Believing the unbelievable

Tokyo First, a statement of personal interest. As

a frequent traveller in Asia, a sometime Passenger of Korean Air Lines and a regular voyager along Romeo 20, the now-famous air route across the north Pacific, I am no friend of those who shoot at or shoot down c, Iva airlines going peacefully about their °osiness. The sad end of KAL's flight 007, and the by now certain deaths of all 269 aboard, is not only shocking in itself, but 'here s

a further dimension, even more alarming: it stemmed somehow from the rivalry between parties who have it in then- Power to shoot down Planet Earth itself. On neither side is there, apparently, any doubt about who are the guilty men. 'The murder of innocent civilians is a serious in- ternational issue between the Soviet Union and civilised people everywhere who cherish Individual rights and value human life,' said Ronald Reagan, his voice resonant with Practised indignation. 'Who sent this plane to Soviet air space and for what purpose? boomed Tass in Moscow, their nameless c°InInentator speaking in the harsh, Metallic tone used elsewhere by talking .!c'cics and weighing machines. 'Does Mr rresident believe that the very concept of national sovereignty no longer exists, and °lie may intrude with impunity into the air sPace of independent states?'

In content, as well as tone, this pair of Propositions frame the conflict. The American case for the prosecution is that

KAL flight 'strayed' innocently, which Tust mean unwittingly, and that the Rus- sians downed it deliberately, that is, know- 1_08 that it was an airliner and nothing more. No. evidence has yet been made public which confirms confirms, beyond reasonable doubt, either of these assertions, except the treacherous argument that it has to be that Way, because anything else is unthinkable. Srnmetrical as the other bookend, the Russians charge that the aircraft must have overflown their territory deliberately,

the culpably, which would give them

h

e right (and, as good Soviet airmen, the duty) to shoot it down. Despite a brisk and Soviets search for wreckage, the viets have so far offered no proof, either, except the argument that any other explana- tion s unthinkable.

.von at this point we can decide, without ".esItation, that the evidence so far pro- duced is insufficient, with some key part of 1-?e Puzzle still missing. Given that some Clues are, very likely, scattered over the Sea of Okhotsk with the wreckage of the air- craft, it may well be that the whole truth 7111 never be known — for whichever side Inds evidence will be accused of falsifying

it by the other, and we have no neutrals here. This does not mean, however, that we can learn nothing about superpower behaviour under stress — the most dangerous ingredient of the whole hair- raising story.

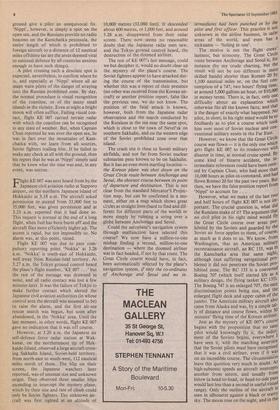

Back, then, to the Via Dolorosa of the north Pacific. At 2.07 a.m. on the morning of 1 September (Japanese time, which is also local time at the point the aircraft is presumed shot down) Korean Air Lines Flight KE 007 reported itself by radio to Narita airport, near Tokyo, as being at the .compulsory reporting point called `Nippi' south-east of the Kamchatka peninsula, proceeding south-west. KE 007 was due to proceed to the compulsory reporting point `Nokka' south-east of the Japanese island of Hokkaido, and from there to cross the Japanese archipelago to reach its home base, Seoul, shortly after dawn.

The report that KE 007 had reached was, as we now know, false. The Soviets charge that the aircraft had already been flying for nearly an hour over their air space, and the American Secretary of State, George Shultz, says the aircraft was shadowed by Soviet fighters for two and a half hours before it was shot down, which, given the distances and times involved, amounts to the same thing.

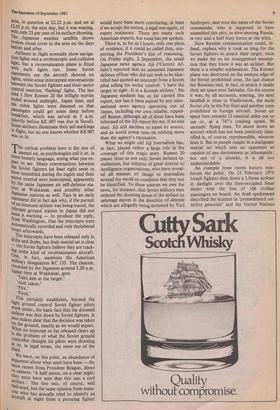

Flight KE 007 did not, therefore, stick to the course, Romeo 20, filed by the pilot-in- command, Chun Byung-in, before the air- craft left Anchorage, nor was the flight at reporting point 'Nippi' when Captain Chun radioed Tokyo that it was. Were these errors deliberate, or were they accidents? Flight KE 007 was a jumbo jet, a Boeing 747 fitted, like all copies of this aircraft, with a Litton industries triple inertial navigation system. This works with three independent gyroscopes which together guide the aircraft, via a computer, advanc- ing it through a series of map co-ordinates punched in by the pilot and, according to airline rules, checked by the co-pilot. The copy of his flight plan left by Chun at Anchorage shows him passing through all 12 of the compulsory reporting points be- tween Anchorage and Seoul, his destination.

