BOOKS

From boy scout to myth

Colin Welch

HERGE AND TINTIN, REPORTERS by Philippe Goddin translated by Michael Farr

Sundancer, f.25

Ifirst met Tintin near Tildonk in Bel- gium in the autumn, it must have been, of 1944. We were out of the line, billeted in the mansion of a sugar tycoon who, thought to have been too sweet to the departing Germans, had departed too. It looked much like Captain Haddock's ancestral seat, Marlinspike Hall, an impos- ing edifice unmistakably Belgian rather than English and perhaps more like an Hotel de Ville or Mairie than a gentleman's château.

A slight snag here? You can easily enough translate the text into English or, as has been done, into almost every lan- guage under the sun. The utterances of Snowy (in French, Milou) are readily transposed from the original — `wooah', `wouah' or `waa000uuu', the piteous howl with which the poor little dog laments his master's death. You can find acceptable substitutes for Captain Haddock's spec- tacular floods of bibulous ire and invective — though at least one uncomplimentary epithet, 'clysopompe' was put into his mouth by his creator Herge without realis- ing what it meant. What does it mean then? I'm glad you asked that question. Well, er, so far as my medical French stretches, it appears to be a dire arrange- ment of tubes more properly inserted into the rectum for intestinal irrigation than into a strip cartoon for children. But the pictures can't, of course, be transplanted. For instance, walking through what is apparently a little English seaport, his face buried in a newspaper, Captain Haddock crashes smack (in French, I fancy, DZING! or DziorrmIG!) into one of those iron publicity pillars, so characteristic of bloody abroad yet un- known here. The Captain's astonishment and rage are in the circumstances very understandable. But what child would ever worry about such trifling incongruities? And anyway most of Tintin's adventures take place in exotic places like Tibet or on the moon, meticulously researched, with which few children or grown-ups are famil- iar.

The friendly farmer and his wife next door invited me to dinner. They regaled me with the horrors of life under German occupation. Above all, the Germans had even paid such high wages to munitions workers that it was impossible to keep anyone on the land. `Tiens!' , I cried, or words to that effect. I might have been listening to a farmer moaning at home. Monsieur went out to the cows. 'Can you read to the children while I do the din- ner?', Madame asked, and handed me a Tintin book. The children wriggled with eager delight. They knew well what to expect, were my French up to it. I was captivated at once: the drawings so bright, so clear, so deceptively simple, so easy to `read'. And the characters: never in a children's book had I bumped into grown- ups depicted with such wild humour, at once broad and sophisticated.

The Captain himself, met then or later with children of my own, more or less permanently drunk and explosively irasci- ble, yet fundamentally generous and brave. The Professor, endlessly inventive and resourceful, stone deaf, misunder- standing all the questions, coming up with all the answers, hilariously inconsequen- tial. Tintin dives for treasure. `It worries me a bit', says the Captain, `that Tintin hasn't come up again'. No', replies the Professor, 'but I was a great sportsman in my youth'. Ah me . . .

Then there are the two detectives, the moustached Thompsons, identical twins, equally and impenetrably stupid, charged to protect Tintin, themselves in constant need of protection and rescue. The Profes- sor has invented a space-saving wall-bed. Descending to open, it inevitably crowns the Thompsons, producing multi-coloured stars and jamming their bowler hats hard down over their ears. Closing again, it carries the dazed Thompsons with it into the wall. The Professor is surprised and mildly grieved: 'Between ourselves, I wouldn't have expected such childish pranks from them. They looked quite sensible. . .'. Looks can deceive.

Then there is Snowy himself, alert, curious, noisy, enthusiastic, all dog, pre- sent in almost every frame, inspecting, head on one side, all that goes on, in- tervening decisively when necessary, almost permanently attended by a large question or exclamation mark. I treasure specially a drawing, reproduced in this book, of the enormous skeleton of the prehistoric Diplodocus Gigantibus in the museum at Klow. The curator is staring in horror; a vast bone is missing from its right foreleg. We share his perplexity till we note Snowy fleeing, bone clamped firmly between his teeth.

