The Unknown Borders

By WILLIAM DEAN

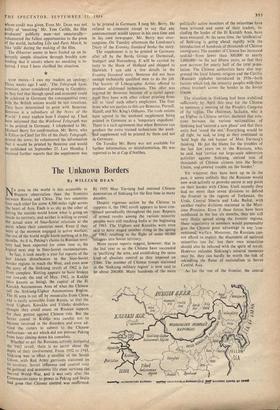

No area in the world is less accessible to Western observation than the frontiers between Russia and China. The two countries face each other for some 4,500 miles right across the heart of Asia. Each is as shy as the other of letting the outside world know what is going on inside its territory, and neither is willing to reveal the actual state of Sino-Soviet relations at the Point where their countries meet. Even if they were at the moment engaged in active warfare, the rest of the world might know nothing of it for months. As it is, Peking's claims to Russian terri- tory had been expected for some time as, the logical next step in Sino-Soviet recriminations.

In fact, it took nearly a year for reports of the last known disturbances in the Sino-Soviet border regions to reach the West, and even now the story of the Sinkiang revolt of 1962 is far from complete. Rioting appears to have broken out towards the end of May, 1962, in Kuldja (also known as Ining), the capital of the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Area of what the Chinese Call the Sinkiang-Uighur Autonomous Region. The Ili area is cut off by mountains from China and is easily accessible from Russia, so that the local Uighurs, Kazakhs and Uzbeks doubtless thought they could count on Russian support for their protest against Chinese rule. But the Soviet consul in Kuldja was careful not to become involved in the disorders and even ad- vised the rioters to submit to the Chinese authorities—an act which did not prevent Peking from later closing down his consulate.

Whether or not the Russians actively instigated the 1962 revolt, there is no Secret about the depth of their involvement. From 1932 to 1943, Sinkiang was in effect a satellite of the Soviet Union, with Red Army garrisons stationed on its territory. Soviet influence and control over its political and economic life even survived the Second World War, and it was only after the C-ommunists came to power in Peking and Stalin had gone that Chinese control was reaffirmed.

By 1955 Mao Tse-tung had restored Chinese domination of Sinkiang for the first time in many decades.

Despite vigorous action by the Chinese to suppress it, the 1962 revolt appears to have con- -4,inued sporadically throughout the year. Reports of armed revolts among the various minority peoples were still reaching India at the beginning of 1963. The Uighurs and Kazakhs were even said to have staged another rising in the spring of 1963, resulting in the flight of some 60,000 'refugees into Soviet territory.

More recent reports suggest, however, that in the last year or so the Chinese have succeeded in 'pacifying' the area, and establishing the same kind of absolute control as they imposed on Tibet. The number of Chinese troops stationed in the 'Sinkiang military region' is now said to be about 200,000. Many hundreds of the more

politically active members of the minorities have been arrested and some of their leaders, in- cluding the leader of the Ili Kazakh Area, have been executed. At the same time, the `sinification' of Sinkiang is going ahead rapidly with the introduction of hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants. The number of Chinese has increased tenfold—from fewer than 300,000 to nearly 3,000,000—in the last fifteen years, so that they now account for nearly half of the total popu- lation. The Chinese authorities have also sup- pressed the local Islamic religion and the Cyrillic (Russian) alphabet introduced in 1956—both factors which link the minority peoples with their ethnic brothers across the border in the Soviet Union.

The situation in Sinkiang had been stabilised sufficiently by April this year for the Chinese to summon a meeting of the People's Congress of the region. The chairman, Saifudin, who is an Uighur in Chinese service, declared that rela- tions between the various nationalities of Sinkiang had 'entered a new phase' and that their unity had 'stood the test.' Everything would be all right, he said, so long as they continued to 'hold high the red banner of Mao Tse-tung's thinking.' He put the blame for the troubles of the last few years on to the Russians, who, he said, had 'carried out large-scale subversive activities against Sinkiang, enticed tens of thousands of Chinese citizens into the Soviet Union, and created trouble on the border.'

Yet whatever they have been up to in the past, it seems unlikely that the Russians would now wish actively to provoke unrest at any point on their border with China. Until recently they had no more than seven divisions to defend the frontier in the regions of Turkestan, the Urals, Central Siberia and Lake Baikal, with another twelve divisions stationed in the Mari- time Province. Even if these forces have been reinforced in the last six months, they are still very thinly spread along the frontier regions. Sheer superiority in numbers would presumably give the Chinese great advantage in any 'con- ventional' warfare. Moreover, the Russians can- not afford to exploit the discontent of national minorities too far, lest their own minorities should also be infected with the spirit of revolt. However valuable Sinkiang's mineral resources may be, they can hardly be worth the risk of rekindling the flame of nationalism in Soviet Central Asia.

As for the rest of the frontier, the central

Part, bordering on Outer Mongolia (the 'Mongo- lian People's Republic), is quiet, since the Mongols have remained loyal to Moscow, and the Chinese appear to have been ousted. But the defence of Mongolia presumably rests in Russian hands and must be a considerable bur- den. On the other side of the frontier, in Inner Mongolia, population transfers have reduced the Proportion of Mongols from one-third in 1952 to leis than one-tenth today. Chinese rule is resented and there were serious disturbances in 1961 and 1962.

It is in the Far East alone that there have been no reports of serious incidents. The Russians were well and truly ousted from Man- churia ten years ago. Their presence on the Pacific- coast reflects anxiety about American in- tentions rather than concern about possible Chinese encroachments. But the balance may now have changed.

As for the validity of the present Sino-Soviet frontier as a whole, the Russian view is quite clear. They claim that it was 'formed historically' and that the only aspects open to discussion are matters of detail and more precise delineation. The Chinese position is more obscure. In 1960 Chou En-lai was quoted as saying: 'There is ?WY a very small discrepancy on maps and it IS very easy to settle.' On the other hand, the Chinese have reserved to themselves the right to `renegotiate' the 'unequal' treaties by which China lost territory to various European nations and Japan. In a map published in 1954 the Chinese Communists laid claim to large areas of what is now Soviet territory, including a large part of Soviet Central Asia, with Tashkent, Alma-ata and Frunze, the whole of the Ili valley, the Amur river basin, the maritime provinces of Eastern Siberia, including Vladi- vostok, and the island of Sakhalin.

When, in the course of Sino-Soviet polemic, Khrushchev taunted the Chinese with their tolera- tion of Hong Kong and Macao, the Chinese replied: 'In raising questions like this, do you intend to raise all the questions of unequal treaties and have a general settlement? Has it ever entered your heads what the consequences would be? Can you seriously believe that this will do you any good?' The Russians appear to have taken this hint and have since refrained from raising the question of their frontier with their former allies.

It appears, then, that something like an armed truce had been established along the whole length of the frontier. Yet China's transformation from a friend and ally into a rival is now imposing great strain on the Russian leaders. Fear of the hordes of yellow-skinned men in the East is deeply ingrained in the Russian character, and Marxism has done nothing to eradicate it. Khrushchev has inherited all the imperial re- sponsibilities of the Tsars and they seem likely to cause him, or his successor, quite as much trouble.

Previous page

Previous page