Readers familiar with navigation will recognise the inertial navigation system as a sophisticated form of dead reckoning, as used by Captain C. Columbus and all his successors. This is based on the syllogism that an aircraft (or ship, or any other vehicle) proceeding on a known course at a known speed must arrive at a predictable point at a given time. No seaman or airman who knows his business will rely on any form of dead reckoning without obtaining, as often as conditions permit, a 'fix', an in- dependent sighting which establishes his position with reference to something out- side his ship or plane — the sun, a star, a coastline, a lighthouse or a radio beacon. The compulsory reporting points of air routes are also compulsory fixes, confirm- ing to ground control that the aircraft is both on course and on time.

Most compulsory reporting points are over towns, where radio beacons on the ground give a pilot an unequivocal fix. `Nippi', however, is simply a spot on the open sea, and the Russians provide no radio beacons on the Kamchatka peninsula, the entire length of which is prohibited to foreign aircraft to a distance of 12 nautical miles offshore (as are the areas deemed vital to national defence by all countries anxious enough to have such things).

A pilot crossing such a desolate spot is expected, nevertheless, to confirm where he is, and especially at `Nippi' where all air maps warn pilots of the danger of straying into the Russian prohibited zone. By day, the normal procedure is visual recognition of the coastline, or of the many small islands in the vicinity. Even at night a bright moon will often suffice. Failing visual con- tact, flight KE 007 carried terrain radar with which the coastline can be recognised in any state of weather. But, when Captain Chun reported he was over the open sea, he was in fact over the mountains of Kam- chatka with, we learn from all sources, Soviet fighters trailing him. If he failed to make any check at all with the ground, then his report that he was at `Nippi' simply said that he knew what the time was and, in any event, was untrue.

Flight KE 007 was next heard from by. the Japanese civil aviation radio at Sapporo airport, on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido at 3.18 a.m. The aircraft asked permission to ascend from 33,000 feet to 35,000 feet, was given permission and at 3.23 a.m. reported that it had done so. This request is normal at the end of a long flight, when fuel has been burnt off and the aircraft flies more efficiently higher up. The ascent is rapid, but not impossibly so. No alarm was, at this point, raised.

Flight KE 007 was due to pass com- pulsory reporting point `Nokka' at 3.26 a.m. `Nokka' is south-east of Hokkaido, well away from Russian-held territory. At 3.27 a.m. the Tokyo ground control heard the plane's flight number, 'ICE 007 ... ' but the rest of the message was drowned in noise, and all radio contact was lost a few minutes later. It was the failure of Tokyo to make further contact which alerted the Japanese civil aviation authorities (in whose control area the aircraft was assumed to be) to raise the alarm, and the first air-sea rescue search was begun, but soon after abandoned, in the `Nokka' area. Until the last moment, in other words, flight KE 007 gave no indication that it was off course.

However, at 3.20 a.m. the Japanese air self-defence force radar station at • Wak- kanai, on the northernmost tip of Hok- kaido Island, observed a large aircraft cross- ing Sakhalin Island, Soviet-held territory, from north-east to south-west, 112 nautical miles north of them. The blip on their screen, the Japanese watchers later reported, was of unusual size and unknown origin. They observed three smaller blips ascending to intercept the mystery plane, which by their size and rate of climb could only be Soviet fighters. The unknown air- craft was first sighted at an altitude of

10,000 metres (32,000 feet). It descended about 600 metres, or 1,000 feet, and around 3.28 a.m. disappeared from their radar screen. There now seems no reasonable doubt that the Japanese radar men saw, and the Tokyo ground control heard, the destruction of the doomed airliner.

The rest of KE 007's last message, could we but decipher it, would no doubt clear up the mystery of the plane's course. The Soviet fighters appear to have attacked dur- ing the course of the transmission, but whether this was a report of their presence (no other was received from the Korean air- craft) or another position report, false like the previous one, we do not know. The position of the fatal attack is known, however, both from the Japanese radar observation and the search conducted by the Russians in the sea near the same spot, which is close to the town of Nevel'sk on southern Sakhalin, and on the western edge of the Soviet prohibited zone over that island.

