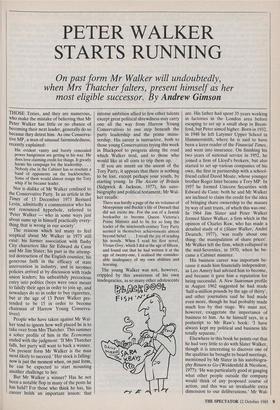

PETER WALKER STARTS RUNNING

On past form Mr Walker will undoubtedly, when Mrs Thatcher falters, present himself as her

most eligible successor. By Andrew Gimson THOSE Tories, and they are numerous, who make the mistake of believing that Mr Peter Walker has little or no chance of becoming their next leader, generally do so because they detest him. As one Conserva- tive MP, a man of unusual fairmindedness, recently explained:

His evident vanity and barely concealed power hungriness are getting in his way. He does love claiming credit for things. It greatly harms his campaign for the leadership. . . . Nobody else in the Cabinet has so resolute a band of opponents on the backbenches. Some of them would almost resign the Tory whip if he became leader.

Nor is dislike of Mr Walker confined to the Conservative Party. In an article in the Times of 13 December 1973 Bernard Levin, admittedly a commentator who has not renounced hyperbole, referred to `Peter Walker — who in some ways just about sums up in himself practically every- thing that is wrong in our society'. The reasons which led many to feel sceptical about Mr Walker in 1973 still exist: his former association with flashy City characters like Sir Edward du Cann and Mr Jim Slater; his part in the attemp- ted destruction of the English counties; his generous faith in the efficacy of state intervention in industry, and in incomes policies arrived at by discussion with trade union leaders; his unhealthily precocious entry into politics (boys were once meant to falsify their ages in order to join up, and nowadays do so in order to buy cigarettes, but at the age of 13 Peter Walker pre- tended to be 15 in order to become chairman of Harrow Young Conserva- tives).

People who have taken against Mr Wal- ker tend to ignore how well placed he is to take over from Mrs Thatcher. This summer a sober profile of him in the Economist ended with the judgment: 'If Mrs Thatcher falls, her party will want to back a winner. On present form Mr Walker is the man most likely to succeed.' Her stock is falling: now is just the moment when, on past form, he can be expected to start mounting another challenge to her.

But Mr Walker a winner? Has he not been a notable flop in many of the posts he has held? For those who think he has, his career holds an important lesson: that intense ambition allied to few other talents except great political shrewdness may carry one all the way from Harrow Young Conservatives to one step beneath the party leadership and the prime minis- tership. His career is instructive, both to those young Conservatives trying this week in Blackpool to progress along the road which Walker trod, and to those who would like at all costs to trip them up.

If you are intent on the ascent of the Tory Party, it appears that there is nothing to be lost, except perhaps your youth, by starting young. In The Ascent of Britain (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1977), his auto- biography and political testament, Mr Wal- ker recalls:

There was hardly a page of the six volumes of Monypenny and Buckle's life of Disraeli that did not excite me. For the son of a Jewish bookseller to become Queen Victoria's Prime Minister and to be for so long the leader of the nineteenth-century Tory Party seemed in themselves achievements almost beyond belief. . . I recall the joy of reading his novels. When I read his first novel, Vivian Grey, which I did at the age of fifteen, and found out that he had written it at the age of twenty-one, I realised the consider- able inadequacy of my own abilities and learning.

The young Walker was not, however, crippled by this awareness of his own inadequacies, as so many other adolescents are. His father had spent 35 years working in factories in the London area before escaping to set up a small shop in Brent- ford, but Peter aimed higher. Born in 1932, in 1948 he left Latymer Upper School in Hammersmith, where he is said to have been a keen reader of the Financial Times, and went into insurance. On finishing his two years of national service in 1952, he joined a firm of Lloyd's brokers, but also started to set up various companies of his own, the first in partnership with a school- friend called David Moate, whose younger brother Roger later became a Tory MP. In 1957 he formed Unicorn Securities with Edward du Cann: both he and Mr Walker are inclined to claim the credit for the idea of bringing share ownership to the masses by way of unit trusts, of which this was one. In 1964 Jim Slater and Peter Walker formed Slater Walker, a firm which in the opinion of Charles Raw, who has made a detailed study of it (Slater Walker, Andre Deutsch, 1977), 'was really about one thing: the manipulation of share prices'. Mr Walker left the firm, which collapsed in the mid-Seventies, in 1970, when he be- came a Cabinet minister.

His business career was important be- cause it made him financially independent, as Leo Amery had advised him to become, and because it gave him a reputation for being successful. A New Statesman profile in August 1962 suggested he had made `half-a-million pounds by the age of thirty', and other journalists said he had made even more, though he had probably made much less by that stage. We must not, however, exaggerate the importance of business to him. As he himself says, in a postscript to Mr Raw's book: 'I have always kept my political and business life totally separate.'

