A noble experiment in tolerance deliberately wrecked

Frederic Raphael

THE SEPHARDI STORY by Chaim Raphael

Valentine Mitchell, £18.50, £9.95, pp.294

Lewis Namier, quizzed on why he did not concern himself with the history of his own people, notoriously retorted, 'The Jews don't have a history, they have only a martyrology'. He preferred to analyse the personal circumstances of 18th-century members of parliament rather than to reopen the cases of murder, theft and persecution which, he feared, typified Jewish history. Vanished supremacies entertained him more than persistent

inferiorities.

My namesake, who is not a relation of mine, is an Ashkenazi — whose family connections are with central and eastern Europe — while his subject is the branch of Jewry which stayed close to the Mediterranean basin, the Sephardi, whose happiest era preceded the expulsion from Spain 500 years ago. A recent issue of the Spanish news magazine, Cambio 16, celebrated the Madrid conference — which seems to have gone considerably to Spanish cabezas — with a cover announc- ing that Christians, Moors and Jews were `otra vez in Esparta'. The destruction of the triune society whose great cities were Cordoba and Granada was an act of Christian policy which presaged the reduction of Spain from a position of European hegemony to one of bankruptcy. Whether or not the ruin of the Jews entailed the decline of Spain, despite the immense wealth pillaged from the Americas, is disputable; what is certain is that Andalucia, in particular, never recovered and that, with all its strains, a noble experiment in tolerance was deliberately wrecked.

The Jews never, of course, enjoyed equality in Islamic societies (although Elie Kedouric argues that they were quite happily placed in the Ottoman Empire, which western policy destroyed in order to replace it with the Arab states on whose good faith and immutable borders the Foreign Office still sets so much stock). The Jews of the Diaspora might be favourites of the Sultan or the Caliph, but they were always his subjects. From time to time, even during the golden age, there were periods of persecution and instances of more or less mass-murderous caprice. Islam had a place for 'people of the book' — Christians as well as Jews but it was an inferior one, which denied them the right to carry arms and made them pay for the `privilege'.

In Andalucia, Christian zealots were the first to fracture the delicate balance by committing acts of flagrant provocation, after which they insisted, by their intransi- gence, on the martyrdom which the Moors knew would create if not a casus belli, certainly grounds for eventual divorce. The Jews lacked such divisive militancy; they were the willing, and often very able, lieutenants both of the Moors and of the Christians, after the reconquista. Their loyalty was to their own faith; the rest was politics. They imagined that they could live with Christianity as they had with Islam, but Ferdinand and Isabella lacked the Sultans' capricious geniality. Spanish Jews had to convert or leave; the Inquisition became vigilant in the detection, and execution, of those Matranos who only pretended' to change their religion. Portugal supplied a temporary refuge, but followed the Spanish example seven years later. What comedy there is in this early draft of the final solution lies in the fact that the Jews, like the Moors, had already become so integral a part of Spain that affectations of racial purity became an obsession in a society which was, and would always be (look at them!), enrichingly mongrelised.

The Jews may have been expelled, but their expertise, in a number of fields, was irreplaceable, with the result that 'Britain's oldest allies', as the cant described them, were not so much the Portuguese as the Jews who, so to say, sailed under Portuguese flags of convenience (which did not prevent the Inquisition from doing its Pious work in Portugal too). As Raphael emphasises, the strength of the Jews, despite their manifest vulnerability, lay in their cohesive diversity: ever since the exile in Babylon, they had learnt to live with dispersal and to improvise in the face of catastrophe. They had many communities, each with its local characteristics (the Yemeni Jews were — and even in Israel are — quite distinct from the Moroccans, Who are also Sephardic), but communica- tion between the Jews of Baghdad and of Cordoba was both copious and speedy. It began with questions of ritual, addressed to the sages of the orient, but secular business Used the same channels. Raphael draws eagerly on the evidence of the Cairo geniza, which is a miraculously preserved archive of Jewish correspon- dence from the time of Maimonides and before.

The Jewish role as middleman derived not from some racial tendency (in fact, Jews were 'naturally' farmers and soldiers before they were usurers or agents) but from the facility with which they dealt across frontiers and in various tongues. The Sephardi can most easily be distinguished from Askenazi, who often speak Yiddish, by their use of Ladino, a dialect based on Spanish. Raphael tells a splendid and Poignant story of his youth when he attend- ed a reconciliatory meeting in Malaga, at

which a Sephardic rabbi made a speech in 15th-century Castilian of a linguistic resource not heard in Spain since the exile. The willingness even of Franco to re-admit Spanish Jews gives rise to the modern myth of the beautiful Jewess who arrives in Toledo and, after bewitching the town in Zuleika style, walks one day to a great house in the centre of the city, takes a key from her pocket and opens the antique lock on the patio door and tells the modern tenants that she has returned to her family's house.

No such acts of reclaim are likely, in fact. The Madrid conference was loud with talk of Arab lands, but no mention is ever made of the systematic dispossession of Jews, especially in Iraq, where they were cynically and savagely picked clean before being 'allowed' to repair to Israel. Arab (and Iranian) affectations of grievance and ill-treatment

have succeeded in camouflaging depredations and brutalities which do not justify, but certainly match, Israeli appropriations. Sentimentalists, of which am one, may look back on Cordoba as an emblem of hope — the little synagogue where Maimonides worshipped is a simple room which contrasts sweetly with the ostentation of the mezquita — but there is, I fear, little prospect of that balance of forces, spiritual and cultural, which gave tolerance, and even assimila- tion, a good name, although the `excommunication' of Spinoza remains a prime instance of the Jewish religious intolerance which may yet destroy Israeli cohesion. One has only to read The Metsudah Kuzari, a Sephardic devotional work some 800 years old, which is peremptory with non-negotiable assertions (and charges of heresy for those who question them) to realise that, given the clout, Jewish inquisitions might be no less incendiary than Christian.

Raphael is both modest and thorough. His book bulges with information and he is as dispassionate as his enthusiasm allows. Only when he starts to analyse the present rapports de forces in Israel, where the once despised Sephardi are now demographically dominant, does a certain Namieresque finickiness creep in and I am tempted to creep out (must I stay to read that the Israeli Labour Party 'have now become status quo in aim'?). The parade of `notables' of Sephardic origin, from Sir Joshua Hassan to Jacques Attali (!?), via David Levy and Shlomo Hillel (press officer, Jerusalem), is vulgar and parochial after the brilliant, tragic cast whose long and varied history of exile and massacre somehow manages to exhilarate rather than depress those of us who, thanks to whatever agency of fate or providence, can have the painful pleasure of reading it.

Previous page

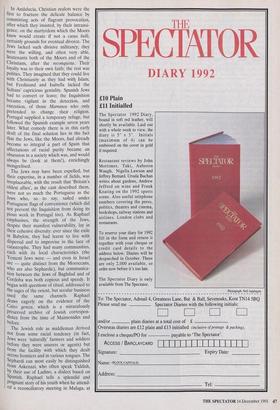

Previous page