The crash site is close to Soviet military airfields, and not far from Soviet nuclear submarine pens known to be on Sakhalin. But it has an even more startling location — the Korean plane was shot down on the Great Circle route between Anchorage and Seoul, the shortest course between its point of departure and destination. This is not clear from the standard Mercator' Projec- tion map, but can be confirmed in a mo- ment, either on a map which shows great circles as straight lines (hard to find and dif- ferent for different parts of the world) or more simply by running a string over a globe between Anchorage and Seoul.

Could the aeroplane's navigation system through malfunction have selected this course? We now have a million-to-one mishap finding a second, million-to-one destination — where the doomed airliner was in fact headed, if not by that route, The Great Circle course would have, in fact, been automatically selected by the plane's navigation system, if only the co-ordinates of Anchorage and Seoul and no in- termediates had been punched in by the pilot and first officer. This practice is not unknown in the airline business, in safer areas of the world, and even has a nickname — 'holing in one'. The motive is not the flight crews' laziness, but economy. The Great Circle route between Anchorage and Seoul is, for instance (by my crude charting, but the result will not be too different in more skilled hands) shorter than Romeo 20 by 1,100 nautical miles or, on the fuel con- sumption of a 747, two hours' flying time, at around 5,000 gallons an hour, or $10,00° in money terms. There is, in fact, only one difficulty about an explanation which otherwise fits all the known facts, and that is the danger of exactly what happened. No pilot, in short, in his right mind would be so foolhardy as to plot a course which took him over most of Soviet nuclear and con- ventional military assets in the Far East. However, we know that the Great Circle course was flown — it is the only one which gets flight ICE 007 to its rendezvous with disaster in time, at normal cruise speed. BY some kind of bizarre accident, the in- termediate references could have been omit- ted by Captain Chun, who had more than 10,000 hours as pilot-in-command, and had flown Romeo 20 for the past two years. But then, we have the false position report from `Nippi' to account for. . . However, what we make of the last two and half hours of flight KE 007 is not MI- portant. The crucial question is, what did the Russians make of it? The argument that no civil pilot in his right mind would flY the Great Circle course over areas pro- hibited by the Soviets and guarded by the Soviet air force applies to them, of course, as much as it does to us. We know, from Washington, that an American militarY reconnaissance aircraft, an RC 135, was in the Kamchatka area that same night, although (not suffering navigational Pr(/' blems) it did not penetrate the Soviet pro- hibited zone. The RC 135 is a converted Boeing 707 (which itself started life as a military design, the flying tanker KC 135). The Boeing 747 is an enlarged 707, the easY discrimination points being size, and the enlarged flight deck and upper cabin of the jumbo. The American military aircraft also came from Alaska and was, by a simple tal- ly of distance and course flown, within 30 minutes' flying time of the Korean airliner. Just as the mystery of KE 007's course begins with the proposition that no sane pilot would knowingly fly it, the indict- ment of the Soviets begins, everywhere I have seen it, with the matching assertion that the Soviet pilots must have recognised that it was a civil airliner, even if it was on an incredible course. The circumstance's leave this question very much in doubt. At high-subsonic speeds an aircraft intercepts another from astern, and usually

from below (a head-to-head, or head-to-side pass would last less than a second in useful visual range). Only the outline of the aircraft is seen in silhouette against a black or starry sky. The moon rose on the night, and in the area, in question at 22.32 p.m. and set at 12.07 p.m. the next day, but it was waning, with only 23 per cent of its surface showing. The Japanese weather satellite shows broken cloud cover in the area on the days before and after.

Airliners in flight normally show naviga- tion lights and a stroboscopic anti-collision light, but a reconnaissance plane is fitted with such lights too. Some Soviet statements say the aircraft showed no lights, while some intercepted conversations between the Soviet fighters and their sector control mention 'flashing' lights. The last time I flew Romeo 20 the inflight movies ended around midnight, Japan time, and the cabin lights were dimmed so that Passengers could get some sleep before breakfast, which was served at 5 a.m. (shortly before KE 007 was due in Seoul). Some airliners illuminate their tail markings in flight, but no one knows whether KE 007 was so lit.

The critical problem here is the one of mental set, as psychologists call it or, in more homely language, seeing what you ex- Peet to see. Many conversations between the Soviet fighters (at least eight seem to have scrambled during the night) and their sector control were intercepted, apparently bY the same Japanese air self-defence sta- tion at Wakkanai, and possibly other ''aPanese stations as well. Tass in an early statement did in fact ask why, if the pursuit of an innocent airliner was being traced, the :relevant ground station in Japan did not issue a warning — to produce the reply, from Washington, that the intercepts were automatically recorded and only deciphered hours afterwards. The intercepts have been released only in dribs and drabs, but their mental set is clear -- the Soviet fighters believe they are track- ing some kind of reconnaissance aircraft. One, in fact, mentions the American military designation RC 135. The clearest, recorded by the Japanese around 3.20 a.m. Japan time at Wakkanai, goes

• 'Take aim at the target.' 'Aim taken.' 'Fire.'

