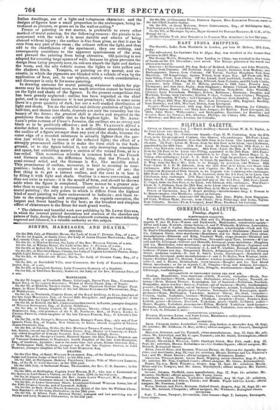

FINE ARTS.

THE NEW PALACE AT WESTMINSTER.

THE " Palace at Westminster," as the new Houses of Parliament are officially called, is rapidly rising on the river-side. The magnitude of the massy pile, the richness of its architectural adornments, and their beauty of execution are conspicuous ; though the effect of the building as a whole cannot be fully appreciated before the two great towers— the Victoria, or Record Tower, and the Speaker's, or Clock Tower— are erected. The river-front may, however, be viewed by itself so soon as the façade is completed by putting on the roof and the pin- nacles of the turrets : but until then, it is unfair and scarcely possible to form a judgment even of this portion of the design ; for the appearance of the elevation will depend very greatly on the " sky-outline. Both description and criticism at the present moment, therefore, would be premature. We may remark, however, that, so far as the building has advanced, it differs materially from the original design : turrets have been substituted for buttresses ; niches with statues in them have been added ; the tracery and other enrichments are more superb ; and the introduction of the armorial bearings of all the Sovereigns of England, in high relief, is a felicitous afterthought, that adds greatly to the mag- nificence of the sculptured decorations. Besides these and other altera- tions and additions, the roof, we understand, will form a prominent feature of the structure ; whereas in the published views it is not vi- sible. These changes, so far as they have proceeded, are decided im- provements; and in making them, Mr. BARRY has given fresh proofs of his taste and judgment, by availing himself of the interval to re- vise his original sketch and fill up the details of its outline, as a skilful painter modifies and elaborates his design in executing the finished pic- ture. We have noticed in the progress of the building, that the most minute points of exterior decoration have been tested by experimental models set up to show the effect of the intended improvements. In all that relates to the architectural arrangements both of the exte- rior and interior of the edifice, the architect of course exercises entire control ; in the selection of artists and designs for the interior decora- tions and furniture, be will also have an influential voice. So far as re- gards the ornamental details, in which embellishment is subordinate to architectural display, and where the designer has examples to guide his invention—as for instance, in the heraldic blazonries, the painted friezes and borders, the wood-carvings, metal-work, stained glass, and pave- ments—there will be very little difficulty : authorities and precedents can be referred to by the competitors, who have only to give to their ideas shape and impress in accordance with the style of the Tudor pe- riod. But with the painters and sculptors the case is different : it is not for them to gothicize their art so that the marble and fresco should appear to be the work of the fifteenth century ; yet both should har- monize with the general character of the building, and appear to form a component part of it. It is not enough to cover the walls with pic- tures and stick up rows of statues, as in a museum : every piece of paint- ing and sculpture should seem essential to the place it fills, and insepar- able from it : however beautiful in itself, each should be in effect a part and parcel of a grand whole. This is the leading principle of monu- mental design ; in which the sister arts of architecture, sculpture, and painting, unite their perfections to captivate the sense and excite the imagination ; vying with one another, not as rivals but as friends. The architect is one, the sculptors and painters are many ; and how shall a number of artists, each of different views, powers, and style, and all working independently, combine to produce this harmonious result? Such an inquiry is naturally suggested ; and we answer thus— by observing the laws that govern monumental art. What are these laws? This is a question that we think the Royal Commission should take upon themselves to answer. We had hoped that Mr. HAYDON would have thrown some light upon it in his Lecture on the Cartoons this week but he was too full of himself to find much room for his sub-

ject. It is a question that presses for an answer, though it has scarcely been raised publicly ; and in default of souse more learned exponent, we will venture on a few remarks that occur to us at the moment— wishing to moot the point, but not pretending to settle what has yet to be discussed.

