ONLY THE BUTLER REMAINS

Martin Vander Weyer recounts a cautionary

tale of capitalism, or how Sotogrande-on-Tees and Samsung replaced the Londonderrys

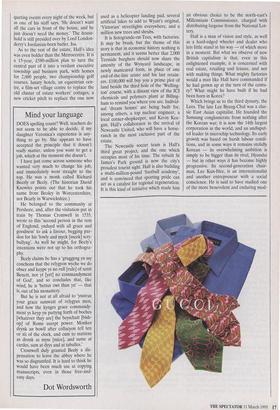

SINCE CAPITALISM has not yet passed into legend, no one has yet created a theme park to celebrate it. But Wynyard in Cleveland, site of the new Samsung elec- tronics factory, is the next best thing, or even better: a living demonstration of the free play of economic forces on landscape, demography and family fortunes.

Wynyard is both a news story and a his- tory lesson. It tells of one long dynasty and two short ones: respectively, the Tempests of Old Durham, the Halls of Ashington and the Lees of South Korea. Unlike a real theme park, however, it does not readily distinguish between the princes and the pirates. In the history of capitalism, one man's hero is inevitably another man's villain.

The Tempests were ancient grandees: one of them fought with Henry V at Agin- court. Their lands were rich in coal deposits; in the late 18th century they began to develop the south Durham coal- field and acquired the Wynyard estate, between Billingham and Sedgefield. This inheritance passed to Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane Tempest, who married in 1819 Lord Stewart of Mount Stewart, later 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, a short, bad- tempered man who was half-brother to the foreign secretary Castlereagh and a friend of the Duke of Wellington.

The couple commissioned Philip Wyatt (a forebear of Woodrow, the News of the World's Voice of Reason) to build them a Grecian mansion at Wynyard, based on designs for Wellington's unbuilt Waterloo Palace. Before it was completed, it burned down and had to be started again, but it became one of the smartest venues of 19th-century social life, frequented by Dis- raeli (who 'never left London ... with such anticipation of happiness') and visited by everyone who was anyone, from Dick- ens to Bismarck. Even the Privy Council met there once, the Clerk noting that the place was 'gloomy with Middlesbrough smoke'.

The Londonderrys, meanwhile, did not neglect their coal-owning responsibilities. In 1844, they tried to starve striking miners by threatening shopkeepers who supplied them, and the Marchioness was noted for her 'annual speeches of advice and encouragement' to her workforce. In the 1890s, the 6th Marquess broke another strike by shipping in workers from his Mount Stewart estates in Ulster.

As dynasties become grander, so they become more eccentric, and softer at the edges. The 6th Marquess's wife, a mistress of the Prince of Wales, was believed to have left her bedroom window open at night to allow access for a gamekeeper called Houliston. The Shah of Persia was so smitten (and so hazy about English social custom) that he offered to buy her. Her successor, known to friends as 'Circe the Sorceress', was the great political host- ess of the Twenties and Thirties, enter- taining 2,000 guests at Londonderry House in Park Lane on the eve of the Opening of Parliament and conducting an intense platonic relationship with Ramsay Macdonald. Circe's husband, however, earned the nation's scorn by calling for rapprochement with Hitler and paying the Nazi leader a visit shortly before Munich.

After the war, the rot set in. Unmanage- able as a private house, Wynyard became a teachers' training college. The 8th Mar- quess, who had actually worked in a mine for a year, was one of the few coal-owners to speak in favour of nationalisation. His son Alastair, the present holder of the title, usually described as a musician, took the house back in the early 1960s and made it habitable, but could never afford to maintain it. After his first divorce in 1971 (his wife ran off with the pop singer Georgie Fame, the court later accepting that Londonderry was not the father of her infant son) he started selling land. In the early Eighties, he sold the family silver. Finally, in 1987, describing himself as 'bro- ken-hearted', he sold Wynyard with its remaining 5,300 acres for £3 million to John Hall. He never came back.

