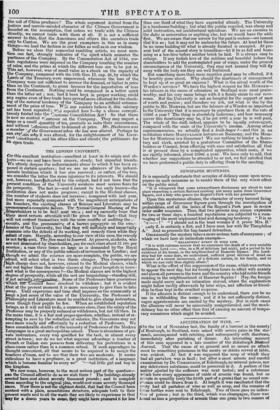

EAST INDIA COMPANY—THE CHINA. TRADE.

NOTWITHSTANDING the determination of his Majesty's Ministers to treat the question of India, the commerce to which, with a few useless and inoperative restrict-ions, has been for a number of years free—and that of China, the trade to which is strictly a monopoly in the hands of the East India Company—as one .and the same, we cannot help looking on them as separate and distinct in all points of view. The mere fact that India is a colony, and China an independent kingdom, is in our opinion sufficient to prove the propriety of considering these questions not as connected together, which they are only in reference to the Company, but as separate, which they are in all their other re- lations. Tbequestion _a India is one of great complexity. The /.; power of the -Company there- i has grown up n the lapse of one bun- ,' dred and seventy years, from a gram of mustard-seed to a tree that I covers the earth with its branches. Its ramifications are so numerous I and so extended, that much and long and minute attention is required ‘ to trace only a few of them. India calls for the attention of the le- , gislator and the politician even more imperatively than of the eco- nomist. We are not merely to determine in what manner our corn- \ mercial operations in that vast peninsula may be most successfully I carried on, but by what means the welfare and liberties of one hun- dred millions of people, differing from ourselves in habits and institu- tions and religion, even more than in complexion, may be most effec- tually served.; how far those forms of procedure and those checks of 1 opinion, our Juriesand our press, may be rendered available on the Ganges for the same purposes as they are on the Thames; in a word, I bow the superior wisdom and policy of Europe can be copied out in Asia, with a view not to the pecuniary benefit of one nation, but to the j , i oint advantage of two great integral portions of a mighty empire. I It is quite evident, that before a satisfactory conclusion can be come to on a complicated question like this, so many facts are to be inves- itigated, so many opposing arguments are to be balanced, that not one committee, nor one session, nor one parliament, but many, may elapse. On the side of China, there is no such extended considerations, no such complexity of interests, and, what is of most importance, no such awful- ness of responsibility, to prevent us from coming to a speedy judgment. One false step with respect to India might be attended with conse- quences which no subsequent course of right would enable us to re- dress. If the simplicity of the China question should seduce us into a precipitate conclusion, the error would neither be deeply injurious nor irremediable. In China, we—or, to speak, more strictly, the East India Company—are a mere nompany of merchants, trading to the best advantage they can with a nation of foreigners. They have no claims on the Chinese, nor can they expect any concessions from them which the interest of the latter may not dispose them to yield. Were India torn from the sway of England, or were it annihilated, the ques- tion of the tea trade would remain unchanged. We therefore most certainly regret that the suggestion of Mr. BARING was not acted on in the appointment of the Committee, which we have noticed else- where, and that two committees were not appointed. At the same time, the number of the Committee is favourable to division of labour; and we hope the number will not be rendered unavailing, either from the non-attendance of the members, or from any idle Parliamentary form. If of the thirty-three, three sub-committees were formed—one for the tea trade, and the other two for separate departments of the India question properly so called—we might expect, not unreason- ably, at least a partial report before the session terminates. With the China question, a committee should be careful not to mix up, as has hitherto been done, considerations which have no essential connexion with it. A critic in the Quarterly Review, who, from the authoritative tone in which he speaks, we suppose we must look on as the Company's organ, has two objections to the opening of the China trade, (one of which he dwells on as earnestly as if it had never been ,heard of ,before,) which, when properly considered, come under this description. In the first place, if we open the trade, we are told we must make up our minds to the payment of the divi- dends on East India Stock, as well as several other payments con- nected with the machinery of the East India Government. Now we might observe, that it is by no means obvious that the people of England must pay the debts contracted in extending and consolidat- ing the Company's power in India, as a bribe for the opening of the trade to China, where the Company have no debts at all. But, even were this as indisputable as the writer seems to suppose, the plain answer would still be forthcoming,—if these dividends and charges are defrayed at present by the profits of the China trade, we shall not be in any worse condition in that respect under the free trade than the monopoly system. The other argument, and that on which the writer appears most to rely, is the real or fancied imprac- ticability of the Chinese political character. It seems that the Chi- nese are, notwithstanding their admitted sagacity, so very singular a people, that no motives of self-interest have the slightest weight with them ; that the passions and appetites which influence other fea- therless bipeds are inoperative in the Celestial Kingdom ; that they care nothing (not about commerce, for that we can believe, but) about the profits of commerce; that their sales and purchases are not regulated by their wants, as other men's are, but by certain capir- cious rules, which none but a company, or rather, none but the Com- pany, can either understand or apply. That the Chinese are very much inclined to picarooning, has been long known ; but it is a pecu- liarity in their roguery, that it imposes much more easily and sue- cessfully on individuals whose eyes may be supposed sharpened by something of an analogous feeling, than on the agents of a great trading corporation, whose personal interest is but remotely interested in its discovery. We confess we are slow to believe that human nature is so very different in the Eastern extremity of Asia, from what we find it in all other places, and under every possible shade of civilization. We have moreover seen it often, and, as appeared to us, with much show of reason, stated, that one grand cause why so many difficulties were interposed by the Chinese officiaries, in our dealings with them, was their jealousy of the Company ; that the greatness of their customers, so far from insuring superior ad- vantages, was in reality the cause why the Government was so trouble- some and so exacting ; and that, had the Company in India, as in China, continued to retain their original rank of a mere corporation. - of traders, those facilities would long ago have been granted to their weakness, which by a policy of which we cannot wholly disapprove, have been denied, to their power. But, granting that nothing save a show of importance can induce the Chinese to listen to the dictates of obvious self-interest, will it be asserted that the character of a British consul does not carry with it as much weight and dignity as that of the Company's head factor ?—that the representative of the King of England will not be as much reverenced, by the strangely-constituted minds of these ingenious people, as the representative of the gentle- men of Leadenhall Street ? And what is there to prevent the appoint, ment of such an officer ; or rather, is not such an appointment'ne- cessarily involved in the opening of the trade ? Laying aside, therefore, - these objections, which are mere matters of detail, and have no con- nexion with the inquiry which the Committee are about to pro- • secute, we shall in a very few words state what it is of importance that they should ascertain. First of all, there is the matter of fact respecting the prices of dif- ferent kinds of tea in Canton, in England, on the Continent of Europe, and in America. These will be obtained from the papers to be fur- nished by Government. We should hardly have alluded to them until the papers were in our hands, had it not been for a parade of• documentary evidence put forth by the writer in the Quarterly Re- view. He gives the price of a pound of Hyson at the Company's sales, as 4s. 4d. ; and then follows a statement' of the price of the same tea at New York, which is 4s. 6d. to 6s. 2d. Now the price of Hy-son is strangely selected as an example, for the proportion which the quantity sold of that peculiar kind of tea bears to the Black teas in common use is so small (we believe about 1 to 40) that no rule can be founded on it. But the example is useless in another respect, in- asmuch as the comparison attempted to be made is between tea with- -out duty in England and tea with duty in New York. To make the comparison fairly, we must deduct the duty in both cases • and this will give 3s. 8d. as the average price in New York,—an advantage of 131 per cent. If this were all, we might still ask, why should the people of England be overcharged even to that amount ? but, as we have already observed, no rule can be drawn from the price of Hyson, much less from the price when quoted in this way. In 1822' the price of Hyson (4s. .514.) in the London market was 2s. higher than at New York and Hamburg. That it had risen so much at the for- , mer place in 1827, must be attributed to accidental causes ; it ' evidently cost no more in China in the one year than the other. In 1822, also, the differences between the prices of the three great staple teas, namely, Bohea, Congou, and Twankay, in the London ' market, and at New York and Hamburg, were is. 8d., is. 6d., and is. 10d. respectively. To what were the enormous differences to be attributed, but to the monopoly of the Company ?—We do not, how- ever, wish to press this view of the subject, because the documents alluded to by 1111r. PEEL will furnish us with more ample, if not more unexceptionable Materials, and because we shall recur to the subject next week.