As we read and looked at the pictures in the flickering firelight, poor old Herge (actually Georges Remi, who reversed his initials to make his pseudonym, R.G., thus Herge) was having rather a rough time not far away. He had insouciantly gone on appearing in a newspaper the Germans had `stolen' and which was otherwise full of inflammatory Nazi propaganda. Came the Liberation, the paper was closed and all journalists and other contributors who had worked on it during the Occupation were banned. Herge was arrested four times, though only for a few hours, and spent one night in a cell. His stuff became too hot to handle. Printers refused it; the journalists' union blacked him, as the Gestapo had partly blacked him before. He appears to have been outraged, and retained bitter memories of `an experience of complete intolerance'.

To what extent, if any, had he asked for it? This book, a confusing account by various hands of the life, times and works of Herge, is not a great help. It mentions pictures which, at the height of the war, `featured one or other stereotype of a Jew'. It reproduces none. It pleads that their full `tactlessness' could only. be gauged when all the horrors of the Holocaust were known, as they were not known then, either to Herge or to his detractors. Moreover, Herge caricatured many, many stereotypes. Had Hitler massacred the blacks, would his irreverent drawings of the Congolese have appeared tactless? Perhaps so, in our hypersensitive age.

The text of the book is frequently vague, evasive, abstract, at times unintelligible, though whether this is the translator's fault or the original writer's is difficult to say. What are we to make of sentences like this: `Nevertheless at the moment where one gets ready to accuse Snowy of having rummaged in the dustbins of the Gestapo, too many pictures seemed crushing for their author'?

Herge appears to have known Leon Degrelle, presumably the leader of the Belgian Fascists, though the book doesn't say so very explicitly. An agent of Degrel- le's certainly offered Herge during the war a job as official illustrator to the Belgian Fascist movement. He refused it. Why he was offered it, why he refused, we are not told.

What sort of chap was Herge really? We meet him first as a Catholic boy scout, and that he seems to have remained in essence all his life. Scouting, he records, gave him `a taste of friendship, love of nature, animals, games. It is a good school. All the better if Tintin bears the hallmark.' Scout- ing took him to the Pyrenees, his 'Tibet', 300 kilometres on foot. It took him walking and camping all his life. It was scouting which presumably later clapped rucksacks onto wives No 1 and 2, one wife replacing the other after an extremely muddling mental, moral and marital crisis, which wife No 2 in an unusually sensible and sympathetic memoir, effectively discounts.

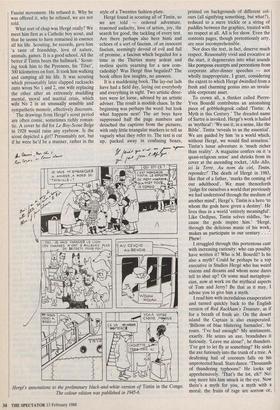

The drawings from Here's scout period are often comic, sometimes richly roman- tic. A cover he did for Le Boy-Scout Beige in 1928 would raise any eyebrow. Is the scout depicted a girl? Presumably not, but if he were he'd be a stunner, rather in the style of a Twenties fashion-plate.

Herge found in scouting all of Tintin, so we are told — ordered adventure, reasoned audacity, love of action, joy, the search for good, the tackling of every test. Are there perhaps also here hints and echoes of a sort of fascism, of an innocent fascism, seemingly devoid of evil and full of promise, a fascism which beguiled for a time in the Thirties many ardent and restless spirits yearning for a new com- radeship? Was Herge thus beguiled? The book offers few insights, no answers.

