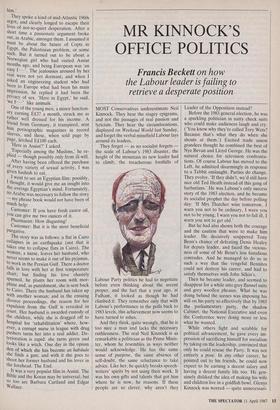

MR KINNOCK'S OFFICE POLITICS

Francis Beckett on how

the Labour leader is failing to retrieve a desperate position

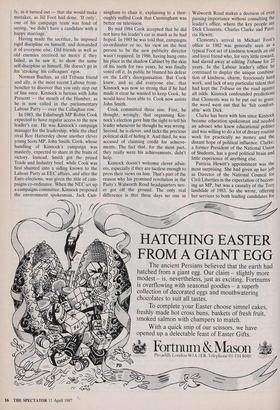

MOST Conservatives underestimate Neil Kinnock. They hear the stagey epigrams, and not the passages of real passion and lyricism. They hear the circumlocutions, displayed on Weekend World last Sunday, and forget the verbal minefield Labour lays around its leaders.

They forget — as no socialist forgets — the scale of Labour's 1983 disaster, the height of the mountain its new leader had to climb, the treacherous foothills of Labour Party politics he had to negotiate before even thinking about the ascent proper, and the fact that a year ago, at Fulham, it looked as though he had climbed it. They remember only that with Labour's performance in the polls back to 1983 levels, this achievement now seems to have turned to ashes.

And they think, quite wrongly, that he is too nice a man and lacks the necessary ruthlessness. The real Neil Kinnock is as remarkable a politician as the Prime Minis- ter, whom he resembles in ways neither would acknowledge. He has the same sense of purpose, the same absence of self-doubt, the same reluctance to take advice. Like her, he quickly breaks speech- writers' spirits by not using their work. It was his own gifts and talents that got him where he is now, he reasons. If these people are so clever, why aren't they Leader of the Opposition instead?

Before the 1983 general election, he was a sparkling politician in natty check suits who could make audiences laugh and cry.

(`You know why they're called Tory Wets? Because that's what they do when she shouts at them.') Excited trade union grandees thought he combined the best of Nye Bevan and Lloyd George. He was the natural choice for television confronta- tions. Of course Labour has moved to the Left, he admitted disarmingly in response to a Tebbit onslaught. Parties do change.

They evolve. 'If they didn't, we'd still have nice old Ted Heath instead of this gang of barbarians.' He was Labour's only success story of the 1983 election, and he became its socialist prophet the day before polling day: 'If Mrs Thatcher 'wins tomorrow, I warn you not to be ordinary, I warn you not to be young, I warn you not to fall ill, I warn you not to get old.'

But he had also shown both the courage and the caution that were to make him leader. He decisively scuppered Tony Benn's chance of defeating Denis Healey for deputy leader, and faced the vicious- ness of some of Mr Benn's less fastidious comrades. And he managed to do so in such a way that the vengeful Bennites could not destroy his career, and had to satisfy themselves with John Silkin's.

Then he became leader, and seemed to disappear for a while into grey flannel suits and grey woollen phrases. What he was doing behind the scenes was imposing his will on his party so effectively that by 1985 the parliamentary party, the shadow Cabinet, the National Executive and even the Conference were doing more or less what he wanted.

While others fight and scrabble for political advancement, he gave every im- pression of sacrificing himself for socialism by taking on the leadership, convinced that only he could rescue the Party. It was not entirely a pose. In any other career, he pointed out to his friends, he could now expect to be earning a decent salary and having a decent family life too. He gen- uinely disliked the idea of making his wife and children live in a goldfish bowl. Glenys Kinnock was worred — quite unnecessari- ly, as it turned out — that she would make mistakes, as Jill Foot had done. 'If only', one of his campaign team was fond of saying, 'we didn't have a candidate with a happy marriage.'