Elsewhere in this book he points out that he had very little to do with Slater Walker, though it is interesting to discover one of the qualities he brought to board meetings, mentioned by Mr Slater in his autobiogra- phy Return to Go (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977): 'He was particularly good at gauging what other people outside the company would think of any proposed course of action, and this was an invaluable extra dimension to our deliberations.' Mr Wal- ker always was a master of public relations.

Elected to the Commons in 1961 to sit for Worcester, he had already been awarded the MBE 'for political and public services' to Mr Macmillan and others. He had also visited the USA and got to know J.F.Kennedy. For both men he professes a very high regard. In 1963-64 he was par- liamentary private secretary to Mr Selwyn Lloyd, and in 1965 he became one of Mr Heath's campaign managers, having helped him fight that year's Finance Bill clause by clause. In June 1970 Mr Heath made him Minister of Housing and Local Government; in October 1970 he became the very first Secretary of State for the Environment. He was, of course, the youngest member of the Cabinet.

He shows no remorse for the changes to county boundaries, and the creation of the metropolitan counties, which he saw through Parliament, or none beyond con- ceding that he should have allowed less scope for local empire building by council- lors and bureaucrats. When he kindly allowed me an hour of his time last week, he revealed no hint of understanding for the feelings of 'your poor Mr Auberon Waugh who thought Somerset was des- troyed'. At the time, he recalled, there was a standing ovation for his proposals, the Cabinet, including the Secretary of State for Education, Mrs Margaret Thatcher, was united behind him, and in merging Hereford and Worcester, which led to trouble in his constituency, he committed `an act of political courage and bravery'. He also ought to be thanked for toning down Maud's original proposals. In other words, Mr Walker, unlike Sir Keith Joseph, is not inclined to renounce actions which have turned out to be disastrous. Anyone who can bear to be reminded how catastrophic was Mr Walker's reorganisa- tion of local government is referred to the Spectator of 6 October 1979, where Christ- opher Booker, Ferdinand Mount, Michael Wharton, Richard West and John Betje- man examine it in painful detail.

Mr Walker went on to be Secretary of State for Trade and Industry from 1972-74, his ministerial team including Mr Geoffrey Howe and Mr Michael Heseltine. He was a staunch supporter of Heath's 'U-turn'. Even before the 1970 election, 'together with Edward Boyle and Reggie Maudling I was the only member of the Shadow Cabinet opposed to not continuing with some form of Prices and Incomes policy' (Postscript to Raw). Last week he clarified his view on these matters by telling me that he had never been in favour of a prices policy. He would like a voluntary incomes policy, if only a reasonable union lead- ership could be brought to see the benefits of one. Mr Jones and Mr Scanlon had wrecked everything when Mr Heath tried to have one, by making highly inflationary wage demands, but agreement had nearly been reached.

Throughout his career, Mr Walker has remained faithful to the interventionist view of industrial policy. Government and

industry must work together to defeat foreign competition. 'We must find the dynamism to kick the economy into a higher growth gear,' he said on 2 May this year, but he might have said it at any time in the last 30 years. While at the DTI he began a 'massive' expansion of the steel industry (two of his favourite adjectives are `massive' and 'exciting'): 'Under my origin- al proposals by 1979 we would have had a steel capacity of between 33 and 35 million tons, and by the middle of the 1980s of up to 38 million tons' (The Ascent of Britain). Unfortunately the Labour government wrecked this plan, assisted by the world recession. Today Britain produces only 15 million tons of steel, and has difficulty selling that. Mr Walker also told British exporters to 'concentrate on four coun- tries: Brazil, Iran, Nigeria, and Venezuela' (The A of B) . Mr Walker does not, however, conclude that because in these four countries he may not have picked quite the winners he had hoped, he was absurdly arrogant to tell businessmen to concentrate on them.

When Mrs Thatcher defeated Mr Heath, Mr Walker retired to the backben- ches but not from the fray. He set up the Tory Reform Group: or rather — for he told me that Mr Michael Spicer, MP for South Worcestershire, set up the TRG he became its first patron and gave a speech at its inaugural seminar on 20 September 1975 called 'The Need for Tory Reform'. He is now president of the TRG and will be the guest speaker at its dinner this Thursday at the Conservative Confer- ence. He is often, he says, very gravely embarrassed by the awful attacks TRG members make on his Cabinet colleagues. As he points out, in a Macavity-like way: 'I have never been to an executive committee meeting of the TRG.' Nor is there a TRG parliamentary group, though an inquiry to the TRG office to see how many TRG members they would claim in the Com- mons, to compare to the 100 claimed by the Bow Group (patron: Sir Geoffrey Howe), led a TRG official to say that they were in regular communication with over 120 MPs whom they regarded as 'sym- pathetic'.

