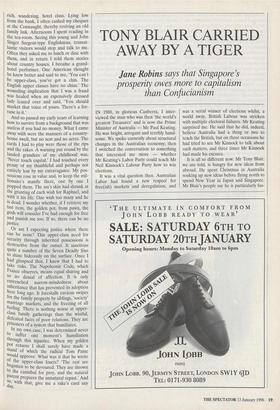

TONY BLAIR CARRIED AWAY BY A TIGER

Jane Robins says that Singapore's prosperity owes more to capitalism than Confucianism IN 1988, in glorious Canberra, I inter- viewed the man who was then 'the world's greatest Treasurer' and is now the Prime Minister of Australia — Mr Paul Keating. He was bright, arrogant and terribly hand- some. We spoke earnestly about structural changes in the Australian economy; then I switched the conversation to something that interested me more — whether Mr Keating's Labor Party could teach Mr Neil Kinnock's Labour Party how to win elections.

It was a vital question then. Australian Labor had found a new respect for free(ish) markets and deregulation, and was a serial winner of elections whilst, a world away, British Labour was stricken with multiple electoral failures. Mr Keating surprised me. He said that he did, indeed, believe Australia had a thing or two to teach the British, but on three occasions he had tried to see Mr Kinnock to talk about such matters, and three times Mr Kinnock had made his excuses.

It is all so different now. Mr Tony Blair, we are told, is hungry for new ideas from abroad. He spent Christmas in Australia soaking up new ideas before flying north to spend New Year in Japan and Singapore. Mr Blair's people say he is particularly fas- cinated by Singapore as an East Asian economy that is entirely at odds with the Tory vision of the Asian Tigers. Labour, like the Tories, is indulging in a spot of `Tigerism' — citing the policies of success- ful East Asian states as models for a New Britain.

State-centred Singapore is an interesting choice, contrasting nicely with the Tories' new-found passion for laissez-faire Hong Kong. Most significant is the Singaporean approach to social welfare, which involves forcing the population to contribute more than 30 per cent of its income to a state- managed savings scheme that covers contributors' pensions, unemployment insurance and other needs. What each individual gets out of the central fund is directly related to what he or she puts into it. There is no element of redistribution. What's more, the scheme looks remarkably similar to the one proposed by Mr Frank Field, the man on the Labour backbenches who is, with the full support of Mr Blair, working out ideas for reforming the British welfare state.

Singapore is understandably fascinating to a left-of-centre party trying to find a `middle way'. It espouses low tax, and yet requires that a third of one's income is saved. Thus it can boast of a small state sector, whilst maintaining a huge 'quasi- state', and it is proudly interventionist. Its people are richer than us, with a per capita GDP this year above US$30,000, against our own US$20,500.

The trip has provided Mr Blair with the vocabulary to challenge the Conservatives' Hong Kong-based Tigerism. In Asia, Sin- gapore and Hong Kong are rivals of old. The Singaporeans deplore the Hong Kong people's lack of planning and direction and their love of the dirty, entrepreneurial free-for-all. Hong Kong in turn despises the Singaporean passion for control and order and Singapore's pathological cleanli- ness. Now we may have the splendid vision of the rivalry being exported to Britain. Every time Mr Major cites the virtues of Hong Kong's low-tax, deregulated free- market economy, Mr Blair will be able to retort that there is an alternative, a third way, a way with the impeccable credentials of `Tigerism' — all based on the Singa- porean model.

`Tigerism' has been gathering momen- tum since Mr Major brought it up at the Conservative conference last October, proclaiming that if we are to compete with the Pacific Basin, then Britain should be the 'enterprise centre of Europe' and 'high spending and high taxes are no longer an option'. (In the context of Asia, public spending of even 40 per cent of GDP amounts to high taxes — being roughly twice the rate of most Asian Tigers.) The sentiment was echoed by Mr Kenneth Clarke, Mr Stephen Dowell and Mr Brian Mawhinney. Then the Hong Kong gover- nor, Mr Chris Patten, caused a stir by mak- ing his own speech saying the Conservatives should learn from the low- tax ways of the British colony. The message was that Tory wets along with the Right should subscribe to Tigerism.

But there is a danger in this. Until now Tigerism has involved a fairly vague obser- vation of Asian competitiveness, accompa- nied by the exhortation that we in the West cannot be complacent; we need to keep our economies vibrant to compete in the forth- coming 'Pacific Century'. That is all very well, but now the debate is shifting up a gear with the intimation that Asian eco- nomic policies provide the best model to ensure economic growth, that Asia knows better than America or Europe how best to run a continent. After all, Hong Kong, Sin- gapore, South Korea and Taiwan have growth rates three times the size of our own. The strength of the argument appears to be self-evident.

There is a danger of being carried away, and it is worth remembering the shortcom- ings of Tigerism. First, but least important, there are profound differences between those young Asian economies and our own. Singapore has no unemployment, Hong Kong has a vast Chinese hinterland of cheap labour. Second, the Asian economies are starting to run into West- ern problems. Hong Kong is experiencing a hint of unemployment for the first time in years. South Korea is contemplating the need for welfare provision. The non-Singa- porean Tigers are becoming alert to the need for greater regulation — to stop department stores collapsing in Seoul and pollution on the traffic-choked streets of Bangkok.

But 'Asian growth' cannot at heart be put down to any special Asian values. It is based on good, old-fashioned capitalism. If Confucianism is so vital, how come it failed to produce growth for centuries, and only did so when Western-style capitalism began to make its mark? But most significant is the view voiced by Mr Paul Krugman, a prolific economics professor at Stanford University. He observes that very high economic growth can take place under all sorts of political and economic regimes and reminds us that when, in 1961, Khrushchev pounded his shoe on the United Nations podium and announced 'we will bury you', it was an economic rather than a military boast. The Soviet Union at the time was transforming itself from a peasant society into an indus- trial juggernaut, its growth rate was thought to be three times that of the Unit- ed States, electricity output had increased sevenfold since the war, Kennedy was anx- ious. Newspapers warned that the USSR was storming its way to world economic domination. Economists wondered whether the Soviet collectivist and authori- tarian state was inherently better at achieving economic growth than free-mar- ket democracies. Mr Krugman believes that much of the current hyperbole about East Asia is simi- lar, that growth in the Tiger economies, like the growth in the Soviet economy in the 1950s and early 1960s, owes more to the sheer increase in inputs — the mobili- sation of labour and resources, for example — than it does to increases in efficiency. The distinction is important because, eco- nomically speaking, it is not surprising that higher inputs lead to higher growth. It is not an economic miracle, just an economic expectation. Plus, the super-growth is a one-off, it must begin to slow down.

Of course, that is not to suggest that the Tigers will go the way of the former Soviet economy. But it does suggest a note of cau- tion to any politician arguing that Tigerism holds the answer to our economic difficul- ties. It was simplistic to look at Soviet growth and conclude that the West was in need of a heavy dose of central planning, and it would be similarly short-sighted to accept Tigerish policy prescriptions just because the Tigers are, at the moment, kings of the jungle.

Jane Robins is editor of The Week in West- minster.

Everyone looks good in a tux.'

Previous page

Previous page