Having made the sacrifice, he imposed rigid discipline on himself, and demanded it of everyone else. Old friends as well as old enemies received no mercy if they failed, as he saw it, to show the same self-discipline as himself. He doesn't go in for 'stroking' his colleagues' egos.

Norman Buchan, an old Tribune friend and ally, is the most recent Labour front- bencher to discover that you only step out of line once. Kinnock is furious with John Prescott — the mouth of the Humber, as he is now called in the parliamentary Labour Party — over the Callaghan row.

In 1983, the Edinburgh MP Robin Cook expected to have regular access to the new leader's ear. He was Kinnock's campaign manager for the leadership, while the chief rival Roy Hattersley chose another clever young Scots MP, John Smith. Cook, whose handling of Kinnock's campaign was masterly, expected to share in the fruits of victory. Instead, Smith got the prized Trade and Industry brief, while Cook was first shunted into a siding known to the Labour Party as EEC affairs, and after the Euro-elections, was given the title of cam- paigns co-ordinator. When the NEC set up a campaigns committee, Kinnock proposed the environment spokesman, Jack Cun- ningham to chair it, explaining to a thor- oughly miffed Cook that Cunningham was better on television.

By mid 1984 Cook accepted that he did not have his leader's ear as much as he had hoped. In 1985 he was told that, campaigns co-ordinator or no, his view on the best person to be the new publicity director wasn't required. In 1986, having hung onto his place in the shadow Cabinet by the skin of his teeth for two years, he was finally voted off it. In public he blamed his defeat on the Left's disorganisation. But Cook knew, and so did everyone else, that Kinnock was now so strong that if he had made it clear he wanted to keep Cook, he would have been able to. Cook now assists John Smith.

Cook committed three sins. First, he thought, wrongly, that organising Kin- nock's election gave him the right to tell his leader whenever he thought he was wrong. Second, he is clever, and lacks the precious political skill of hiding it. And third, he was accused of claiming credit for achieve- ments. The fact that, for the most part, they really were his achievements, didn't help.

Kinnock doesn't welcome clever aduis- ers, especially if they are tactless enough to press their views on him. That's part of the reason why his promised revolution in the Party's Walworth Road headquarters nev- er got off the ground. The only real difference is that these days no one in Walworth Road makes a decision of even passing importance without consulting the leader's office, where the key people are Dick Clements, Charles Clarke and Patri- cia Hewitt.

Clements's arrival in Michael Foot's office in 1982 was generally seen as a typical Foot act of kindness towards an old and loyal friend who, for very little reward, had slaved away at editing Tribune for 22 years. In the Labour leader's office he continued to display the unique combina- tion of kindness, charm, ferociously hard work, and lack of any particular talent that had kept the Tribune on the road against all odds. Kinnock confounded predictions that Clements was to be put out to grass: the word went out that he 'felt comfort- able' with Dick.

Clarke has been with him since Kinnock became education spokesman and needed an adviser who knew educational politics and was willing to do a lot of dreary routine work for practically no money and the distant hope of political influence. Clarke, a former President of the National Union of Students, has a good political brain and little experience of anything else. Patricia Hewitt's appointment was the most surprising. She had given up her job as Director of the National Council for Civil Liberties in the expectation of becom- ing an MP, but was a casualty of the Tory landslide of 1983. So she wrote, offering her services to both leading candidates for the leadership. Roy Hattersley didn't rep- ly, but Kinnock took her on board. When his election was all over bar the shouting, several media professionals were urged on him as press officer. Kinnock let it be know that he wanted a 'user of the media' and appointed Hewitt. His experience of media professionals wasn't always happy. They tended to be ruthless with his often over-long press statements.

To politicians, talent in colleagues is often seen as a threat, rather than a resource to be used. Even where it's presented to them on a plate, they do not know how to use it, because successful politicians become MPs very young, with- out having done a real job or having learned how to manage other talented people. Neil Kinnock is a thoroughly pro- fessional politician, with all the strengths and weaknesses of his kind. Everything that one man's force of personality and determination can achieve, Neil Kinnock will deliver for his party.

Previous page

Previous page