WHO'S MR NO? IT'S MR SMITH

We can thank him, says Sophie Barker,

if we are still paying for our pints in pounds in 2004

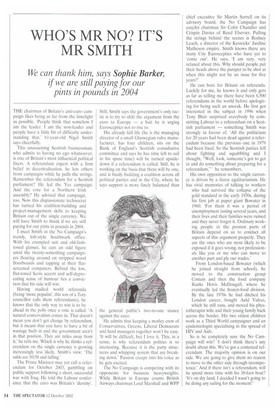

THE chairman of Britain's anti-euro campaign likes being as far from the limelight as possible. 'People think that somehow I am the leader. I am the non-leader and people have a little bit of difficulty understanding that,' 61-year-old Nigel Smith says cheerfully.

This unassuming Scottish businessman, who admits to having no ego whatsoever, is one of Britain's most influential political fixers. A referendum expert with a firm belief in decentralisation, he lets others front campaigns while he pulls the strings. Remember the referendum for a Scottish parliament? He led the Yes campaign.

And the vote for a Northern Irish assembly? He advised that campaign, too, Now this dispassionate technocrat has turned his coalition-building and project-management skills to keeping Britain out of the single currency. We will have Smith to thank if we are still paying for our pints in pounds in 2004.

I meet Smith in the No Campaign's trendy, loft-style Southwark office.

With his crumpled suit and old-fash ioned glasses, he cuts an odd figure amid the twenty-something campaign ers floating around on stripped wood floorboards and tapping at their flatscreened computers. Behind the low, flat-toned Scots accent and self-deprecating sense of humour lies a conviction that his side will win.

Having studied world referenda (being 'more populist', this son of a Tory councillor calls them referendums), he knows that the only way to win is to be ahead in the polls once a vote is called. 'A natural conservatism comes in. That doesn't mean you don't get change by referendum, but it means that you have to have a bit of wastage built in and the government aren't in that position. They are miles away from it,' he tells me. Which is why he thinks a referendum on the single currency is growing increasingly less likely. Smith's view: 'The odds are 50:50 and falling.'

The Prime Minister may yet call a referendum for October 2003, gambling on public support following a short, successful war with Iraq. He told the Labour conference that the euro was Britain's 'destiny'.

Still, Smith says the government's only tactic is to try to shift the argument from the euro to Europe — a bait he is urging Eurosceptics not to rise to.

His already full life (he is the managing director of a small Glaswegian valve manufacturer, has four children, sits on the Bank of England's Scottish consultative committee and says he has time left to sail in his spare time) will be turned upsidedown if a referendum is called. Still, he is working on the basis that there will be one, and is busily building a coalition across all political parties and in the City, where he says support is more finely balanced than

the general public's two-to-one stance against the euro.

He admits that keeping a motley crew of Conservatives, Greens, Liberal Democrats and fund managers together won't be easy. 'It will be difficult, but I love it. This, in a sense, is why referendum politics is so interesting. Because it is the party structures and whipping system that are breaking down.' Passion creeps into his voice as he gets excited.

The No Campaign is competing with its opponents for business heavyweights. While Britain in Europe counts British Airways chairman Lord Marshall and WPP

chief executive Sir Martin Sorrell on its advisory board, the No Campaign has easyJet chairman Sir Colin Chandler and Crispin Davies of Reed Elsevier. Pulling the strings behind the scenes is Rodney Leach, a director of the Keswicks' Jardine Matheson empire. Smith knows there are many City Eurosceptics who have yet to 'come out'. He says, 'I am very, very relaxed about this. Why should people put their heads above the parapet to be shot at when this might not be an issue for five years?'

He can bore for Britain on referenda. Luckily for me, he knows it and only gets as far as telling me there have been 6,500 referendums in the world before apologising for being such an anorak. He first got interested in the subject in 1996 when Tony Blair surprised everybody by committing Labour to a referendum on a Scottish parliament — something Smith was strongly in favour of. 'All the politicians for 20 years had been dead against a referendum because the previous one in 1979 had been fixed. So the Scottish parties fell about fighting and squabbling and I thought, "Well, look, someone's got to get in and do something about preparing for a referendum,"' he remembers.

His own opposition to the single curren cy is driven by a fierce egalitarianism. He has vivid memories of talking to workers who had survived the collapse of the gold standard in the early 1930s, during his first job at paper giant Bowater in 1960. 'For them it was a period of unemployment lasting several years, and their lives and their families were ruined and they never forgot it. Ordinary working people in the poorest parts of Britain depend on us to conduct all aspects of this argument properly. They are the ones who are most likely to be exposed if it goes wrong, not professionals like you or me who can move to another part and ply our trades.'

From London-based Bowater (which he joined straight from school), he moved to the construction group Costain and then the food company Ranks Hovis McDougall, where he eventually led the frozen-food division. By the late 1970s he had ditched his London career, bought Auld Valves, which he still runs, and moved his phys iotherapist wife and their young family back across the border. His two oldest children work as a Third World campaigner and an

epidemiologist specialising in the spread of

HIV and Aids.

So is he completely sure the No Campaign will win? 'I don't think there's any doubt about this. We've got a contested referendum. The majority opinion is on our side. We are going to give them no reason to move to the other side through incompetence.' And if there isn't a referendum, will he spend more time with his 38-foot boat? It's on dry land. I decided I wasn't going to be doing any sailing for the moment!'

Previous page

Previous page