A perfect work of monumental art should express one grand and complete idea; every portion contributing in its due measure to evolve the entire conception. Such were the temples of Egypt and Greece ; such are the Alhambra, St. Peter's, and the Vatican, and many other of the churches and palaces of Italy. Most ecclesiastical structures, espe- cially the Gothic cathedrals of this and other countries, were designed in this spirit : but interruptions in the works and iconoclastic fanaticism have mutilated many noble examples ; and the barbarism of chapters and churchwardens has defaced what time and Puritanical zeal had left. The characteristics of the Palace of the Legislature at Westminster, so far as we are enabled to form a judgment of them, are massive gran- deur and symmetrical regularity combined with elegant proportions and sumptuous embellishment ; solidity and compactness distinguishing the design as a mass, and regal profusion of decoration the several parts. The breadth and repose that we anticipate will be predominant in the effect of the whole stricture seen from without—the rich details being subordinate in a general view, though inviting attention from a nearer point—should also pervade it within. Next to handsome proportions, light and space are the chief elements of beauty in an interior. These are materially influenced by the character of the decorations ; which may either darken and contract, or enliven and expand the room. Strong shadows cast by high projections or deep recesses, heavy ornaments, and large spaces covered with intense hues, tend to bring the walls nearer to the eye and to diminish the reflecting surfaces, thus at awe darkening the apartment and contracting its apparent area ; whereas ornaments small in proportion to the walls, the absence of projections and recesses, and a sparing use of deep colours, produce a lively and cheerful effect, quite compatible with splendour and richness. Magni- ficence in this country is so constantly associated with sombre heavi- ness, that grandeur and gloom are almost as much identified as dulness and decorum. Bright colours in decoration are as yet new to the pra.--. sent generation, and they startle unaccustomed eyes : the gayety of the:. Temple Church shocks many visiters, habituated to Puritanical privation of lively hues, and the pauper glare of churchwardeu's whitewash ; but the church-builders of the olden time feasted their eyes on the rich harmonies of colour and blazonry as we do our ears on the harmonies of the choir and organ. Painting is as essential as sculpture to the completeness of the Gothic style of architecture : pictures on the walls, stained glass in the windows, and heraldic and other devices in gold and colour on the ceilings, are as much ingredients of it as crockets,. bosses, corbels, mouldings, and string-courses; and every niche should contain its statue.

In the new Palace, as is every well-designed edifice in this style, there will be places provided both for statues aid pictures : it would no more be complete without them than the pediment of a classic por- tico wanting its sculpture, or the dome of a modern building destitute of paintings. To fill these places with propriety and due effect, the works of the painters and sculptors most be designed in a style suitable to the purpose,—namely, the architectonic : this, as the term imports,.. implies a character of design in which the figures are, as it were, built up with the edifice. Neither quaintness nor rigidity are requisite in the statues; only a severe simplicity and dignified quietude, impressing by the gravity and solemnity of aspect, but not attracting by any display of attitude or costume. These qualities admit of the highest degree of refinement in the art, and are in no way inconsistent with grace and elegance ; so far from it, the perfect repose of the form is equally favour able to beauty and grandeur of contour: violent or suspended action would be utterly inadmissible. The works of Fle.,xn.ax are models of this style. The architectonic style of design, as applied to mural painting, is so nobly exemplified in the paintings by RAFFAELLE that adorn the cham- bers of the Vatican, and in his cartoons at Hampton Court, that the study of these immortal works, with reference to their composition and arrangement chiefly—for which the numerous prints furnish facilities— is the best guide the artist can possibly have. In these designs the utmost amount of beauty and variety is blended with majestic simplicity and uniformity. The balance of parts in the distribution of the groups is perfect ; the corresponding masses are not so similar as to make this apparent at first, but the general symmetry of disposition is satisfying to the eye of the casual observer, and attracts the admiration of the attentive student. Architectural forms enter largely into the composi- tion of these designs, and are so prominent in every one where their introduction is admissible, that it is impossible to avoid the inference that this was a recognized element of mural painting. The "Last Supper" of LEONARDO DA VINCI is an equally strong case in point. Not only in the "School of Athens " and the " Incendio del Borgo," but in the " Dispute of the Sacrament," where there is no room for the introduction of architecture, the leading lines of the compo-

