ARTS

Singing in jubilation

Michael Marshall meditates on the music and mystery of Christmas There was 'no room in the inn', you will recall. But then 'accommodating' the infi- nite within the finite dimensions of a restricted universe has always presented problems and not least for communicators. Little wonder, therefore, that when the vocabulary of the Infinite stepped into his- tory — 'the Word became flesh,' as the the- ologians prefer to express it — we found ourselves pushed to the edges of our resources and at some difficulty to find adequate accommodation, in any sense of that word. Little wonder that there was no room for Him in the inn, that first Christ- mas.

So, throughout the centuries, all artists have struggled to 'accommodate' the infi- nite within the finite, whether it be the artist who finds the colours of the palette all too restrictive, or even the musician who at least has a somewhat richer 'vocabulary' to draw upon. It was Augustine of Hippo, who still enjoys a reputation out of all pro- portion to the size of his little north African diocese, who exhorted his tongue- tied and somewhat parochial flock with their limited resources: 'Language is too poor to speak of God ... yet you do not like to be silent. What is left for you but to sing in jubilation?'

And that, of course, is what traditionally we believe the angels did that first Christ- mas Eve to herald the arrival of the Christ Child, though admittedly St Luke does not actually tell us that they sang. One thing is certain: the shepherds for whom the 'con- cert' was specifically arranged would never have responded to a bald prosaic theologi- cal lecture, however articulate or 'user- friendly' it might have been.

So, 'suddenly,' scripture records, 'there was with the angel a multitude of the heav- enly host, praising God and saying, "Glory to God in the highest ..." Clearly, scrip- ture records 'saying' but you might want to bet a modest dollar to a dime that the 'host', so cooly referred to in the canon of scripture, was nothing less and something infinitely greater than a choir or even a great chorus, and furthermore that they burst into jubilant song, in comparison with which even the best of Bach's Christmas Oratorio, or Handel's Messiah constitute but faint echoes. Charles Ives was right when he asserted, 'Music is one of the ways God has of beating in on man.'

We hear a great deal nowadays about the two sides of the brain, for it would seem, after all, that there really are two sides to all of us. The left hand side of the brain drives the right hand and is the receptor of all that information technology with which we are plagued, while the right hand side drives the left hand which is the poetic, intuitive, imaginative side to all of us. Part of the predicament of our age is apparently that it has concentrated (literally) on the left hand side of the brain for so long that we are seriously in danger of getting out of touch with the more reflective side of our natures.

It was that same Augustine referred to above to whom the memorable words are frequently attributed: `To sing is to pray twice.' Perhaps if he had lived in our post- modern age he might have said, `To sing is to pray with both sides of the brain.' For failing the existence of a universal language — such as Latin purported to be in the Middle Ages — it could be that music is the nearest we shall come on earth to a universal language — certainly one which can communicate the deep and significant realities and experiences of our finite world.

For what is certain is that we all need a language for mystery — not only the the- ologians and the poets but also the scien- tists with their new cosmology, so much less cut and dried than the triumphalistic claims of an earlier scientism. Few scien- tists today would speak of a closed and mechanistic universe. In place of a neatly formulated, predictable and ordered uni- verse, many now prefer to speak of what is fondly termed the 'chaos theory' in which mystery is no admission of failure to com- prehend, but rather perceived as a higher form of knowledge. So it was Einstein as long ago as 1932, while addressing the Ger- man League of Human Rights, who was not ashamed to assert, 'The most beautiful and deepest experience a man can have is the sense of the mysterious. It is the under- lying principle of religion as well as of all serious endeavours in art and science.' It would seem that both scientist as well as artist can claim in our age that there really is more to the universe and to the world around us than meets the eye — or the ear.

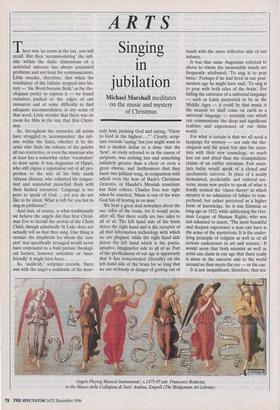

It is not insignificant, therefore, that tra- Angels Playing Musical Instruments', c.1475-97 attr. Francesco Botticini, in the Museo della Collegiata di Sant' Andrea, Empoli (The Bridgeman Art Library) ditionally for 2,000 years Christians have begun their worship and liturgy by drawing upon that song of the angels 'sung' at the first Christmas: 'Glory to God in the high- est.' The very words have inspired com- posers to strain to the limits the excellence of their medium and craft.

'Why was I created?' asks the Scottish Catechism. And the reply: 'In order to wor- ship God and to enjoy Him for ever.' Or, if you are suspicious of catechisms in any form, then perhaps the testimony of the psychiatrist fur Peter Shaffer's play Equus will serve to assert the same claim: 'If you don't worship, you'll shrink, it's as brutal as that.'

For the Christmas scene whether expressed through visual art, poetry or music was first addressed to us in pictures and language inviting our worship and self- transcendence. The vision transcended the world of everyday life, not in order that we might escape from the pains of our world to a different world, but rather that we might be given a glimpse and even a vision of the same, tired old world seen from a new perspective and in a new light — whether it be the light that streamed from the star which drew the Wise Men to the Christ Child; or the light from the skies when the host of angels broke through with their message of hope and glory; or the light from that Child in the manager — the Light of the world — from whom all other light takes its origin and is but a reflection.

So whether it is the paintings on many of our Christmas cards or the music of carols, the mass or oratorios, all alike are straining to capture, reflect and echo something of the truth of the Christmas message. 'The artist — the real artist,' claims Bernard Levin, 'is not painting a milk jug, or sun- flowers, or the Crucifixion,' or, you might add, the nativity. 'He is painting truth.'

Yet can the same claims be made for the medium of music with its wordless vocabu- lary? Surely it can. All great music (whether specifically religious or not) 'points the way to our human understand- ing of our human duty', concludes Bernard Levin, 'the duty to be transformed, to rise from darkness into light, to pursue the will o' the wisp of integration and completeness until it turns out to be no will o' the wisp, but the shining light of eternal truth'. In a word — worship.

Nevertheless, such glorious words how- ever eloquent might have fallen on deaf ears for those shepherds. Little wonder then that an angelic choir and skilled musi- cians were hired, so to speak, to get the same message across, 'beating upon' those shepherds, who immediately went 'with haste' to worship the mystery of love in a stable. That partnership of music and wor- ship has continued ever since and perhaps most conspicuously in the caroling which marks the night of the Nativity.

Bishop Michael Marshall is Archbishops' Adviser on Evangelism.

Previous page

Previous page