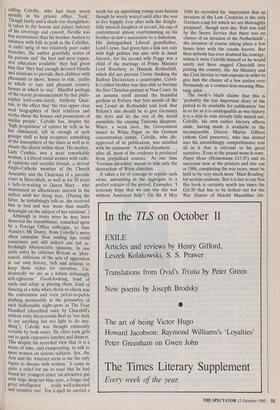

Beyond the fringes

Alastair Forbes

THE FRINGES OF POWER: DOWNING STREET DIARIES 1939-1955 by John Colville

Hodder & Stoughton, f14.95

In one of the baker's half-dozen of the books already to his credit, Sir Jock (no- body beyond the font seems ever to have called him John) Colville first described how, as an egregious fledgling diplomat, he had from a Foreign Office balcony enthu- siastically cheered Neville Chamberlain's proclamation, from a Downing Street up- per window, of his brazen betrayal of the Czechs as 'Peace with honour' until shamed into silence by a wiser and more sophisticated superior, Sir Orme. Sargent. Little more than a year and a half later, at the very moment Winston Churchill was at Buckingham Palace being invited by a far from enthusiastic King George VI to form a National Coalition Government, he walked across the street in the opposite direction with Alec Home (then Dunglass) and joined, in the Under-Secretary of State's room, Rab Butler and Chips Chan- non in drinking in champagne 'the health of the "King over the Water" [Mr Cham- berlain]'. Eschewing discretion as he did all his life, Rab said

he thought the good clean tradition of English politics . . . had been sold to the greatest adventurer of modern political his- tory . . . a half-breed American whose main support was that of inefficient but talkative people of a similar type.

Earlier the same day, in the diary Col- ville had decided at the beginning of the war to keep in defiance of every existing rule, regulation and order (any Soviet bureaucrat tempted to pursue such a hob- by, so I am informed by an authoritative Muscovite source, would if caught be shot out of hand), he had written of 'the terrible risk' of putting Churchill at the helm, adding that, as a result, I cannot help fearing that this country may be manoeuvred into the most dangerous position it has ever been in . . . Everybody at No. 10 is in despair at the prospect. Personally I shall be sorry too, because I feel a greater loyalty to the PM than I had supposed.

Chamberlain, whom Churchill was later to call 'the narrowest, most ignorant, most ungenerous of men' who 'knows not the first thing about war, Europe or foreign politics', had only the week before taken to calling Colville, who had been seven months in his private office, 'Jock'. Though lately and a shade too thoughtless- ly taken to the bosom and palace balcony of his sovereign and consort, Neville was less accustomed than his brother Austen to intimacy with folk as posh as the Colvilles. A cadet sprig of two relatively poor cadet branches, the author gratefully writes of his parents and 'the best and most expen- sive education available' they had given him that 'they had enough devoted friends and relations to provide their children with pheasants to shoot, horses to ride, yachts in which to race and pleasant country houses in which to stay'. Mindful perhaps of the recent pronouncement by that philo- sopher lord-come-lately, Anthony Quin- ton, to the effect that `the true upper class read biographies of their relations and works about the houses and possessions of similar people', Colville has, despite the `high proportion' of entries he tells us he has eliminated, left in enough of such gossipy stuff to help recapture something of the atmosphere of the times as well as to situate the diarist within them. His mother, Lady Cynthia, was a most remarkable woman, a Liberal social worker with radic- al opinions and socialist friends, a devout Anglo-Catholic member of the Church Assembly and the Chairman of a juvenile court in Shoreditch, as well as for 30 years a lady-in-waiting to Queen Mary — who maintained an affectionate interest in the author until her dying days. (During the latter, he tantalisingly tells us, she received him in bed and was 'more than usually downright on the subject of her relations'.) Although in many ways he may have deserved the resemblance, remarked upon by a Foreign Office colleague, to Jane Austen's Mr Darcy, from Colville's more often saturnine than smiling lips could sometimes and still indeed can fall re- freshingly idiosyncratic opinions. In one early entry he criticises Britons as 'phar- isaical, oblivious of the acts of aggression in our own history, rich and anxious to keep those riches for ourselves. Un- doubtedly we are as a nation irritatingly self-righteous.' Good-looking, fond of cards and adept at playing them, fond of dancing at a time when cheek-to-cheek was the convention and even pelvis-to-pelvis pushing permissible in the penumbra of such fashionable night-spots as The Four Hundred (described once by Churchill's seldom witty ducal cousin Bert as 'too dark to see anything but too light to do any- thing'), Colville was thought eminently sortable by both sexes. He often took girls out to quite expensive lunches and dinners. This despite his recorded view that 'it is a waste of time, and exasperating, to talk to most women on serious subjects. Sex, the Arts and the Abstract seem to me the only topics to discuss with women.' It came as quite a relief for me to read that he had found my youngest sister 'an attractive girl with large deep-set blue eyes, a fringe and great intelligence . . . really well-educated and sensitive too'. For a spell he carried a torch for an appetising young near-heiress though he wisely waited until after the war to live happily ever after with the delight- fully musical daughter of an earl, his cup of contentment almost overbrimming on his brother-in-law's succession to a dukedom. His distinguished Liberal grandfather, Lord Crewe, had given him a link not only with high politics but also with la haute Juiverie, for his second wife Peggy was a child of the marriage of Prime Minister Lord Rosebery to Hannah Rothschild, which did not prevent Crewe thinking the Balfour Declaration a catastrophe. Colvil- le's eldest brother was thus able to become the first Christian partner at New Court. In an autumn stroll around the beautiful gardens at Exbury that first month of the war Lionel de Rothschild told Jock that Britain's aim should be to give Germany the Jews and let the rest, of the world assimilate the ensuing Teutonic diaspora. When, a week later, the Government issued its White Paper on the German concentration camps, Colville, who dis- approved of its publication, was satisfied with the comment: 'A sordid document . . . after all, most of the evidence is produced from prejudiced sources.' At one time `German atrocities' meant to him only the destruction of Wren churches.

