BEING PRESIDENT IS NOT ENOUGH

For Michael Heseltine, power is not a means to an end: it is an end

in itself, argues Noel Malcolm IN APRIL 1967, a young property develop- er turned politician, Michael Ray Dibdin Heseltine, was obliged to rehouse one of his buyers after 23 faults had been found in the house he had just sold him. 'Further faults in the structure have come to light,' noted the buyer, a Kent schoolmaster, `including my falling through the staircase.' It had not taken long for the purchaser to notice that all was not as it seemed. 'A week after moving into the new house came downstairs, admired the shine on the parquet floor, and stepped from the bot- tom stair into an inch of water.'

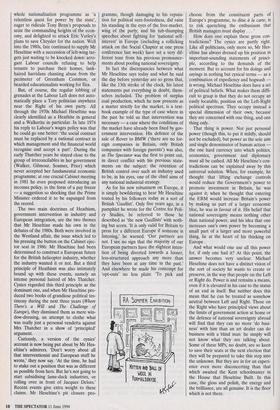

Senior Conservatives may find some hidden symbolism in this story as they consider whether or not to buy a brand- new leadership bid from Mr Heseltine. After a whole series of humiliations at the polls, the thought of a change of prime minister can only come as wel- come relief. What better way of putting new gloss and sparkle into this worn-out Con- servative Government, and who more glossy than Mr Hes- eltine? And yet, at the back of their minds, many Tories feel that the sparkle would prove deceptive. After spending a few weeks admiring the shine on their new prime minister, they might eventually step off the bottom stair and dis- cover that what they thought was ebullient brilliance was only the political equivalent of defective plumbing. For many of his colleagues, the slightly unreal quality of Mr Heseltine is one of his greatest assets. He has a sense of his own mission which, even though it borders on the preposterous, surrounds him like an aura and sets him apart from the common run of jobbing politicians. As one Tory backbencher puts it, 'Michael has a special kind of personal magnetism: he's so colos- sally attracted to himself.' It is this, not just his long experience of government, that makes him one of the few so-called 'big beasts' in the political jungle. And now that the Labour Party is going to be led by a fresh-faced, doe-eyed young man (already christened `Bambi' at Westminster), the appeal of a big beast can only be enhanced, not diminished, in the minds of many on the Tory benches.

For Michael Heseltine is, in a strange way, a politician's politician. The some- times gross histrionics of his performance, which may alienate thoughtful voters, are one aspect of his politics with which most MPs can feel at ease. Cold analysis of his barnstorming party conference speeches suggests that they demonstrate the exis- tence of an inverse square law between content and volume; many of his col- leagues, while recognising this, still feel nothing but envy for the result. (The phrase 'Michael knows how to find the cli- toris of the Conservative Party' has been attributed to more than one senior Tory.) When Mr Heseltine rises to speak in one of the big set-piece debates in the Com- mons, his backbenchers have the pleasant sensation of passengers in a powerful car being taken out for a spin, compared with which a speech by the Prime Minister can still sometimes feel like a test drive in a Reliant Robin. And few would deny that the President of the Board of Trade is one of the Government's best performers on Question Time and other such programmes, where he succeeds in being fluent, combative and generally gaffe-free.

Yet Michael Heseltine knows that these qualities, though considerable, are not enough. To exploit the rules of the political game in conference halls and television stu- dios is one thing; to be in charge of a gov- ernment, setting the ultimate rules of policy by which the whole party must then play, is a different thing altogether. The content of his programme matters (or should matter) just as much as the style of his performance.

Of course there will always be some who, knowing his programme and disagreeing with it, will still vote for him as leader on the grounds that his performance is that of an 'election-winner': some notable ideological non- Heseltinians, such as Nigel Lawson, voted for him on those grounds in November 1990. But a large slice of the parliamentary party — mone- tarists, free-marketeers and Euro-sceptics — remains hos- tile or at best unconvinced. Although Mr Heseltine cannot expect them to believe that he thinks just as they do, he does need to persuade them that he is closer to their position than Kenneth Clarke will ever be. Is he, at the very least, a man the Right can do business with?

Sometimes when interviewers put this question to Mr Heseltine, a pained how- could-you-ask-such-a-thing look comes into his eyes. Was he not in the forefront of government during the heroic early Thatcher years? And even before that, did he not make his name in Parliament by attacking government interference in industry?

It is true that in both government and opposition during the 1970s Mr Heseltine was given some very easy Labour targets to attack. He held a succession of posts to do with transport, aerospace, ship-building and trade and industry at a time when Labour was trying to nationalise everything that moved. He was happy to denounce the whole nationalisation programme as 'a relentless quest for power by the state', eager to ridicule Tony Benn's proposals to seize the commanding heights of the econ- omy, and delighted to attack Eric Varley's plans to save Chrysler for the nation. Well into the 1980s, fate continued to supply Mr Heseltine with a succession of left-wing tar- gets just waiting to be knocked down: arro- gant Labour councils refusing to help tenants to purchase their homes, lank- haired harridans chanting abuse from the perimeter of Greenhorn Common, or bearded educationalists working for Ilea.