So much for old British capitalism. The Londonderrys took wealth out of the ground and spent it magnificently, but they failed to invest it in anything which might eventually keep them in their accustomed style, or to produce heirs capable of creat- ing it in new ways. Their last legacy to Teesside is a stretch of wooded, secretive, orderly countryside astride the A689, unmistakably the domain (although the house itself is out of sight) of a man of some importance. And so it is: Sir John Hall is a more potent figure in the north- east today even than the 3rd Marquess was 150 years ago. He is the personification of new British enterprise, and his bulldozers are at work on Wynyard.

Born at North Seaton Colliery in Northumberland, Hall is the son and grandson of miners, and began his own career as a mining surveyor. Later he became an estate agent and a developer of small industrial units in the Newcastle area. Then in 1979, after a trip to see the shop- ping malls of America, he had an extraordi- narily bold, quintessentially Thatcherite idea: he decided to build the Metrocentre, Europe's biggest shopping complex, on an old slag-tip beside the Tyne at Gateshead, sandwiched between a coal-yard and a brewery.

A man of prodigious energy, Hall is a fearsome persuader and political operator (who has described the late T. Dan Smith, Newcastle's once-jailed council boss, as 'a visionary before his time') but also, in his own words, 'a capitalist with a conscience'. Even Hall's own son, Douglas, who has fol- lowed him into the property business, is supposed to have told his father that the Metrocentre was 'a f***ing stupid idea'. But Hall persuaded Gateshead to change its structure plan (the planning authorities' bible), which had not allowed for retail development; he persuaded Marks & Spencer to come in as the anchor tenant; and he persuaded Kenneth Baker, as envi- ronment minister, to change the route of the adjacent Al. Having completed the development, he sold it (in another curious twist of capitalism's thread) to the Church Commissioners, at an undisclosed but evi- dently enormous profit.

Part of that profit bought Wynyard, and £4 million more restored the mansion to its original glory. At first Hall was going to turn it into a conference centre, then he installed the headquarters of his company, Cameron Hall, there; but now he just lives in it, or at least in its east wing, using the 120-foot-long sculpture gallery and the 32- seat dining-room only on special occasions. He could hire out the state-rooms for ban- queting events every night of the week, but as one of his staff says, 'He doesn't want all the cars in front of the house, and he just doesn't need the money.' The house- hold is still presided over by Lord London- derry's Jordanian-born butler, Isa.

As to the rest of the estate, Hall's idea was even bolder than the Metrocentre. It is a 15-year, £580-million plan to turn the central part of it into a verdant executive township and business park, with homes for 2,000 people, two championship golf courses, luxury hotels, an equestrian cen- tre, a film-set village centre to replace the old cluster of estate workers' cottages, a new cricket pitch to replace the one now used as a helicopter landing pad, several artificial lakes to add to Wyatt's original, `Victorian' streetlights everywhere, and a million new trees and shrubs.

It is Sotogrande-on-Tees, with factories. It may be brash, but the theme of this story is that in economic history nothing is permanent, and it seems better that 2,000 Teesside burghers should now share the amenity of the Wynyard landscape, in newly manicured form, in place of one end-of-the-line aristo and his last retain- ers. £100,000 will buy you a prime plot of land beside the third hole of the 'Welling- ton' course, with a distant view of the ICI chemicals and polymers plant at Billing- ham to remind you where you are. Individ- ual 'dream homes' are being built for, among others, a top nuclear engineer, a local corner-shopkeeper, and Kevin Kee- gan, Hall's collaborator in the revival of Newcastle United, who will have a horse- ranch in the most exclusive part of the estate.

The Newcastle soccer team is Hall's third great project, and the one which occupies most of his time. The rebuilt St James's Park ground is now the city's proudest tourist sight. Hall is also building a multi-million-pound 'football academy', and is convinced that sporting pride can act as a catalyst for regional regeneration. It is this kind of initiative which made him an obvious choice to be the north-east's Millennium Commissioner, charged with distributing largesse from the National Lot- tery.

Hall is a man of vision and style, as well as a hard-edged wheeler and dealer who lets little stand in his way — of which more in a moment. But what we observe of new British capitalism is that, even in this enlightened example, it is concerned with real estate, retailing and leisure, and not with making things. What mighty factories would a man like Hall have commanded if he had grown up at the turn of the centu- ry? What might he have built if he had been born in Korea?

