PLURALISM FOR THE HELL OF IT

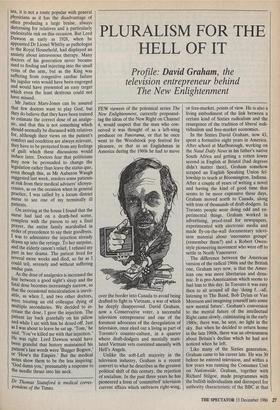

Profile.- David Graham, the

television entrepreneur behind The New Enlightenment

FEW viewers of the polemical series The New Enlightenment, currently propound- ing the ideas of the New Right on Channel 4, would suspect that the man who con- ceived it was thought of as a left-wing producer on Panorama, or that he once went to the Woodstock pop festival for pleasure, or that as an Englishman in America during the 1960s he had to move over the border into Canada to avoid being drafted to fight in Vietnam, a war of which he deeply disapproved. David Graham, now a Conservative voter, a successful television entrepreneur and one of the foremost advocates of the deregulation of television, once eked out a living as part of Toronto's counter-culture, in a quarter where draft-dodgers and mentally muti- lated Vietnam vets coexisted uneasily with Hell's Angels.

Unlike the soft-Left majority in the television industry, Graham is a recent convert to what he describes as the greatest political shift of this century, the rejection of socialism. In the past three years he has pioneered a form of 'committed' television current affairs which embraces right-wing, or free-market, points of view. He is also a living embodiment of the link between a certain kind of Sixties radicalism and the resurgence of the tradition of liberal indi- vidualism and free-market economics.

In the Sixties David Graham, now 43, spent a formative eight years in America. After school at Marlborough, working on the Natal Daily News in his father's native South Africa and getting a rotten lower second in English at Bristol (bad degrees didn't matter then), Graham somehow scraped an English Speaking Union fel- lowship to teach at Bloomington, Indiana. After a couple of years of writing a novel and having the kind of good time that seems to be more expensive these days, Graham moved north to Canada, along with tens of thousands of draft-dodgers. In Toronto people were doing odd and ex- perimental things. Graham worked in advertising, proof-read for newspapers, experimented with electronic media and made fly-on-the-wall documentary televi- sion material about 'encounter groups' (remember them?) and a Robert Owen- style pioneering movement who were off to settle in North Vancouver.

The difference between the American version of the radical 1960s and the British one, Graham says now, is that the Amer- ican one was more libertarian and dyna- mic. It is pro-Americanism which seems to fuel him to this day. In Toronto it was easy then to sit around all day 'doing f...-all, listening to The Band, Bob Dylan or Van Morrison and imagining yourself into some new mental future'. Graham's conversion to the mental future of the intellectual Right came slowly, culminating in the early 1980s; there was, he says, no light in the sky. But when he decided to return home in the late 1960s, there was an obviousness about Britain's decline which he had not noticed when he left.

Like many of the Sixties generation, Graham came to his career late. He was 30 before he entered television, and within a few years was running the Consumer Unit on Nationwide. Graham, together with Richard Stilgoe, made programmes with the bullish individualism and disrespect for authority characteristic of the BBC at that happier time. They made one about the seven people who have statutory right of entry into your home. They ran graphics of the 'Buy British' house and the 'Buy Best' house. They inquired why British cars were 30th in the reliability table. Slowly, Gra- ham says, he began to realise that the relaxed freedoms he had been used to enjoying were only possible in a country unworried by decline. Previously if some- one's garden shed was leaking or they weren't feeling very well he would have recommended that they be given more money, more care, a social worker. Some time in the mid-1970s, he realised the party was over.

Graham hopped off to The Money Prog- ramme to indulge a new interest in wealth generation. Then, bored by the constraints of film, in 1976 he again took a year out to experiment, this time with video electro- nics, both computer graphics and editing. Graham adores technology, and technolo- gy is the key to making current affairs programmes cheaply, without a studio, as Diverse Production, the company he founded with his partner Peter Donebauer, does today.

This was a mental breakthrough, but not yet a profitable one. Graham went back to BBC current affairs, to Panorama. It was there that his eventual conversion to the ideas of classical liberalism came about. At the end of the 1970s, as he describes in the introduction to the book of The New Enlightenment which he wrote jointly with Peter Clark, he was making a programme about the long-term unemployed on a grim Clydeside estate. He found himself think- ing that the only men who retained any dignity were the ones doing undeclared, black-market work, and not relying on the benevolence of the state. Colleagues were surprised that he rehearsed some current Conservative thinking about the poverty trap in his programme.

Today Graham is affectionate towards the BBC but highly critical of what he calls its misguided impression that it is balanced and objective. He calls it 'a socialist enclave in a capitalist society'. He thinks its programmes are good, and cheap com- pared with ITV, but that it doesn't really belong in the latter part of the 20th century.

His current belief in deregulation has been much misunderstood, most recently and unfairly in a BBC programme on television deregulation in Italy. While Graham is all in favour of disbanding the bureaucracies of BBC and ITV, he still believes in retaining some of the con- straints of public service broadcasting. Incidentally he seems almost singlehanded- ly to have convinced Mrs Thatcher that British television must have a 25 per cent quota from independent producers.

Graham's baptism as an entrepreneur was starting up a company to make alterna- tive current affairs programmes for Chan- nel 4. Diverse Production is the only independent current affairs company to have survived from the chaotic first year of Channel 4. At first they made the shambo- lic The Friday Alternative. This was re- placed by Diverse Reports, with a brief to include a roughly 50-50 mix of left-wing and right-wing programmes. They have done, for example, a sympathetic treat- ment of the hippies of Salisbury Plain, and an outright attack on the hard Left in the anti-racist movement. Diverse Production, at its offices near Olympia, now has a left-wing newsroom and a right-wing news- room, separated by the management to prevent overflows of temper. You notice that everyone in the place is unusually conversant with ideologies. The New Enlightenment, subtitled 'The rebirth of liberalism', is David Graham's brainchild. It sets out the ideas of Frederick Hayek, Milton Friedman, Irving Kristol and Lord Bauer. To many circles in the Conservative Party, Mrs Thatcher's in particular, those ideas are scarcely un- familiar, but no one has yet made a television series about them. Indeed the very idea of right-wing television was until recently a contradiction in terms. As televi- sion The New Enlightenment is close to outright polemic, which can be unsettling even if you agree with it. It has certainly ruffled feathers. Channel 4 has been deluged with complaints from viewers. After an unfavourable reception from the critics it now makes the 'Pick of the Day' section in the Guardian. There was even a whiff of scandal when it was discovered that The New Enlightenment received funding from the American liberal-right Reason Foundation as well as Channel 4. But the IBA decided that all was well under the Broadcasting Act, which forbids funding from non- broadcasting agencies except in special circumstances.

In a sense the title of David Graham's series describes his own path to enlighten- ment. He is reluctant to admit that he has been a bit of an intellectual butterfly, he prefers to say that he thinks his ideas will move on. When pressed on a point like what he now feels about the Vietnam war, he suspects he still thinks it was fought the wrong way, for the wrong reasons and at the wrong time. He has problems still about foreign policy. It is reasonably easy to take Graham at his own assessment, as a television entrep- reneur interested in the quality of political debate in the medium. Diverse Produc- tion, in those terms, is a sort of anarcho- capitalist Marxism Today, prepared to give an airing to most points of view for the sheer hell of it. Graham would like Diverse now to make a good left-wing series. This week he is in Moscow, trying to set up a joint British-Russian news discussion prog- ramme. Before he went he said he was taken with the idea's novelty — and its deep unlikeliness.

it was full of architects.'

Previous page

Previous page