Theatre

Crazy For You (Prince Edward)

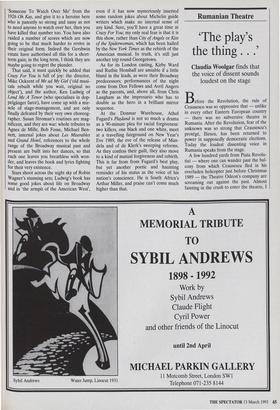

Playland

(Donmar Warehouse)

Only one hand clapping

Sheridan Morley

Major Recessions and Great Depres- sions have always been very good news indeed for the Gershwins; the period of their first great fraternal fame on Broad- way and in Hollywood more or less coincid- ed with the immediate aftermath of the Wall Street Crash, and here we are 60 years later with a retread of their Girl Crazy, made over as Crazy For You (at the Prince Edward), and rather curiously advertised as a 'new' Gershwin musical; in which case, stand by for new musicals by Ivor Novello and Noel Coward.

What has happened to the original Girl Crazy is that the book has been totally abandoned and a new one created by Ken Ludwig, while the score has been artificially boosted by the inclusion of several Gersh- win classics from other shows. The result has been a huge Broadway hit these last two seasons, and looks all set to repeat its triumph in London. Why then do you hear in this column the sound of only one hand clapping?

First, perhaps, because I can't altogether accept the claim of the present production team that the original Girl Crazy is 'unre- vivable': what they mean is that it wouldn't be a huge Broadway hit in present circum- stances, though as a small-stage classic it worked well enough when I saw it at the Shaw Festival in Canada about five years ago. But fashions in musicals change, and another 50 years from now it's my guess that they may well be reviving Girl Crazy instead of Crazy For You.

Secondly, the original score, though weaker than what we have now, had its own energy and integrity: if you rope in `They Can't Take That Away From Me' and tack it on to the front of the original 'But Not For Me', you have immeasurably weakened both songs; if you then also rope in Gertrude Lawrence's heartbreaking `Someone To Watch Over Me' from the 1926 Oh Kay, and give it to a heroine here who is patently so strong and sassy as not to need anyone to watch over her, then you have killed that number too. You have also raided a number of scores which are now going to be that much harder to revive in their original form. Indeed the Gershwin estate have authorised all this for a short- term gain; in the long term, I think they are maybe going to regret the plunder.

That said, it must quickly be added that Crazy For You is full of joy: the director, Mike Ockrent of Me ad My Girl Cold musi- cals rebuilt while you wait, original no object'), and the author, Ken Ludwig of Lend Me A Tenor (who specialises in dop- pelganger farce), have come up with a mir- acle of stage-management, and are only finally defeated by their very own choreog- rapher. Susan Stroman's routines are mag- nificent, and they are war: whole tributes to Agnes de Mille, Bob Fosse, Michael Ben- nett, internal jokes about Les Miserables and Grand Hotel, references to the whole range of the Broadway musical past and present are built into her dances, so that each one leaves you breathless with won- der, and leaves the book and lyrics fighting for their very existence.

Stars shoot across the night sky of Robin Wagner's stunning sets; Ludwig's book has some good jokes about life on Broadway and in 'the armpit of the American West',

even if it has now mysteriously inserted some random jokes about Michelin guide writers which make no internal sense of any kind. Sure, you'll have a great time at Crazy For You; my only real fear is that it is this show, rather than City of Angels or Kiss of the Spiderwoman, which has been hailed by the New York Times as the rebirth of the American musical. In truth, it's still just another trip round Georgetown.

As for its London casting, Kirby Ward and Ruthie Henshall are amiable if a little bland in the leads, as were their Broadway predecessors; performances of the night come from Don Fellows and Avril Angers as the parents, and, above all, from Chris Langham as the impresario who has to double as the hero in a brilliant mirror sequence.

At the Donmar Warehouse, Athol Fugard's Playland is not so much a drama as a 90-minute plea for racial forgiveness: two killers, one black and one white, meet at a travelling fairground on New Year's Eve 1989, the eve of the release of Man- dela and of de Klerk's sweeping reforms. As they confess their guilt, they also move to a kind of mutual forgiveness and rebirth. This is far from from Fugard's best play, but yet another poetic and haunting reminder of his status as the voice of his nation's conscience. He is South Africa's Arthur Miller, and praise can't come much higher than that.

Previous page

Previous page