Which brings us to the third dynasty, the Lees. The late Lee Byung-Chul was a clas- sic East Asian capitalist. He founded the Samsung conglomerate from nothing after the Korean war; it is now the 14th largest corporation in the world, and an undisput- ed leader in microchip technology. Its early growth was based on harsh labour condi- tions, and in some ways it remains stolidly Korean — its overwhelming ambition is simply to be bigger than its rival, Hyundai — but in other ways it has become highly progressive. Its second-generation chair- man, Lee Kun-Hee, is an internationalist and another entrepreneur with a social conscience. He is said to have studied one of the more benevolent and enduring mod- els of old British capitalism, the Cadbury's community at Boumeville, and he has recently encouraged his staff to go home earlier and take up hobbies. (He is also, animal welfarists will be glad to know, unusually fond of dogs — as pets, rather than as the pita du jour for which Seoul used to be famous.) But one of the problems of progressive- ness, in the Asian context, is rising staff costs: Korean wage inflation is in double digits. And, surprising though it may seem, some British assembly workers are paid at a substantially lower rate than their Kore- an counterparts — £2.70 per hour, to be precise, at Samsung's factory at Billing- ham.

Hence, at five to five on a Friday evening some months ago, a team from Samsung arrived to look at the Wynyard site, and our three dynasties metaphorical- ly collided. (Even the long-dead London- derrys contributed to the deal: by deciding not to mine under Wynyard itself, they left the land less contaminated than the old industrial sites which were competing for Samsung's attention.) The result will be a £600-million, 3,000-employee complex, the largest foreign investment in Britain for a decade, of which the first part will rise from a sea of mud to become operational by August. With Samsung in place, Hall's shrewd £3-million purchase was estimated to be worth £76.5 million.

Given that there are over 60,000 unem- ployed in Cleveland and Durham, it is per- haps not surprising that environmental opposition to Samsung, even from local villagers, has been muted. The site was in fact virgin farmland — adjacent to, rather than within, the proposed Wynyard busi- ness park — and was outside the Cleve- land structure plan for industrial use, but Hall's power of persuasion demolished that normally formidable obstacle in less than three weeks. The farmers affected are said to have been dispatched in four days, with cheques large enough to stop them complaining.

The only last-minute hitch was at the Department of Trade and Industry which, despite Mr Heseltine's trumpetings, had to have its arm twisted to come up with the final figure of £58 million of Regional Selective Assistance. Together with local grants, this produced a total of almost £80 million, or £26,000 per job, of public money to tempt Samsung. Some commen- tators objected, seeing unfairness in the way money is thown at foreign investors, but not at struggling indigenous firms: Swan Hunter was in its death-throes (The swansong of a great industry', 29 October 1994) on the very day that Hall was clinch- ing the deal by entertaining the Koreans in his box at St James's Park for the Newcas- tle-Bilbao match, complete with black and white hats and scarves for everyone.

But public money is still available for British firms, so long as they are expanding rather than failing. The problem is that tal- ented people like the Halls want to build shopping centres and golf courses rather than reinvigorate businesses which are the relics of the era of people like the London- derrys. So we must rely on people like the Lees to come here and create manufactur- ing industries for us anew.

In his county guide to Durham written in the late 1940s, Sir Timothy Eden records that 'generally through failure of the heir male', Wynyard had passed through the families of Langton, Conyers, Claxton, Blakiston, Davison and Rudd before it came into the hands of the Tempests, and that these families and others had danced `as it were, a pleasant country dance through the ages, shifting and changing .' as landholdings were bought and sold, other interests gained and lost. In a mood of post-war gloom he lamented: The man- sions are down or derelict — the pavane is over,' but he was wrong: new families, from further afield, were waiting to join the dance. Others, still unheard-of, will take up the step in decades to come. That is how capitalism works and Wynyard is one man- sion to which the process of change has given remarkable new life.

Previous page

Previous page