It takes a lot of courage to reprint such views, amounting in the aggregate to a perfect sottisier of the period. Examples: 'I seriously hope that we can win this war without American help'! On the 8 May 1940 he recorded his 'impression that an invasion of the Low Countries is the only German coup for which we are thoroughly prepared', though next day 'Rai) was told , by the Secret Service that there was no chance of an invasion of the Netherlands', the invasion of course taking place a few hours later with the results known. But then nobody has ever doubted his courage, unless it were Colville himself or he would surely not have nagged Churchill into putting the country, the Air Ministry and the Civil Service to vast expense in order to give him the chance of a few sorties over Normandy as a contact-lens-wearing Mus- tang pilot.

The book's blurb claims that this is `probably the last important diary of the period to be available for publication' but in so far as it is cataloguable as war history it is a déjà lu vein already fully mined out, Colville, his own earlier literary efforts aside, having made it available to the incomparable Doctor Martin Gilbert (whom God preserve), who has slotted into his astonishingly comprehensive text all in it that is relevant to his great narrative. Even at the pound more it costs, Finest Hour (Heinemann £15.95) and its successor now at the printers and due out in 1986, completing the war years, must be held to be very much more 'Must Reading' for serious students. But it is fair to say that this book is certainly worth ten times the £18.50 that has to be forked out for the War Diaries of Harold Macmillan (de- scribed by Colville as 'finicky and insin- cere . . . I don't like the ingratiating way he bares his teeth') whose principal value is their revelation that Eden's paranoiac suspicion and dislike of him can be traced all the way back to 1943-44.

Long as his duty hours were, Colville was very far from seeing the full picture sometimes, like the oily and unethical Charles Moran getting only the fag-ends of midnight cigars. If he often found Chur- chill's reactions to external events and pressures unpredictable and illogical, it was in large part because neither he nor anyone else on the secretarial staff at No. 10 was every privy to the arcana that arrived every day, by hand of 'C' himself, in one of the immaculate buff dispatch-boxes, still embossed VRI, which had been unear- thed by the Foreign Office clerks for the benefit of the only 30 persons to whom Bonijace decrypts, the 'golden eggs' laid by the Ultra eggheads at Bletchley, were circulated. This was one other club to which Colville never secured election. But his several tributes to the man who was Chief of the Joint Intelligence Committee throughout the war gave me great plea- sure, for few men have done the State more service than Bill Cavendish-Bentinck (needless to say, yet another Colville kins- man). Today, as the nonagenarian last Duke of Portland, he is still as bright as the shiniest button and is the oldest man in the kingdom to be earning a salary in an important job — over and above all that lovely attendance lolly on tap down at the House of Lords.

Colville has interpolated into his diary a few pages brilliantly summing up, in tran- quil posthumous recollection, the many varied Churchillian qualities that, out- weighing the all too aggravating faults, caused him to surrender unconditionally to his disarmingly lovable new master and to forget the Munichite memories and nostal- gia for Neville Chamberlain that I myself thought so tiresome to have to listen to him declaiming as we drove together from Downing Street to Chequers one Friday afternoon in October 1940, an occasion on which his diary registered me as 'a slightly affected, opinionated and supercilious youth', with an added descriptive footnote for whose easily verifiable inaccuracy he has since courteously apologised to me in writing. A year later I am allowed to have `improved on acquaintance', and I am fortunately by no means alone in that. Mary Churchill Soames, to whom the book is affectionately and penitently dedicated, is variously described in the same period as `rather supercilious, captious and tiresome . . . a shade too prim'. The political views of her mother, who liked to tweak Jock's toffee nose sometimes, are found to be 'as ill-judged as they are decisive'. The 'cad' Bracken, the 'supremely unattractive' Lin- demann and the King's other bete noire, the 'utterly mischievous' Beaverbrook, (the latter making himself especially agree- able with corrupting gifts to Colville of valuable first editions) soon have their

horns transmogrified into haloes, albeit worn at rather rakish angles. Only Ran- dolph, 'one of the most objectionable people I have ever met', gets no reprieve.

