Exhibitions 1

Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective (The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, till 7 January 1998)

Dada for the masses

Roger Kimball

Seeing the huge new retrospective of works by Robert Rauschenberg involves a mini tour of Manhattan. One starts at the Guggenheim Museum at Fifth Avenue and 89th Street, where hundreds of objects made or at least signed by Rauschenberg are arranged in roughly chronological order, from the beginning of Rauschen- berg's career up to about 15 minutes ago.

One then treks downtown to the Guggenheim's SoHo outpost at Broadway and Prince Street, where Rauschenberg's technology-based and multi-media works are on view, along with more paintings, sculptures, collages, and 'combines' from the last year or so. Then one travels across town to Spring and Hudson Streets, where the Guggenheim Museum at Ace Gallery is showing 'The 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece', a work-in-progress that began in 1981 and currently consists of 189 parts and takes up some 1,000 feet of wall and floor space.

After making these rounds, a friend and I wearily decanted ourselves into a taxi and headed back uptown. We were stopped at a traffic light when a car pulled up beside us and an Airedale in the backseat began barking furiously through a half-opened window. When I turned to look at the dog, he suddenly stopped barking, yawned broadly, and lay down. 'He doesn't know whether to bark or yawn,' my friend observed. Which more or less sums up my reaction to this biggest-ever travelling road show of works by Robert Rauschenberg.

There are worse things celebrated as great art today: things, anyway, that are more aggressively repellent. But I cannot remember an exhibition that left such a melancholy aftertaste. A press release claims that, in his nearly 50-year career, 'Robert Rauschenberg has redefined the art of our time.' There is, alas, a sense in which this is true. Not that there is any- thing original or innovative about Rauschenberg's art. On the contrary, his work is primarily a highly commercial ver- sion of what Marcel Duchamp was doing in the teens and twenties with his 'ready- mades'. In essence, it is a window-dresser's version of Dada: Dada (slightly) prettified and turned into a formula — Dada, in short, for the masses.

Like Andy Warhol, Rauschenberg's chief genius has been for celebrity. His works are props in a gigantic publicity campaign whose purpose is to foster a species of brand-name recognition. In Rauschen- berg's case, the brand in question is gener- ic: it's art in general. What we are meant to admire is not the aesthetic achievement of Rauschenberg's work — that, indeed, is a question that scarcely arises — but rather the fact that it somehow managed to achieve the status of art in the first place. Like Dr Johnson's dog prancing on its hind legs, it's not how well it performs but the fact that it performs that way at all that inspires wonder.

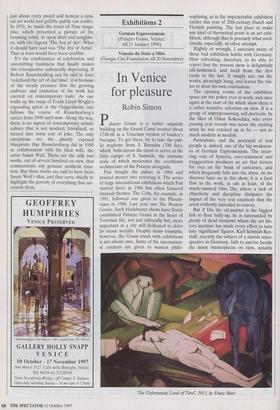

Writing in 1967, the American critic 'Monogram' (Angora goat and rubber tyre), 1955-59, by Robert Rauschenberg Clement Greenberg noted that many con- temporary artists were exploiting 'the shrinking of the area in which things can now safely be non-art'. Rauschenberg, whom Greenberg described as a 'proto- Pop' artist, has again and again proved himself extraordinarily adroit at this game, ready at a moment's notice with an old bathtub, a crumpled cardboard box, a wooden frame filled with dirt and mould, or simply a blank canvas to offer an eager art market. All of which is to say that by the time Rauschenberg came on the scene the area that could 'safely be non-art' had already been collapsed nearly to zero. Rauschenberg's talent — again like Warhol's (and like that of his early collabo- rator Jasper Johns) — was to look back on this collapse with a knowing, eminently packageable smirk.

Much of the smirk, especially in Rauschenberg's early work, was directed at the art of his older contemporaries. This is part of what made Rauschenberg such a hit among intellectuals, for whom the specta- cle of artistic self-reference is irresistible. It reminds them, just barely, of having discov- ered something. Rauschenberg offers them a battered wooden box into which he has hammered a bunch of rusty nails and tossed a few pebbles: they think 'Joseph Cornell, sort of', and are happy.

You can tell a lot about Rauschenberg's work simply from its list of ingredients. Consider 'Monogram' (1955-59), which the Moderna Museet in Stockholm actually paid good money to acquire. This typical 'combine' consists of oil paint, paper, fab- ric, printed paper, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe heel, and tennis ballon canvas, with oil paint on an Angora goat (stuffed) wearing an automobile tyre and standing on a wooden platform mount- ed on four casters. It's almost enough to make one sympathise with the animal- rights fruitcakes. (It certainly makes one sympathise with the museum conservators charged with 'preserving' this stuff.) There's a character in Dickens's Our Mutual Friend known as 'the golden dust- man'. Rauschenberg is a kind of golden dustman. At least, an exhibition of his work reminds one of nothing so much as a visit to a gigantic dustbin or junk yard, and one that magically coins vast sums of money. It will be objected that there is nothing unusual about this: that many, maybe most, of the more glamorous precincts of the contemporary art world are every bit as trashy as those inhabited by Robert Rauschenberg. I readily concede the point. But there is something special about Rauschenberg. It has partly to do with longevity — Rauschenberg has been around a long time now — partly with his facileness. What Rauschenberg produces is undoubtedly junk, but he has managed to produce a mighty impressive mound of it and he has done so with buoyant insou- ciance.

Over the years, Rauschenberg has won just about every award and honour a cyni- cal art world and gullible public can confer. In 1976, he made the cover of Time maga- zine, which presented a picture of the beaming artist, in open shirt and sunglass- es, with the legend 'The Joy of Art'. What it should have said was 'The Joy of Artist'. That at least would have been credible.

It's the combination of celebration and unremitting trashiness that finally makes this retrospective unbearably depressing. If Robert Rauschenberg can be said to have 'redefined the art of our time', it is because of the steady pressure that the growing embrace and exaltation of his work has exerted on contemporary taste. As one walks up the ramp of Frank Lloyd Wright's expanding spiral at the Guggenheim, one follows the course of Rauschenberg's career from 1949 until now. Along the way, there is no aspect of contemporary artistic culture that is not mocked, trivialised, or turned into some sort of joke. The only exceptions are the ghostly exposed blueprints that Rauschenberg did in 1950 in collaboration with his then wife, the artist Susan Weil. These are the only two works, out of several hundred on view, that communicate any genuine aesthetic emo- tion. But these works are said to have been Susan Well's idea, and they serve chiefly to highlight the poverty of everything that sur- rounds them.

Previous page

Previous page