Did they or didn't they, or don't we care?

Raymond Carr

THE LETTERS OF ARTHUR BALFOUR AND LADY ELCHO edited by Jane Ridley and Clayre Percy Hamish Hamilton, £25, pp. 370 The fascination of this exchange of letters between A. J. Balfour, leader of the Conservative party in the Commons (1892- 1911) and prime minister (1902-6), and Lady Elcho, wife of Hugo Elcho, heir to the earldom of Wemyss, lies in the portrait it yields of aristocratic, social and political life between 1890 and the first world war. In particular, it illuminates that circle known to the envious excluded from it as the Souls. The Souls have attracted almost as much nostalgic brooding as the Blooms- bury group; but a group they were not. They were, in Balfour's words, a 'gang', a circle of friends who shared common tastes and met each other at the country-house parties to which Balfour was addicted and of which he was 'King Arthur' — spoiled and flattered by female admirers. What united them was their rejection of the circumambient philistinism of the English upper classes, typified in the Marlborough House set of the Prince of Wales and after- dinner conversation devoted to field sports and racing. 'I do not see', Balfour remarked, 'why I should break my neck because a dog chooses to run after a nasty smell'. As these letters make abundantly clear, Balfour's passion was golf, already on the way to becoming the British middle- class sport par excellence. They were intel- ligent but, apart from Curzon, the Lytteltons, the Wyndhams and Balfour himself, who had a lifelong philosophical interest in the nature of religious and sci- entific truth, they were not intellectuals. Intellectuals were co-opted into the charmed circle as prize exhibits from a wider world — the Webbs whose insistent seriousness struck a discordant note, Shaw, Wells, Barry. But the core was aristocratic — mostly but not exclusively Tories. Mar- got Tennant, who was to marry the Liberal Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, was neither aristocratic nor Tory; but she was outrageously amusing and very rich.

These letters show how the Souls were held together by hostesses with large houses and time on their hands. My mother-in-law, Mary Elcho's illegitimate daughter, told my bride and myself, on the eve of our wedding, 'Of course you will never have affairs because you won't be able to afford enough servants'. The Souls had both servants and affairs. While Mary Elcho was sleeping with Wilfred Scawen Blunt in the Egyptian desert — my mother- in-law was the result — her husband was consoling his dying mistress, the Duchess of Leinster, in Cannes; George Wyndham, Mary Elcho's brother, enjoyed a long and public affair with Gay Plymouth. Harry Cust was a notorious groper at dinner parties.

What was the nature of Balfour's relations with Mary Elcho? When Kenneth Young published his biography of Balfour in 1963 he used their correspondence, not merely to imply that their relationship was physical, but that Mary Elcho was a goose who pursued Balfour. So indignant were the Charteris fainily (my mother-in-law's copy of Young is plastered with angry marginalia, exposing some silly errors) that they withdrew the correspondence from the British Museum. It is now at Stanway, the family home whence so many of Mary Elcho's letters were written.

The letters in this book make it clear that Mary Elcho loved Balfour. Her arranged marriage to a philanderer whose gambling on the stock exchange threatened to ruin the family, left her emotionally starved. A letter on Valentine's Day 1905 shows that she would have preferred to many Balfour; other letters reveal a strong jealousy of the rival physical and intellectual charms of that lion-hunting hostess Lady Desbor- ough. It must be a fair assumption that, given encouragement from Balfour, she would have embarked on an affair, as she had with Blunt whom she neither loved nor admired as she did Balfour.

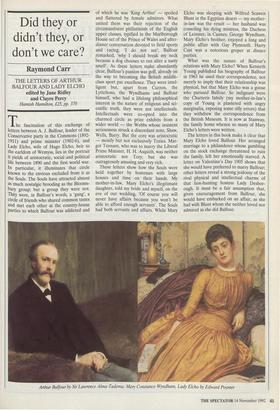

Arthur Balfour by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema; Mary Constance Wyndham, Lady Elcho by Edward Poynter But Balfour gave no such encourage- ment. His letters give an impression of `reculer pour mieux reculer'. In the coded language of the time, Mary's letters hint at a physical relationship established by a `change of gear' in 1887; her most explicit letter she asks Balfour to destroy. 'Is she', she writes of Lady Desborough, 'to be my substitute in every particular?' There are mysterious references to 'a good smacking,' hints at the 'liberal education' of a 'poor young girl' that left 'no regions of her little body unexplored'. But Balfour never responds to these messages. That he loved her in his fashion there can be no doubt: she was a warn, immensely lovable person and, as her letters during the war show, she mercifully lacked the gushing strain that disfigures so much of the letters of that time. But she complains of Balfour's `inertia'. Max Egremont argues in his biography of Balfour that he was marked by 'a fear of emotion rather than an absence of feeling or coldness of spirit': the editors of this collection talk of Balfour's `pent up and twisted sexuality'. One simple solution may be that he was impotent and that the 'gear change' of 1887 never got into top. But does it really matter whether or not they went to bed together? These letters are a moving tribute to a friendship that was essential to both parties. 'Although you have loved me little,' Mary Elcho writes, 'you have loved me long'.

Do these letters tell us anything about Balfour as a politician that we do not know already? They are not in the same class as Asquith's indiscreet correspondence with Venetia Stanley. This is not surprising: Balfour could give a philosophical lecture or a parliamentary speech from the prover- bial back of an envelope but confessed that he hated letter-writing 'like the devil', and Mary Elcho was not a political being. They wrote to each other about their friends' goings-on. The letters reveal Balfour's somewhat distant attitude to the 'mill' of political life — Mary Elcho laments his refusal to read the press. But they give little impression of his tenacity and tough- ness, for instance in driving his Irish legislation and the Education Bill of 1902 through Parliament. He may have been propelled into politics by his uncle, Lord Salisbury, whose Hobbesian pessimism he shared. He professed to regard himself as utterly unsuited to the kind of work into which I have been dragged'; but as he writes, he stuck at the 'mill' as leader of his Party for a record 25 years. Politics was at the outset a civilised game: Balfour dines with Asquith and shares a cab with him to the House of Commons, joking whether it is moral to attack a man whose champagne he has just consumed. But things get rough when the Conservative party splits over tar- iff reform, a self-inflicted wound that, as Douglas Hurd reminded the faithful at Brighton, only serves to let in the opposi- tion. The letters reflect Balfour's efforts to keep his party in some semblance of unity by an ambiguous compromise that satisfied no one.

Things got even rougher with the struggle for the Parliament Act to limit the powers of the House of Lords. Balfour cannot forgive Asquith and the King's secretary Lord Knollys for persuading an inexperienced king to promise to create enough peers to swamp the 'ditcher's' resis- tance. It was, he wrote, 'a shocking scan- dal'. Margot Asquith is accused of deliberate deceit; the Cecils have become lunatics'. Politics had become 'unusually odious'.

It is the triumph of the editors that they have created from a somewhat disjointed correspondence a satisfying whole. The interpolated explanatory passages set the letters in context; the footnotes are a sheer joy. It is the editors' skills that have made this correspondence fascinating reading. Historians should be duly grateful.

Previous page

Previous page