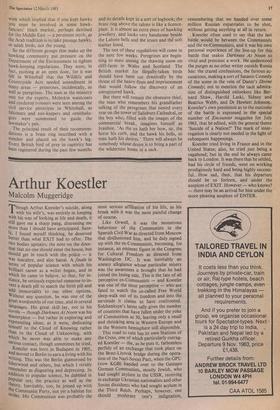

Arthur Koestler

Malcolm Muggeridge

Though Arthur Koestler's suicide, along with his wife's, was entirely in keeping with his way of looking at life and death, it still gave me a sharp pang, distressing me More than I should have anticipated. Sure- ly, I found myself thinking, he deserved better than what EXIT had to offer. The two bodies upstairs; the note on the door- Mat that no one should enter the house, but should get in touch with the police — it was macabre, and also banal. A finale in terms of popular science with which his brilliant career as a writer began, and in which he came to believe, so that, for in- stance, he seriously expected someone to in- vent a death pill to match the birth pill and add immortality to our other options. Without any question, he was one of the great wordsmiths of our time, and in several languages. His great skill lay, not in his novels — though Darkness At Noon was his masterpiece — but rather in exploring and expounding ideas; as it were, dedicating himself to the Cloud of Knowing rather than to the Cloud of Unknowing, with which he never was able to make any serious contact, though sometimes he tried. Koestler was born in Budapest in 1905, and moved to Berlin to earn a living with his writing. This was the Berlin glamorised by Isherwood and others, but which I vividly remember as disgusting and depressing. In addition to popular science, he dabbled in popular sex; the practice as well as the theory. Inevitably, too, he joined up with the Communist Party, not yet a habitat for Moles. His Communism was probably the

most serious affiliation of his life, as his break with it was the most painful change of course.

Like Orwell, it was the monstrous behaviour of the Communists in the Spanish Civil War as directed from Moscow that disillusioned him, and he duly signed up with the'ex-Communists, becoming, for instance, an eminent figure in the Congress for Cultural Freedom as directed from Washington DC. It was inevitably an uneasy allegiance whose particular misery was the awareness it brought that he had joined the losing side. This is the fate of all perceptive ex-Communists — and Koestler was one of the most perceptive — who are fated to watch the so-called Free World sleep-walk out of its freedom and into the servitude it claims to have confronted. Solzhenitsyn's latest tally gives the number of countries that have fallen under the yoke of Communism as 30, leaving only a small and shrinking area in Western Europe and in the Western hemisphere still disponible.

This road to ruin has its own Stations of the Cross, one of which particularly outrag- ed Koestler — the, as he puts it, fathomless perfidy of an exchange that took place on the Brest-Litovsk bridge during the opera- tion of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, when the GPU (now KGB) handed over to the Gestapo German Communists, mostly Jewish, who had sought asylum in the USSR, receiving in exchange Ukranian nationalists and other Soviet dissidents who had sought asylum in the Third Reich. Perhaps, however, one should moderate one's indignation, remembering that we handed over some million Russian expatriates to be shot, without getting anything at all in return.

Koestler often used to say that the last battle would be between the Communists and the ex-Communists, and it was his own personal experience of the line-up for this battle that makes Darkness At Noon so vivid and prescient a work. He understood the purges as no other writer outside Russia has: the crazed confessions, the furious ac- cusations, making a sort of Satanic Comedy of the scene in the vein of Dante's Divine Comedy; not to mention the tacit admira- tion of distinguished onlookers like Ber- nard Shaw, Harold Laski, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, and Dr Hewlett Johnson. Koestler's own pessimism as to the outcome of the battle is expressed in the special number of Encounter magazine for July 1963, that he edited, with the general theme `Suicide of a Nation?' The mark of inter- rogation is clearly not needed in the light of subsequent happenings.

Koestler tried Eying in France and in the United States; also, he tried just being a vagabond; but in the end he always came back to London. It was there that he settled, had his circle of friends, went on working prodigiously hard and being highly success- ful. How sad, then, that his departure should be so forlorn, and under the auspices of EXIT. However — who knows? — there may be an arrival for him under the more pleasing auspices of ENTER.

Previous page

Previous page