But, of course, the regular lobbing of grenades at the Labour Left does not auto- matically place a Tory politician anywhere near the Right of his own party. All through the 1970s Michael Heseltine was clearly identified as a Heathite in general and a Walkerite in particular. In late 1974 his reply to Labour's wages policy was that he could go one better: 'the social contract must be replaced by a national contract in which management and the financial world recognise and accept a part'. During the early Thatcher years he stayed close to the group of irreconcilables in her government (Walker, Gilmour, Soames, Prior) which never accepted her fundamental economic programme; at one crucial Cabinet meeting in 1981 he even proposed introducing an incomes policy, in the form of a pay freeze — a suggestion so shocking that the Prime Minister ordered it to be expunged from the record.

The two main doctrines of Heathism, government intervention in industry and European integration, are the two themes that Mr Heseltine made his own in the debates of the 1980s. Both were involved in the Westland affair, the issue which led to his pressing the button on the Cabinet ejec- tor seat in 1986: Mr Heseltine had been determined to construct a European future for the British helicopter industry, whether the industry wanted it or not. But a third principle of Heathism was also intimately bound up with these events, namely an intense personal hatred of Mrs Thatcher. Cynics regarded this third principle as the dominant one, and when Mr Heseltine pro- duced two books of grandiose political tes- timony during the next three years (Where There's a Will and The Challenge of Europe), they dismissed them as mere win- dow-dressing, an attempt to clothe what was really just a personal vendetta against Mrs Thatcher in a show of 'principled' argument.

Curiously, a version of the cynics' account is now being put about by Mr Hes- eltine's admirers. 'Don't worry about all that interventionist and European stuff he wrote,' they now say. 'At the time, he had to stake out a position that was as different as possible from hers. But he's not going to start subsidising lame-duck industries, or rolling over in front of Jacques Delors.' Recent events give extra weight to these claims. Mr Heseltine's pit closure pro- gramme, though damaging to his reputa- tion for political sure-footedness, did raise his standing in the eyes of the free-market. wing of the party; and his tub-thumping speeches about fighting for 'national self- interest' in Europe (including a rollicking attack on the Social Chapter at one press conference last week) have set a very dif- ferent tone from his previous pronounce- ments about pooling national sovereignty.

In fact the discrepancies between what Mr Heseltine says today and what he said the day before yesterday are so gross that, like the 13th stroke of the clock, his latest statements put everything in doubt, them- selves included. The problem of surplus coal production, which he now presents as a matter strictly for the market, is a text- book example of the type of case where in the past he told us that intervention was necessary — a case where the conditions of the market have already been fixed by gov- ernment intervention. His defence of the sale of Rover to BMW (`there are no for- eign companies in Britain, only British companies with foreign parents') was also, as The Spectator was the first to point out, in direct conflict with his previous state- ments on the subject: the retention of British control over such an industry used to be, in his eyes, one of the chief aims of any national industrial strategy.

As for his new robustness on Europe, it is simply bewildering to hear Mr Heseltine touted by his followers today as a sort of British 'Gaullist'. Only five years ago, in a pamphlet he wrote for the Centre for Poli- cy Studies, he referred to those he described as 'the new Gaullists' with noth- ing but scorn. 'It is only valid for Britain to press for a different Europe if someone is listening,' he warned. 'Our partners are not. I see no sign that the majority of our European partners have the slightest inten- tion of being diverted towards a looser, less-structured approach any more than they have been at any time in the past.' And elsewhere he made his contempt for `opt-outs' no less plain: `To pick and choose from the constituent parts of Europe's programme, to dine a la carte, is to risk quenching the enthusiasm that British managers must display . . . '

How does one explain these gross con- tradictions? The cynics are partly right. Like all politicians, only more so, Mr Hes- eltine has always dressed up his position in important-sounding statements of princi- ple, according to the demands of the moment. But to account for his doings and sayings in nothing but cynical terms — as a combination of expediency and hogwash is wrong. Michael Heseltine does have a set of political beliefs. What makes them diffi- cult to grasp is that they do not occupy an easily locatable, position on the Left-Right political spectrum. They occupy instead a special dimension of their own, because they are concerned with one thing, and one thing only.

That thing is power. Not just personal power (though this, to put it mildly, should not be excluded), but power as the sole aim and single denominator of human action — the one hard currency into which politics, economics, government and diplomacy must all be cashed. All Mr Heseltine's con- tradictions can be explained away by this universal solution. When, for example, he thought that lifting exchange controls would reduce the Government's power to promote investment in Britain, he was against it; when he thought that entering the ERM would increase Britain's power by making us part of a larger economic bloc, he was in favour of it. His belief that national sovereignty means nothing other than national power, and his idea that one increases one's own power by becoming a small part of a larger and more powerful thing, lie at the heart of his thinking on Europe .

And what would one use all this power for, if only one had it? At this point, the answer becomes very unclear. Michael Heseltine does not have a distinct vision of the sort of society he wants to create or preserve, in the way that people on the Left or Right do. Power is and remains a means, even if it is elevated in his case to the status of an end in itself. But neither does this mean that he can be treated as somehow neutral between Left and Right. Those on the Right who have principled views about the limits of government action at home or the defence of national sovereignty abroad will find that they can no more `do busi- ness' with him than an art dealer can do business with a blind man: he simply will not know what they are talking about. Some of these MPs, no doubt, are so keen to save their seats at the next election that they will be prepared to take this step into the unknown. But they are in for an experi- ence even more disconcerting than that which awaited the Kent schoolmaster in the House that Heseltine Built. In this case, the gloss and polish, the energy and the brilliance, are all genuine. It is the floor which is not there,

Previous page

Previous page