sition are architectonic. Another characteristic of the Vatican frescoes is the quantity of space thrown into each ; not waste canvass to let, but room so artfully filled that the very forms themselves have the effect of making it seem more extensive, by opening vistas of columns and arches. Light too is freely admitted by the same means ; and both in the out-door and in-door scenes a sense of openness and atmo- sphere is communicated. So also in the " Last Supper." These mural pictures, as it were, open the walls ; letting in a flood, of light and beauty ; while the arrangement of the composition renders them a part of the architecture of the building. The cartoons of RAFFAELLE, which were designed for tapestry-hangings, have less ample space; the figures are nearer the eye, and the composition is more crowded: but architectural forms are introduced wherever admissible ; the leading lines are geometrical, and the masses are well balanced. They are only less architectonic, wanting the quantity of space, atmosphere, and light, given in the mural paintings. We need not here speak of the decorations of the Loggie of the Vatican, for the designs of Rarrer.u.s fill the spandrils of the arches : nor is it necessary to allude to the Pro-

phets and Sybils of MICHAEL ANGELO in the Sistine Chapel, for they adorn the covings and spandrils of the roof; and morever they partake of the nature of sculptural design, being single figures or groups. The frescoes of the Farnesina Palace, the Villa Madams, and other Italian dwellings, are of a light and voluptuous character ; and the designs of figures bear a small proportion to the arabesques. being in- troduced as pictures, or gems set in the wall or ceiling.*

Fresco or painting on wet mortar, is preferable to every other method of mural painting, for the following reasons: the picture is in- corporated with the wall; it is most durable and admits of being cleaned without injury ; the surface is free from gloss, so that it can be seen from any part of the room; colours reflect the light, and thus add to the cheerfulness of the apartment ; they are retiring, and consequently contribute to the apparent spaciousness of the area, and prevent the painting from being obtrusive. Oil-painting is not adapted for covering large spaces of wall; because its gloss prevents the design from Wing properly seen, its colours absorb the light and darken the room, and the oily vehicle causes the lights to turn yellow and the shadows black. Tempera, or painting on dry mortar, and en- caustic, in which the pigments are blended with a vehicle of wax by the application of heat, are, in our opinion, scarely worth consideration ; and distemper is only fit for scene-painting.

In drawing cartoons for mural painting, whatever vehicle for pig- ments may be determined upon, too much attention cannot be bestowed on the light and shade of the figures. In the present competition this hats been greatly neglected : outline has been regarded as the chief point, and in many instances it is too prominent ; while in some cases there is a great quantity of dark, but not a well-studied distribution of light and shade. Yet on the careful and delicate gradation of light into half-tint, and thence into shade, depends not only the rotundity but the beauty of the forms: the greatest skill is shown and required in the gradations from the middle tint to the highest light. In Mr. ARMI- TAGE'S prize cartoon of Ccesar's Invasion, the outlines are so strong and black as to be positively offensive ; and in Mr. CLAXTON'S Alfred a similar defect is conspicuous. It is a self-evident absurdity to make the outline of a figure stronger than any part of the shade, because the outer edge of a rounded substance is actually lighter than the por- tion just within it, by reason of the reflected light ; the effect of a strongly pronounced outline is to make the form stick to the back- ground, or to the figure behind it, not only destroying atmosphere and space, but exhibiting merely a section of the rotund form, as in a bas-relief. This monstrous mistake is common both in the French and German schools; the difference being, that the French is a semi-rotund relief, and the German is flat, like medallic relief. This prominence of outline, moreover, is fatal to massing in com- position; indeed, it is opposed to all true principles of art: the first thing is to get a correct outline, and the next is to lose it by filling it with light and shade. Outline is a mere convention, and does not exist in nature: it is the mould of form, and should be thrown aside when the figure is completed. There cannot be a greater mis- take than to suppose that a pronounced outline is a characteristic of mural painting : the only points in which it differs from the highest kind of easel painting we have endeavoured to indicate ; and these re- late to the composition and arrangement. As regards execution, the largest and freest handling is the best; as the broadest and simplest effect of chiaroscuro is the fittest for such grand works.

* The elaborate and beautiful work now publishing by Mr. LEWIS GRoNER, in which the internal painted decorations and stuccoes of the churches and palaces of Italy, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, are most delicately engraved and coloured, is a valuable authority on this subject.

Previous page

Previous page