To those who do not keep them, other people's diaries often serve as effective memory-joggers. Colville's account of the first weekend we spent in the same house (along with seven Churchills, five generals, two air marshals, one Admiral of the Fleet, Mr and Mrs Attlee and Professor Linde- mann) set total recall in motion, but I have total blank about another occasion a few months later, when there is said to have been 'a lot of flippant conversation about metaphysics, solipsists and higher mathematics' at the Chequers table, though I do believe I may that evening have tried to cheer up Lord Alanbrooke by telling him that Nostradamus had pre- dicted a long war about this time would be won by a man 'born in Pau', as he was. On 3 January 1944, Colville records from the Villa Taylor at Marrakech that 'the local French General and his wife' dined with the convalescent PM and his wife, daugh- ter, staff and guests. His date may be wrong, for he makes no mention of his reviewer breezing in after dinner having had no trouble at all driving up in a taxi to deliver a friendly greeting after the aircraft that I had supposed to be taking me back to the UK via Gibraltar from Algiers had got rerouted over the Atlas to Morocco, its passengers stuck to await movement on- ward in the next available Liberator bom- ber. It was Sir John Martin, Colville's superior, who, concealing any surprise he may have felt, bade me join the PM who hospitably plied me with whisky and ques- tions about de Gaulle, whose attitude I had found in Algiers (where I spent much time with a handsome young Frenchman from the Resistance called Francois Mitterrand, because we were both after the same pretty girl, Gaston Palewski's driver called, be- lieve it or not, 'France') to be much improved. Lord Beaverbrook seemed the only person present to be less than cosily chummy. Next morning Sarah Churchill called on me at the Mamounia to say that my impromptu drop-in had triggered a major security flap which, since I success- fully that evening boarded a Britain-bound bomber in which nothing worse happened to me than upsetting several dozen oranges on the head of an admiral who turned out to be Mrs Attlee's brother, I did not stay to witness. Later in London, Clemmie Chur- chill, smiling despite herself, gave me what she had intended to be a severely sardonic account of the matter, which included the arrest of the unfortunate French general and his wife invited for dinner.

More perfect techniques of secure cover- ups and cover-stories were to become very much Colville's speciality when, back in the saddle (or perhaps one should say howdah) once more in 1951, the old man recalled him from a resumed diplomatic career so that he could have about him a familiar, friendly and forgiving aide-de- camp ready at all hours to play backgam- mon with his wife and bezique with him- self. How often in wartime had Colville heard Winston's assurances that, come the end of hostilities, he would wash his hands for ever of party politics! But even by the time he had enjoyed a brief spell under Clement Attlee with dinner jackets once again de rigueur at Chequers, he had realised that, for Churchill, politics, which for him meant only power or its pursuit, had to be an adventure without end. Though he could observe and in his diary record that Churchill was by now pretty far over the hill, he remained loyal to him far beyond the call of a civil servant's duty. Since, some years ago, we crossed lengthy words on that and other Churchilliana in the correspondence columns of a Times which was then a newspaper with a smaller circulation but a larger influence, he has come to admit how close to the wind of unconstitutionality he sailed during the summer of 1953, with the cognisance of a sovereign whose private secretary he had been before her accession. Ferdinand Mount has lately written of the 'dignity' of the announcement this year of Mr Reagan's cancer, `so much more admirable than the seedy Tory Ministers hushing tiP Sir Winston's stroke in cahoots with the awful old Dr Moran'. The trouble was that they were not ministers but irresponsible press lords hand-picked by Colville and Christopher Soames (who himself became unconstitutionally privy to Cabinet pap- ers). Post hoc ergo propter hoc, it was inevitably argued that they were acting to keep the top place warm for Anthony Eden, sick in the American hospital to which he had been taken to save him from the incompetence of the accident-prone British medical profession. From the Un- ited States at the time I managed to slip into a cabled column an accurate sentence to the effect that in Washington Churchill's illness, causing the postponement of the Bermuda Conference, was 'regarded as a stroke of luck'. Though on my return to Fleet Street I encountered the censorship successfully engineered by Colville, I nevertheless thought it right to communi- cate a full report of what had happened, both medically and politically, to the Edens, who informed me by return that mine was the first account they had been given. Colville and Soames were of course already sure, rightly as it turned out, that Eden was unfit for the top job, but Winston, despite having developed 'a cold hatred' (Colville scripsit) of Eden, re- turned I may add with interest, could not make the late switch to Macmillan which the latter had himself proposed in a foolhardy typewritten letter to No. 10 re- turned to him without comment. Colville's finest hour came after Churchill's final resignation, so long deferred by desperate and unworthy cat-and-mousing, when he accompanied Winston, the star to which his waggon was still hitched, to Sicily and there offered to raise, through connections made more dazzling yet by his years at the fringes of power, the money • to create Churchill College, which might just as well be known as Colville's College. There these diaries have been lodged by their author, who, one feels, after accompany- ing him through the 700 pages of them, has, like so many of the persons therein described, much 'improved on acquai- nance'.

Previous page

Previous page