ENOCH THE UNEXPECTED

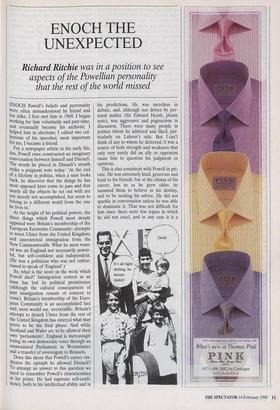

Richard Ritchie was in a position to see

aspects of the Powellian personality that the rest of the world missed

ENOCH Powell's beliefs and personality were often misunderstood by friend and foe alike. I first met him in 1969. I began working for him voluntarily and part-time, and eventually became his archivist; I helped him in elections; I edited two col- lections of his speeches; most important for me, I became a friend.

For a newspaper article in the early Six- ties, Powell once constructed an imaginary Conversation between himself and Disraeli. The words he placed in Disraeli's mouth strike a poignant note today: 'At the end of a lifetime in politics, when a man looks back, he discovers that the things he has most opposed have come to pass and that nearly all the objects he set out with are not merely not accomplished, but seem to belong to a different world from the one he lives in.'

At the height of his political powers, the three things which Powell most deeply opposed were Britain's membership of the European Economic Community; attempts to wrest Ulster from the United Kingdom; and unrestricted immigration from the New Commonwealth. What he most want- ed was an England not necessarily power- ful, but self-confident and independent. (He was a politician who was not embar- rassed to speak of 'England') So, what is the score in the week which Powell died? Immigration control as an issue has lost its political prominence (although the cultural consequences of past immigration remain of concern to some). Britain's membership of the Euro- pean Community is an accomplished fact and, most would say, irreversible. Britain's attempt to detach Ulster from the rest of the United Kingdom has entered what may prove to be the final phase. And while Scotland and Wales are to be allowed their own 'parliaments', England is increasingly losing its own democratic voice through an emasculated Parliament in Westminster and a transfer of sovereignty to Brussels.

Does this mean that Powell's career vin- dicates the epitaph he allowed Disraeli? To attempt an answer to this question we need to remember Powell's characteristics in his prime. He had supreme self-confi- dence, both in his intellectual ability and in his predictions. He was merciless in debate, and, although not driven by per- sonal malice (Sir Edward Heath, please note), was aggressive and pugnacious in discussion. There were many people in politics whom he admired and liked, par- ticularly on Labour's side. But I can't think of any to whom he deferred; it was a source of both strength and weakness that only very rarely did an ally or opponent cause him to question his judgment or opinions.

This is also consistent with Powell in pri- vate. He was extremely kind, generous and loyal to his friends; but at the climax of his career, less so as he grew older, he assumed them to believe in his destiny, and to be seeking his advice. He did not sparkle in conversation unless he was able to dominate it. That was not difficult for him since there were few topics in which he did not excel, and in any case it is a characteristic which he holds in common with many great men. But it was left to his daughters to chant at him gleefully, `Me, me, me' when he carried his dominance too far.

So, there is this paradox. At the time when Powell was most confident of his opinions, and of his ability to shape events whether in terms of blocking legislation such as the reform of the House of Lords, or winning (and losing) elections for the Conservative party, subconsciously he envisaged ultimate political failure. But I think he got it the wrong way round. As one can now see, he exaggerated his pow- ers at their zenith, but underestimated the sea-change he brought about in British politics.

Certainly, his ideas were more main- stream at his death than when he was in Parliament. On economic policy, for exam- ple, his prescriptions became official Con- servative (and now Labour) policy. Perversely, his detachment from economic issues grew progressively as his remedies gained acceptance. It is a key to part of his character that, once his views became con- ventional, he tended to lose interest in them. Thus, towards the end of his life he showed signs of flirting with protectionism — partly, I suspect, in order to swim against the tide, and partly to underline a country's right to decide (albeit unwisely) its terms of trade unilaterally.

This change of mind was never devel- oped or publicised. It began as a reaction against a consequence of EU membership: the United Kingdom no longer having a trade policy of its own. In the late Seven- ties, for example, Powell argued in a speech that 'it will be better for our ego though not devoid of economic disadvan- tage — to slap a protective tariff on this or that class of beastly foreign articles, so that we can enjoy our own dearer and inferior products undisturbed . . . it doesn't make sense but it's patriotic.' But I have a feel- ing that he began to think it might make sense as well, particularly if there were a democratic will supporting it. For exam- ple, during one of the habitual coal crises of recent years he told me that he had no objection to supporting the coal industry, either through the restriction of cheap coal imports or subsidy, if it were the country's wish to preserve local coal com- munities.

Obviously, in taking this attitude, he was always on the look-out for the opportunity to illustrate what 'loss of sovereignty' meant in practice, but there was also an element of a change of heart in this approach — that perhaps the 'market' ought not necessarily to be sovereign in all matters. Ironically, just as the Conserva- tive party was becoming more economical- ly liberal, he appeared to be becoming even more of a 'Tory' and more anxious for the social fabric of the nation than for the undiluted play of market forces.

But this was a symptom of a deeper truth. I doubt whether, even in the Sixties and when Tory interventionism was at its height, Powell ever felt as strongly about economic questions as he did about issues affecting Parliament and this country's sense of nationhood. This is why both immigration and 'Europe' (how he hated that shorthand expression!), followed later by Ulster, became for him the supreme issues. These are the reasons why, on his own criteria, some will today judge his career to have been a failure.

His views on immigration, in particular, account for the hostility which he aroused in so many quarters. Some argue that he attempted to incite racial hatred, and failed. Others, that he chose immigration as an issue to build up a power base and attract popularity. But there is an alterna- tive explanation. He forced both political parties to accept reluctantly the need for immigration controls, and he gave assur- ance to millions of British voters that their fears and anxieties had a champion in Par- liament. To some this was demagoguery; to others, it is one reason why Britain has managed to escape so far the most extreme forms of racial prejudice and unrest.

Powell was never greatly interested in formulating detailed policies — and cer- tainly not in Opposition. He believed that if the intellectual foundations were secure and principled the policies would look after themselves. It was his reasoning and intel- lectual approach which captured the imagi- nation. He was the Tory intellectual who came to the rescue when socialism seemed invincible. He was classless, impossible to compartmentalise, and undefeatable in debate. He moulded a new political gener- ation, and both Mrs Thatcher and New Labour owe their success to the changed intellectual climate for which he was largely responsible. A Labour opponent once described 'Powellism' as a virus. He retort- ed, 'Yes. I am the virus that kills socialism.'

I once asked Powell whether he was encouraged by a growing hostility among young Conservative politicians to Britain's membership of the European Community. He replied, 'It was always a generation which did not remember those who had defended and developed the characteristic constitutional rights of the United King- dom in the past who have done the same in their own time.'

I believe he died confident that this will happen. But then Powell was always the eternal optimist. If the saints in Heaven or the souls in Purgatory retain any interest in what happens on earth, surely the first thing Powell will wish to discover — apart from why, when and by whom the Gospels were written — is whether the European Union is a 'blip' in England's history, or the beginning of the end of nationhood. And if so, does it matter? Whatever the answer, I hope he has at last achieved the peace of mind which makes all such questions tran- sitory and unimportant.

Previous page

Previous page