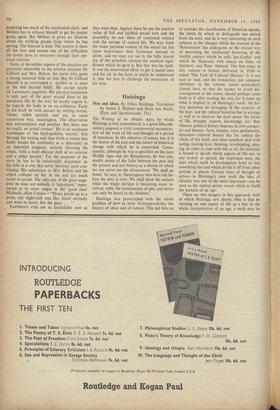

Huizinga

Men and Ideas. By Johan Huizinga. Translated by James S. Holmes and Hans van Marie. (Eyre and Spottiswoode, 25s.)

The Waning of the Middle Ages, by which Huizinga is best remembered, is a great fifteenth- century pageant, a vivid, controversial reconstruc- tion of the ways of life and thought of a period of transition. In this selection of essays, too, it is the drama of the past and the nature of historical change with which he is concerned. Conse- quently, although he was a specialist on the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance, he was con- stantly aware of the links between the past and the present and saw history as a drama of which we can never see the denouement. 'We shall go home,' he says, as 'theatregoers who have left be- fore the play is over. We shall draw the curtain while the tragic intrigue is becoming more in- volved, while the lamentations of pity and terror can only be heard in the distance.'

Huizinga was preoccupied with the whole problem of how to write Geistesgeschichte, the history of ideas and of culture. This led him on

to consider the classification of historical epochs, the labels by which to distinguish one period from the next; and he is very interesting on such subjects as the changes which the concept of the 'Renaissance' has undergone, or the correct way of describing the intellectual flowering of the twelfth century which he calls 'pre-Gothic' and which he illustrates with essays on John of Salisbury and Peter Abelard. The first essay in this volume—a lecture delivered in 1926—is called 'The Task of Cultural History.' it is not easy to read, and the translation, just adequate elsewhere in the volume, seems particularly clumsy here, so that the reader, to avoid dis- couragement at the outset, should perhaps come back to it after reading the rest, for it sums up what is implicit in all Huizinga's work. All his- tory presumes an arranging of the material of the past; and the cultural historian has to arrange as well as to discover the facts about 'the forms of life, thought, custom, knowledge, art.' But, whereas political history imposes its own categor- ies and themes—laws, treaties, wars, parliaments, dynasties—cultural history has for subject the whole of life itself, and must somehow deal with eating, making love, thinking, worshipping, play- ing. In order to cope with this at all, the historian is bound to decide which aspects of life are, in any society or period, the important ones, the ones which mark its development from or into something else and which divide it off from other periods or places. Certain ways of thought or action—in Huizinga's own work the idea of chivalry was one of the most important—can be used as the central points round which to build the portrait of an age.

There are two dangers in this approach, both of which Huizinga saw clearly. One is that by insisting on one aspect of life as a key to the whole interpretation of an age, a myth may be built up which is remote from the truth. To this he could only reply that it is the task of historical scholarship of an exact kind to stop the historian from stepping over from, as he put it, 'mor- phology into mythology,' and that it is only by limiting strictly the questions he is asking that the historian can hope to avoid talking nonsense. The other danger is that, in writing of society as a whole, the individual is lost. Huizinga writes of the fifteenth' century in France without men- tioning Joan of Arc (he apologises for it himself in a brilliant essay, reprinted in the present volume, on Shaw's Saint Joan), and of Abelard with only a cursory reference to Hdloise. Yet his major works and the arguments and examples in these essays show that these dangers can be avoided. The importance of Huizinga is to have demonstrated that a history book of which the central character is Jan van Eyck can be as valid as one which centres on Joan of Arc.

JAMES JOLL

Previous page

Previous page