CINEMA

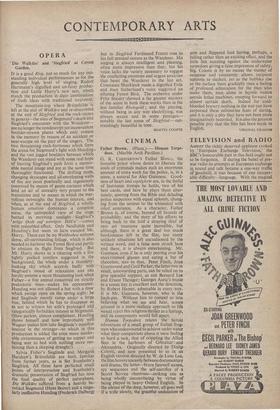

Father Brown. (Plaza.)—Human Torpe- does. (Marble Arch Pavilion.) G. K. CHESTERTON'S Father Brov.ii, the loveable priest whose desire to liberate the souls of criminals makes such an enormous amount of extra work for the police, is, in a sense, a natural for Alec Guinness. Good- ness of heart and espieglerle are, in the fistful of histrionic trumps he holds, two of his best cards, and here he plays them alter- nately, quoting from the Bible and deluding police inspectors with equal aplomb, chang- ing from the serious to the whimsical with oiled' assurance. As a character, Father Brown is, of course, beyond all bounds of probability, and the story of his efforts to bring back to the fold a straying thief of rare art treasures quite incredible, but although there is a great deal too much bookishness left in the film, too many unlikely situations left uncushioned by the written word, and a false note struck here and there, it is always entertaining. Mr. Guinness, even if he is only peering over his steel-rimmed glasses and eating a bar of chocolate, sees to that. Peter Finch, Joan Greenwood and Cecil Parker, the latter two in small, unrewarding parts, can be relied on to give splendid support, as can Bernard Lee and Ernest Thesiger; Georges Auric's music in a comic key is excellent and the direction, by Robert Hamer, admirable in every way. It is Mr. Guinness, however, who is the linch-pin. Without him to compel us into believing what we see and hear, senses attuned to a more realistic approach to life would reject this religious thriller as a fantasy, and its components would fall apart. '

Human Torpedoes relates the heroic adventures of a small group of Italian frog- men who endeavoured to achieve under water what their compatriots above it were finding so hard a task, that of crippling the Allied fleet in the harbours of Gibraltar and Alexandria. Originally directed by Diulip Colotti, and now presented to us in an English version directed by W. de Lane Lea, the film hovers uneasily between documentary and drama, the latter—brave farewell scenes, spy sequences and the self-sacrifice of a Secret Service chanteuse—striking one as being wholly unconvincing by virtue of being played in heavy Oxford English. In the silence of the deep, however, all goes well if a trifle slowly, the graceful undulation of arm and flippered foot having, perhaps, lulling rather than an exciting effect, and the little fish nuzzling against the underwater torpedoes giving a false impression of safety. Sig. Colotti is by no means the master of suspense and constantly allows incipient tensions to slacken, yet as the bubbles rise to the surface there gradually rises a feeling of profound admiration for the men who make them, men alone in hestile waters astride lethal machines, creeping forward to almost certain death. Indeed for cold- blooded bravery nothing in the war can have surpassed these submarine feats of daring, and it is only a pity they have not been more imaginatively recorded. It is also the greatest possible pity that the film has been made in English. VIRGINIA GRAHAM

Previous page

Previous page