But there is a point of more importance than the mere fact of the prices Of tea, which the Committee must endeavour to ascertain. They must inquire, not only how far the monopoly Of the Company ac- tually raises the price of the commodity in England, but also how far the existence of such a monopoly tends to keep up prices in China also. We know it has been repeatedly asserted, and the assertion has hitherto gone for proof, that it is impossible to deal with the Chinese unless through the medium of the security merchants. We do not pretend on this, or indeed on any other point connected with this important inquiry, unless where we are borne out by documents, to speak dog- matically. What we wish to see, is such an impartial and thorough inquiry as shall satisfy—not the East India Directors—not the Petitioners for free trade, many of whom entertain very false and very foolish notions respecting its advantages—but the moderate and sen- sible part of the people of England. Now, on the subject of the Hong merchants, one observation will not fail to suggest itself to the Committee, namely, that so long s.s the monopoly continues, we cannot expect that any effort will be made to get rid of their inter- ference. We do not say that under a free trade we should get rid of - it, but unquestionably we should try. There is another point to which the Committee may properly direct their inquiries. It is well known that the Chinese are in the habit of , trafficking very extensively to the islands of the Eastern _Archipelago. At present we can take no advantage of that circumstance, to the supply of our wants either of tea or of any thing else. But if , the trade were free, might we not expect that the Chinese themselves would gladly take advantage of entrepots to supply us with whatever., the soil of China produces ? The whole argument derifed from the jealous and narrow-minded character of the Chineae Government is founded xi the assumption, that unless we trade7with the Chinese directly, we cannot trade with them at all, It is not a sufficient answer to this, that the Americans and others like ourselves trade only to Canton. We are the great exemplars in this as in many things—we lead the fashion in our follies as well as in our wisdom. Before we close this somewhat rambling article, we must men- tion one fact, strongly indicative of the spirit which animates the partisans of the Company. By the Commutation Act of 1784, cer- tain regulations were imposed on the Company touching the number of sales, and the prices at which the different teas are to be put in. This act, however, was of small value as a check on the rapacity of the Company, compared with the 18th Geo. II. cap. 26, by which the Lords of the Treasurpwere empowered, whenever the teas of the Company were not sufficient to answer the demand, or higher in price than on the Continent, to grant licences for the importation of teas from the Continent. Nothing could be conceived in a better spirit than the latter act ; nor, had it been kept in proper working, could any engine even of free trade have proved more effectual for the check- ing of the natural tendency of the Company to an artificial enhance- ment of the price of teas. W:Y1 our readers believe it, this salutary act has been repealed ; a17..o repealed how ?—by a clause surrepti- tiously foisted into the (*.Alston:is Consolidation Act ! So that there Is now no control v:'natever on the Company. They may import a large or a small quantity of tea, precisely as suits their convenience, and without 7.Eference either to demand or price. Mr. Huskisson was a member (Jf the Governmentwhen the law was altered. Perhaps he aaa,exP1Aain why it was altered, for the enlightenment of his Liver- Pow roOnstituents, and his other allies and clients: the petitioners for an Open trade.

Previous page

Previous page