Andrew Neil, editor of the Sunday Times, is also billed to address a TRG meeting at the Conference. Mr Neil work- ed for Mr Walker in the early Seventies. He is one of a number of young assistants to Mr Walker who have subsequently done well: nowadays Mr Walker sometimes works for him, last Sunday reviewing a book about the miners' strike for the Sunday Times. Another of his assistants to have done well is the businessman Dennis Stevenson, appointed by Mr Walker in 1971 at the age of only 26 to be chairman of Peterlee New Town, and subsequently to the Advisory Committee on Pop Festivals (1972), and to a post as marketing adviser to the Minister of Agriculture (1979). Like

the Kennedys, Mr Walker is keen on youth.

In assessing Mr Walker's exact standing within the party we move into murky waters. If the waters were by sudden chance to clear, we should probably see savage fighting in progress. Supporters of Mr Norman Tebbit are convinced that Mr Walker was involved with rumours that since the Brighton bomb poor Tebbit is only half the man he used to be. There is also a story, strongly supported by people close to Number Ten, that in 1979 Mr Walker was offered the post of Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, and declined it on the grounds that he had young children. But when I asked Mr Walker whether this was true, he told me that whoever said this was 'a total liar'.

Though it is impossible to know exactly what is going on, that there is rivalry does not admit of doubt. A source close to Mr Walker has said that in the dark days of 1981 he would have tried to supplant the Prime Minister, had he been able to find 100 Tory MPs who would promise him their support. If the party should need a Wet successor to Mrs Thatcher, one who can offer some hope of winning back voters from the Alliance parties, Mr Walker intends to be the best on offer. Neither Mr Norman Tebbit nor Sir Geoffrey Howe, nor indeed Mr John Biffen, will be able to touch him for Wetness, or for plans to spend money to cut unemployment.

He went to the Ministry of Agriculture in 1979. Here his expansionist and dirigiste instincts flowered again: he urged British dairy farmers to win a larger share of the market by increasing production. The re- sulting bonanza raised his standing among shire Tories. The immense cost of the resulting surpluses lowered the standing of his hapless successor, Mr Michael Jopling, who had to introduce quotas. Intervention in defiance of the market had again proved of questionable longterm value to the people it was meant to help.

In 1983 Mrs Thatcher said to Mr Walker: `Peter, I want you to go to Energy. We are going to have a miners' strike.' However can that be known? True, the Prime Minister did not invite journalists to attend her meeting with the future Secretary of State for Energy. But the Sunday Times's book about the strike (Strike, Coronet, £2.50), introduced by Andrew Neil as 'a classic of contemporary history', records Mrs Thatcher's words for those who were not there.

Mr Walker had a good strike. While Mr Lawson was at the department, stocks had risen to a high level, though they then had to be carefully managed. Mr Scargill be- haved with consummate stupidity on a number of occasions when a better nego- tiator would have reached an exceedingly favourable settlement. Mr MacGregor annoyed Nacods, but Mr Walker helped mollify Nacods, which made Mr MacGre- gor furious that Mr Walker had acted behind his back, which made Mr Walker determined to replace Mr MacGregor at the first opportunity. This he has now done by announcing that Sir Robert Haslam will take over next year, turning Mr MacGre- gor into a lame duck. Mr Walker's policy of not invoking the Government's recently passed Employment Acts against the strik- ing miners, though it enraged many Tories, appeared to work, except to the extent that it undermined respect for the law and placed, perhaps, an even heavier burden on the police. Best of all, Mr Walker's PR skills were well to the fore. During the strike he topped and tailed in his own hand no fewer than ten letters to all Tory MPs, suggesting how they might present the dispute. Mr Jenkin did nothing comparable during his battle to abolish Mr Walker's metropolitan counties. Both fights were won, but Mr Jenkin has gone.

Since 1979 Mr Walker's standing has risen, most especially since Mr Scargill was beaten, though those close to Mrs Thatch- er tend to think that fight was won despite, not because of, Mr Walker. He has in hand the privatisation of the gas industry, with luck as big and popular a money-spinner as Telecom. He is six years younger than the Prime Minister. His ambition, which has helped him to surmount so many obstacles to advancement, is if anything stronger than ever. One Tory, borrowing Lyndon Johnson's phrase, suggested to me that Mrs Thatcher wanted Mr Walker in the Government because it was 'safer to have him inside the tent pissing out than outside pissing in'.

But if she is ever in real trouble, she is likely to find that Mr Walker has reached a place uncomfortably near the middle of the tent. Nor does anybody in the party have a finer sense of political timing than Mr Walker. He will know exactly when to make his bid for her office.

Previous page

Previous page