CRISIS THE DOLLAR

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT THE ending of discrimination against the imports of dollar goods followed hard on the an- nouncement by Washington that new loans from their Develop- ment Loan Fund were to be spent only on American goods. This is not the first time that liberalism in Great Britain has been matched by protectionism in the United States, But I do not think that Washington would have chosen this particular moment to advertise its 'Buy Ameri- can' affront to multi-lateral trade if it had not found itself in a tight exchange corner. The fact that we British have gone out of our way to repay the $250 million loan from the Export-Import Bank, which was not finally due until 1965, is suffi- cient proof that the American Treasury is seriously worried by its continuing loss of gold. If the foreign holders of dollar balances, who are not as friendly and helpful as we are, were suddenly to get the idea that the dollar was overvalued, the flight from that currency would be so quick that the next announcement from Washington would be a refusal to sell gold. But we have not yet come to that point. The calculating foreigners are wait- ing to ke what sort of settlement—inflationary or no—is reached in the steel strike now that the men have been ordered back to work. In the meantime Mr. Robert Anderson, the Secretary of the Treasury, is making determined efforts to stem the gold drain by improving the balance of pay- ments.

Ordinarily the United States have a favourable balance of payments on current trading account which is turned into a deficit by defence spending abroad, foreign aid and overseas investment. For example, in 1958 their merchandise exports exceeded their imports by $3,300 million, yet the final deficit was $3,500 million. But in the first half of this year their merchandise imports actually exceeded their exports by $700 million. To what extent this adverse result was brought about by the disruption of the steel strike and to what extent by the fact that American goods.are pricing them- selves out of the world markets through the rise in their domestic costs it is too early to determine, but it is an ominous development. It means that the whole of the foreign aid, the whole of the direct military spending abroad and the whole of the private investment overseas have to be met either by the sale of gold or by increasing the short-term dollar debt to foreigners. The total deficit in the first half of this year came to $1,900 million (excluding the $1,375 million subscribed to the International Monetary Fund), of which $1,400 million went to increase the short-term dollar debt. This is an uncomfortable and indeed dangerous position for the dollar.

The first line of defence, as Mr. Anderson sees it, is to cut foreign aid. The second line, as Presi- dent Eisenhower sees it, is an initial settlement with Russia which will enable direct military

loans in 1958 were $2,600 million and this half-yenf 'Im $1,200 million. and in the first half of 1959 to4 'eti deficit of $500 million (thanks to a small declinck domestic interest rates). Under government con' °1] countries, partly by direct cuts in the forces thei spending abroad to be pruned. Last year 'inv)ils',:flac, ibles' and military payments came to a deficit Of in military spending). Government grants and 'lle $1,200 million. The private capital outflow in the rel same periods was $2,800 million and $800 milli( n respectively (restrained this year by the rise in 'Of trol, then, there was a capital outflow last yea -tk of $3,800 million and it is Mr. Anderson's hope cut it by half (he has reduced it this year by abon IN in the cost of keeping American forces in theif III 10 per cent.), partly by getting the allies to share 'in

ha selves, partly by persuading Britain and Germat I, ,

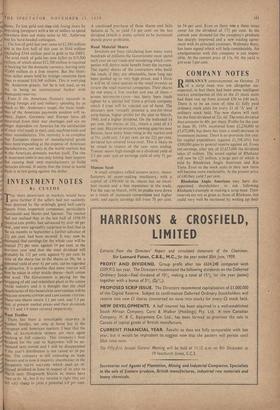

; trii to take more of the burden of providing loans fpi the underdeveloped nations, partly by requirin the recipients of American aid to spend it c American goods. It must be galling to an Ameri' can Secretary of State, reared in the protectionist school, to see about half the economic aid prO' vided by his Treasury spent outside the Unitd COMPANY MEETING

Ito

of ; IT

I.

,,States. To lose gold and then risk losing more by Providing foreigners with a lot of dollars to spend elsewhere does not make sense to Mr. Anderson and his hard-headed colleagues.

The loss of gold last year came to $2,300 million and in the first half of this year to $844 million (Including $344 million paid in gold to the IMF). The total stock of gold has now fallen to $19,500 million, of which about $12,500 million is required Lis backing for the domestic currency, leaving only $7,000 million as a free reserve. But the short- term dollar assets held by foreign countries have risen to around $18.500 million. This is worrying Mr. Anderson greatly, for he is not used, as we are, to being an international banker with Inadequate reserves.

Even if the American Treasury succeeds in elating foreign aid and military spending by as Much as Mr. Anderson's target, the basic weak- ness of the American payments position will re- Main. Japan, Germany and Europe have all recovered from their war shortages and are no longer dependent on America for the satisfaction Of their vital needs in steel, coal, machine tools and Other manufactures. The recovery is so complete that European exports of manufactured goods have been expanding at the expense of American Manufactures, not only in the world markets but In the American domestic market itself. The rise In American costs is not only hitting their exports but causing their own manufacturers to build factories abroad. It seems that the trend in world trade is at last going against the dollar.

Previous page

Previous page