Photography

War graves

Gavin Stamp

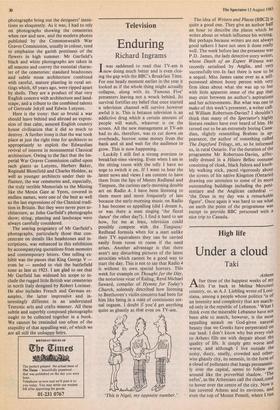

Tohn Garfield is a consultant neuro- surgeon at Southampton Hospital. He is also a very good photographer — as good as any professional — and a selection of his own beautifully finished prints has recently been seen at the Camden Arts Centre. Visitors may, indeed should, have found them depressing, for they are all of the cemeteries of the Great War, which are mostly to be found in France and Belgium. They are emotional and powerful photographs, for Mr Garfield is one of those who is rightly obsessed by the catastrophe to civilisation which the first world war was, and in the cemeteries he finds that 'it is the poignancy, solitude and sense of futility which forces itself on one'. I wish I had known Mr Garfield six years ago when I organised an exhibition about the memorial and cemetery architecture of the Great War, called Silent Cities, for his

photographs bring out the designers' inten- tions so eloquently. As it was, I had to rely on photographs showing the cemeteries when raw and new, and the modern photos published by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, usually in colour, tend to emphasise the garish prettiness of the flowers in high summer. Mr Garfield's black and white photographs are taken in all seasons and convey the essential charac- ter of the cemeteries: standard headstones and subtle stone architecture combined with careful, mature planting in rural set- tings which, 65 years ago, were ripped apart by shells. They are a product of that very English concern with architecture and land- scape, and a tribute to the combined talents of Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens.

Here is the irony: that so brutal a war should leave behind and abroad an expres- sion of that calm, assured English country house civilisation that it did so much to destroy. A further irony is that the war took place at just the right time for architects so appropriately to exploit the Edwardian revival of interest in monumental Classical architecture. Owing to the fact that the Im- perial War Graves Commission called upon such giants as Lutyens, Herbert Baker, Reginald Blomfield and Charles Holden, as well as younger architects under their in- fluence, the war cemeteries and, especially, the truly terrible Memorials to the Missing like the Menin Gate at Ypres, covered in endless names, were one of the best as well as the last expressions of the Classical tradi- tion in Britain. But they were never pure ar- chitecture, as John Garfield's photographs show; siting, planting and landscape were always carefully considered.

The searing poignancy of Mr Garfield's photographs, particularly those that con- centrate on details like headstones and in- scriptions, was enhanced in this exhibition by accompanying quotations from memoirs and contemporary letters. One telling ex- hibit was the passes that King George V even he — needed to visit the battlefield zone as late as 1923. I am glad to see that Mr Garfield has widened his scope to in- clude the rugged little British war cemeteries in north Italy designed by Robert Lorimer. He also includes French and German ex- amples, the latter impressive and in- terestingly different in an understated Teutonic arts and crafts manner. All these subtle and superbly composed photographs ought to be collected together in a book. We cannot be reminded too often of the stupidity of that appalling war, of which we are all still the unhappy heirs.

Previous page

Previous page