Drink 2

The perils of drinking out

Alan Watkins

What follows is not about drinking in but about drinking out. Drinking in, at home, is fairly straightforward, given that wine is a complicated substance in the first place. Drinking out, in restaurants, bars or wherever, is subject to greater perils and dangers. When I began drinking in El Vino (always incorrectly called El Vino's) in Fleet Street 37 years ago, I would be horri- fied if a round of drinks came to £2. Today the equivalent would be £150 — taking into account what I earn now and earned then, which was £20 a week. And it is virtually impossible to spend that amount on a round of drinks. Evenif it were, I would no more think of spending £150 than I would contemplate buying a racehorse or a yacht.

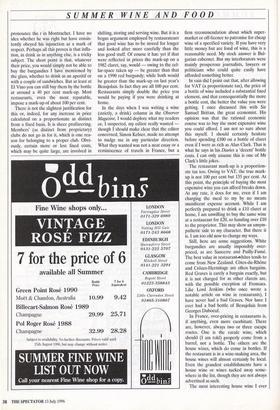

• Nevertheless — this is the strange thing — drink did seem remarkably cheap in those days. The standard tipple, Chablis, was 12.5p a glass. Montrachet, Meursault and Vosne-Romanee were 17.5p. Philip Hope-Wallace told me it was correct to 'So who'd get custody of our supermarket loyalty cards?' pronounce the t in Montrachet. I have no idea whether he was right but have consis- tently obeyed his injunction as a mark of respect. Perhaps all this proves is that infla- tion, in drink as in anything else, is a tricky subject. The short point is that, whatever their price, you would simply not be able to buy the burgundies I have mentioned by the glass, whether to drink as an aperitif or with a couple of sandwiches. But at least at El Vino you can still buy them by the bottle at around a 40 per cent mark-up. Most restaurants, even the most reputable, impose a mark-up of about 100 per cent.

There is not the slightest justification for this or, indeed, for any increase in price calculated on a proportionate as distinct from a foxed basis. It is sheer profiteering. Members' (as distinct from proprietary) clubs do not go in for it, which is one rea- son for belonging to a proper club. Obvi- ously, certain more or less fixed costs, which may be quite large, are involved in shifting, storing and serving wine. But it is a bogus argument employed by restaurateurs that good wine has to be stored for longer and looked after more carefully than the less good stuff. Of course it has: yet if that were reflected in prices the mark-up on a 1982 claret, say, would — owing to the cel- lar-space taken up — be greater than that on a 1990 red burgundy; while both would be greater than the mark-up on last year's Beaujolais. In fact they are all 100 per cent. Restaurants simply double the price you would be paying if you were drinking at home.

In the days when I was writing a wine (strictly, a drink) column in the Observer Magazine, I would deplore what my readers or, I suspected, my editor really wanted though I should make clear that the editor concerned, Simon Kelner, made no attempt to nudge me in any particular direction. What they wanted was not a neat essay or a reminiscence of travels in France, but a firm recommendation about which super- market or off-licence to patronise for cheap wine of a specified variety. If you have very little money but are fond of wine, this is a reasonable need. My stock answer is Bul- garian cabernet. But my interlocutors were mainly prosperous journalists, lawyers or politicians who could quite easily have afforded something better.

In vain did I point out that, after allowing for VAT (a proportionate tax), the price of a bottle of wine included a substantial fixed element, and that consequentially the more a bottle cost, the better the value you were getting. I once discussed this with Sir Samuel Brittan, the great economist. His opinion was that the rational economic course was to buy the most expensive wine you could afford. I am not so sure about this myself. I should certainly hesitate before spending £100 on a bottle of claret even if I were as rich as Alan Clark. That is what he says in his Diaries a 'decent' bottle costs. I can only assume this is one of Mr Clark's little jokes.

The restaurant mark-up is a proportion- ate tax too. Owing to VAT, the true mark- up is not 100 per cent but 135 per cent. At this point, the principle of buying the most expensive wine you can afford breaks down. At any rate, it does for me, even if I am charging the meal to my by no means munificent expense account. While I am perfectly prepared to drink a £10 claret at home, I am unwilling to buy the same wine at a restaurant for £20, so handing over £10 to the proprietor. This may show an unsym- pathetic side to my character. But there it is. I am too old now to change my ways. Still, here are some suggestions. White burgundies are usually impossibly over- priced, as are Sancerre and Puilly-Fum6. The best value in restaurantwhites tends to come from New Zealand. Cotes-du-Rhone and Crozes-Hermitage are often bargains. Red Graves is rarely a bargain exactly, but it is not charged for as other clarets are, with the possible exception of Fronsacs. Like Lord Jenkins (who once wrote a notable article on wine in restaurants), I have never had a bad Graves. Nor have I ever had a bad bottle of Beaujolais from Georges Duboeuf.

In France, over-pricing in restaurants is, if anything, even more exorbitant. There are, however, always two or three escape routes. One is the carafe wine, which should (I am told) properly come from a barrel, not a bottle. The others are the house wines, which do come in bottles. If the restaurant is in a wine-making area, the house wines will almost certainly be local. Even the grandest establishments have a house wine or wines tucked away some- where in the list, though they are not always advertised as such.

The most interesting house wine I ever drank was a pale, but full red called Mani- cle, at Alain Chapel in Mionnay outside Lyon. It came from Bugey to the east. I tracked down the maker through the kind- ness of the late Alain Chapel and tried to interest the Wine Society. The society was enthusiastic but the maker was not. He was evidently perfectly content to supply Chapel, keeping clear of foreign entangle- ments. But why, I wonder, do restaurants here not choose two or three good house wines? They could still, like French restau- rants, continue to display their extensive and expensive lists.

Previous page

Previous page