understanding of the carver's skill.

Not surprisingly, the section devoted to Gibbons's techniques is particularly fasci- nating. The unique qualities of limewood are contrasted with the more intractable nature of oak which, before Gibbons's arrival, was the British woodcarver's pre- ferred medium. A vast array of (modern) chisels and gouges gives some idea of the tools needed to achieve such delicacy. There are also some unassuming little bits of rush. These absorb silica from the sand in which they grow and then deposit it in tiny beads on their stems forming an effec- tive precursor of sandpaper (which was not invented until the 19th century). Modern limewood boards are marked up to show how assistants would know what to carve, and photographs of dismantled works show how boards were superimposed to give greater depth and how tiny platforms were provided for fixing extra pieces. By includ- ing some of his limewood carving in the exhibition, Esterly demonstrates the startling paleness of freshly carved lime- wood. This emphasises the depredations suffered by much of Gibbons's work which, often in the name of preservation, has been coated in a variety of paints, varnishes and waxes, something that Esterly likens to painting Michelangelo's 'David' with dark- brown paint.

The exhibition is a brilliant demonstra- tion of Gibbons's craftsmanship, but it also shows his limitations. Illusionistic trickery was much valued in the 17th century, and a good example is the fashionable 'wood as lace' trick which so captivated Horace Walpole a century later (he supposedly wore Grinling Gibbons's wooden cravat for a day to fool his friends). But such trickery can begin to pall. The star of the show is the Cosimo panel, which Charles II pre- sented to the Grand Duke of Tuscany as a token of friendship in 1682. Here, the deli- cacy of the carving is astounding but the raison d'être for much of the work is dis- play itself. As a design it is pretty conven- tional: crowns, quivers of darts and standard references to art and music, topped with (of course) a huge canopy of lace and a pair of billing doves. Objects, it seems, were chosen expressly to display the craftsman's skill. Why else is there an unattached wing on the right-hand side? Why else does the chain of the medallion loop so inconsequentially around so many objects? Gibbons's strength was not as a designer but as a craftsman exploiting to its limits the possibilities of his chosen medi- um. But for all that, the Cosimo panel con- tains a surprise that cannot have been included as part of a virtuoso display. Almost completely hidden just above the quiver is a bleeding heart, only discovered by the Italian curator when the panel was being prepared for its journey to England.

This exhibition provides a unique chance to see Gibbons's work close up, beautifully lit and from angles that would usually be impossible. It shows how limited the tradi- tion of woodcarving was in Britain before Gibbons's arrival, and how great was his skill in conjuring the seemingly impossible from so intractable a material. Don't miss the chance to admire the showmanship of a master craftsman.

Previous page

Previous page