ARTS

Exhibitions

Anthony Eyton (Browse & Darby, till 27 April)

Eyton's loud exclamations

Andrew Lambirth explores the two sides of Anthony Eyton's paintings Aithony Eyton, now in his 73rd year, is painting better and better. This immensely enjoyable exhibition of his paintings done over the last four years separates the work neatly into two: all the pictures in the ground floor gallery were painted in the studio, all those downstairs were done in front of the motif. A difference is immedi- ately discernible, for Eyton's studio prac- tice of reconstructing a scene from sketches made on the spot, from memory and some- times from photographs, involves also a leavening of imagination. The closely- worked picture surface, though pulled together into a conscious whole, has a delightful formal freedom to it. In other words, the gesture made in pastel or oil has slightly more to do with how it looks as a dab of colour or as a shape on the picture plane, than as a straightforward record of something seen. Thus it can be experimen- tal and not merely representational. There is perhaps more deliberation to a studio picture, but there need be no loss of vitali- ty. By contrast, the pictures done in front of the subject are a direct visual transcrip- tion, more instinctual in approach, focusing on details rather than the overall effect. This gives them a pleasing immediacy. The two approaches are complementary rather than exclusive.

Eyton appears to belong to an earlier tradition than the Euston Road School with which he is usually associated. There is more than a touch of Impressionism here, but the squaring up in the finished painting indicates that he is by no means dependent on method. It is particularly evi- dent in his huge Indian composition, `LuIcki Gate, Bannu Market'. He obviously feels comfortable using this kind of scaf- folding, and has no need to disguise it. This honesty is appealing, while the sporadic presence of the grid controls and to some extent rationalises Eyton's innate Romanti- cism and makes the picture believable.

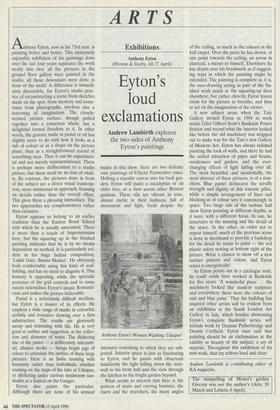

Pastel is a notoriously difficult medium, but Eyton is a master of its effects. He employs a wide range of marks in colourful, scribbly and evocative drawing over a firm substructure. The results are gloriously messy and brimming with life. He is very good at outline and suggestion, at the reflec- tion and shimmer of water. The flickering line of the pastel — a deliberately intermitt- tef, allusive stroke — brings bright jags of colour to articulate the surface of these large pictures. Here is an India teeming with humanity rather than individuals, whether washing on the steps of the lake at Udaipur, or sheltering under curious mushroom sun- shades at a festival on the Ganges.

Eyton also paints the particular. Although there are none of his sensual nudes in this show, there are two delicate vase paintings of Felicite Parmentier roses. Hefting a sizeable canvas into his back gar- den, Eyton will paint a eucalyptus or an elder tree, or a view across other Brixton gardens. These oils are vibrant in tone, almost exotic in their lushness, full of movement and light, fresh despite the intensive reworking to which they are sub- jected. Interior space is just as fascinating to Eyton, and he paints with observant familiarity the light falling down the stair- well to his front hall and the view through the kitchen to the bright garden beyond.

What seems to interest him here is the pattern of stairs and curving banister, the risers and the stretchers, the many angles Anthony Eyton's 'Women Washing, Udaipur' of the ceiling, as much as the colours in the hall carpet. Over the paint he has drawn, at one point towards the ceiling, an arrow in charcoal, a memo to himself. Elsewhere he has drawn over his brushwork as if suggest- ing ways in which the painting might be extended. The painting is complete as it is, the over-drawing acting as part of the fin- ished work much as the squaring-up does elsewhere, but rather cleverly Eyton leaves room for the picture to breathe, and thus to act on the imagination of the viewer.

A new subject arose when the Tate Gallery invited Eyton in 1994 to work inside Giles Gilbert Scott's Bankside Power Station and record what the interior looked like before the old machinery was stripped out to make way for the Tate's new Gallery of Modern Art. Eyton has always relished painting the look of walls, and there he had the added attraction of pipes and beams, condensers and girders, and the ever- changing effects of light falling over all. The most beautiful, and incidentally, the most abstract of these pictures, is of a stan- chion. Blue pastel delineates the scruffy strength and dignity of this totemic pillar, while a simple arrangement of lines and blocking-in of colour sets it convincingly in space. Two large oils of the turbine hall show Eyton painting at different depths, as it were, with a different focus. In one, he luxuriates in the massing and the detail of the space. In the other, in order not to repeat himself, much of the previous scene is done in shorthand to provide a backdrop for the detail he wants to paint — the red plastic safety netting at bottom right of the picture. What a chance to show off a new surface pattern and colour, and Eyton seizes it energetically!

As Eyton points out in a catalogue note, he could easily have worked at Bankside for five years: 'A wonderful place . . . the machinery looked like modern sculpture and everywhere there were the colours of rust and blue paint.' That the building has inspired other artists will be evident from an exhibition at the South London Art Gallery in July, which besides showcasing Eyton's complete Bankside series, will include work by Deanna Petherbridge and Dennis Creffield. Eyton once said that painting should be an exclamation at the validity or beauty of the subject, a cry of surprise. Throughout this exhibition of his new work, that cry echoes loud and clear.

Andrew Lambirth is contributing editor of RA magazine.

The misspelling of Monet's garden Giverny was not the author's (Arts, 30 March and Letters, 6 April).

Previous page

Previous page