It is a maddening book. The lay-out lads have had a field day, laying out everybody and everything in sight. Two artistic direc- tors were let loose, advised by an artistic adviser. The result is modish chaos. In the beginning was perhaps the word: but look what happens next! The art boys have suppressed half the page numbers and detached the captions from the pictures, with only little triangular markers to tell us vaguely what they refer to. The text is cut up, packed away in confusing boxes, Herge's annotations to the preliminary black-and-white version of Tintin in the Congo. The colour edition was published in 1945-6. printed on backgrounds of different col- ours (all signifying something, but what?), reduced to a mere trickle or a string of puddles between the graphics, treated with no respect at all. All is for show. Even the contents pages, though pretentiously arty, are near incomprehensible.

Nor does the text, in fact, deserve much respect. Reasonably vivid and evocative at the start, it degenerates into what sounds like pompous excerpts and perorations from corporate after-dinner speeches — not wholly inappropriate, I grant, considering the extent to which Herge dwindled from a fresh and charming genius into an invalu- able corporate asset.

To crown all, a thinker called Pierre- Yves Bourdil contributes an astonishing piece of gobbledegook called A Myth in this Century.' The dreaded name of Sartre is invoked. Herge's work is hailed as 'mythical': 'We use it, in a sense, like the Bible'. Tintin 'reveals to us the essential'. We are guided by him 'in a world which, without Herge, we would find senseless.' Tintin's lunar adventure is 'much richer than reality'. A magazine confers on it 'a quasi-religious sense' and shrieks from its cover at the ascending rocket, 'Allo Allo, ici la Terre. Au nom du ciel, Tintin, repondez!' The death of Herge in 1983, like that of a father, 'marks the coming of our adulthood'. We must thenceforth `judge for ourselves a world that previously we had understood through the medium of another mind', Herge's. Tintin is a hero 'to whom the gods have given a destiny'. He lives thus in a world 'entirely meaningful'. Like Oedipus, Tintin solves riddles, 'be- cause the gods inspire him."Herge, through the delicious music of his work, makes us participate in our century . . Phew!

I struggled through this portentous cant with increasing curiosity: who can possibly have written it? Who is M. Bourdil? Is he also a myth? Could he perhaps be a top executive in Studios Herge who has weird visions and dreams and whom none dares tell to shut up? Or some mad metaphysi- cian, now at work on the mythical aspects of Tom and Jerry? Be that as it may, I advise you to give him a myth.

I read him with incredulous exasperation and turned quickly back to the English version of Red Rackham's Treasure, as if for a breath of fresh air. On the desert island the Captain is also exasperated. `Billions of blue blistering barnacles', he roars. 'I've had enough!' My sentiments, exactly. He seizes an axe, brandishes it furiously. 'Leave me alone!', he thunders. `I've got to let fly at something!' He sinks the axe furiously into the trunk of a tree. A deafening hail of coconuts falls on his unprotected head. Stars dance. 'Thousands of thundering typhoons!' He looks up apprehensively. 'That's the lot, eh?' No: one more hits him smack in the eye. Now there's a myth for you, a myth with a moral: the fruits of rage are sorrow or, watch it, nuts can hurt.

To avert the wrath of M. Bourdil, let me be quite fair. As you'd expect, the sub- ordination of the word to the image in this book does mean page after page of marvel- lous pictures, not only brilliant in them- selves but profoundly interesting as show- ing how Herge worked. We see his draw- ings in all their stages, rough draft, polished up, traced, inked in, coloured, completed. We see how careful and solid and craftsmanlike his work is, everything as carefully constructed as a fine old chest of drawers, nothing skimped or left to chance. We also realise, or I did, that Herge was an even finer draughtsman than the finished product might always suggest. Those first sketches, as also all pictures done for his own pleasure, are, like Const- able's, unbelievably free, bold, fleet, wild and flowing, full of expression and move- ment. It would be absurd, I think, to maintain that in the long process of render- ing them absolutely clear, precise and `legible' nothing was lost at all. If this book is worth £25, it must be for the pictures alone.

Previous page

Previous page