'Fired.'

„ This certainly establishes, beyond the tight ground control Soviet fighter pilots Work under, the basic fact that the doomed airliner was shot down by Soviet fighters. It also makes clear that the decision was taken Ori the ground, exactly as we would expect. What no intercept so far released clears up is the problem of what the Soviet ground controller thought his pilots were shooting at or, in legal terms, the mens rea of the deed.

We have, on this point, an abundance of argument about what must have been — the niost recent from President Reagan, direct to camera: 'A half moon, on a clear night; they must have seen that this was a civil airliner.' The line was, of course, well delivered, but the same opinion from some- 01e who has actually tried to identify an aircraft at night from a pursuing fighter

would have been more convincing, at least if we accept the notion, a legal one again, of expert testimony. There are many such American experts, but none has yet spoken.

There is, as far as I know, only one piece. of evidence, if it could be called that, sup- porting the President's line of reasoning. On Friday night, 2 September, the small Japanese news agency Jiji ('Current Af- fairs') reported that an unnamed Japanese defence officer who did not wish to be iden- tified had quoted an intercept from a Soviet pilot telling his sector control: 'I have the target in sight. It is a Korean airliner.' No Japanese medium has so far carried this report, nor has it been moved by any inter- national news agency operating out of Japan, including our own reliable, ripped- off Reuter, although all of them have been informed of the Jiji report (by me, if no one else). Jiji still declines to name its source, and its world scoop rests on nothing more than the agency's reputation.

What we might call Jiji Journalism has, in fact, played rather a large role in the coverage of this tragic story. Romeo 20 passes close to not only Soviet defence in- stallations, but subjects of great interest to intelligence organisations, who have reveal- ed all manner of things to journalists around the world on condition that they not be identified. To these sources we owe the news, for instance, that Soviet military men ordered the shooting down of the airliner to sabotage moves in the direction of détente which are allegedly being mounted by Yuri Andropov, and even the name of the Soviet commander who is supposed to have assembled this plot, in slow-moving Russia, in two and a half busy hours at the telex.

Slow Russian communication could, in- deed, explain why it took so long for the Soviet fighters to attack their target, once we make the so far unsupported assump- tion that they knew it was an airliner. But there is a simpler explanation. The Korean plane was destroyed on the western edge of the Soviet prohibited zone, the last chance the Russians had, in fact, to attack it inside their air space over Sakhalin. On the course it was, by all accounts, steering, the next landfall is close to Vladivostok, the main Soviet city in the Far East and another zone prohibited to foreign aircraft. Soviet air space here extends 12 nautical miles out to sea or, at a 747's cruising speed, 90 seconds' flying time. To shoot down an aircraft which has not been positively iden- tified is, of course, reprehensible, whoever does it. But in people caught in a malignant mental set which sees an opponent as capable of any deviousness or inhumanity, but not of a mistake, it is all too understandable.

An example from recent history rein- forces the point. On 21 February 1973 Israeli fighters shot down a Libyan airliner in daylight over the then-occupied Sinai desert with the loss of 106 civilian passengers on board. An Arab spokesman described the incident as 'premeditated col- lective genocide' and the United Nations Secretary General, Kurt Waldheim, called it 'one of the most shocking incidents in the history of civil aviation', The Israeli defence minister, General Moshe Dayan, said that the incident had been caused by three errors: the pilot of the plane, who did not follow orders to land his aircraft, the Cairo airport control tower, which misled the Libyan pilot into thinking he was still over Egyptian territory, and the Israelis for their misinterpretation of the events.

Dayan expressed profound regret, but announced that no inquiry would be held, and none ever has. The Libyan aircraft, ac- cording to Israel radio, was flying over a secret Israeli military installation near the Suez Canal. Dayan, a soldier whose hum- anity I have always admired, was quoted as adding: 'We are in a situation close to war here. We could not afford to take a chance.' No American or Soviet official comment was forthcoming.

I have no doubt, in that case, that Moshe Dayan would have given much to call back 21 February 1973, if such were in human power. Mourning the dead of flight KE 007, we might in charity assume that there are people in Moscow, and possibly Seoul too, who feel the same about 1 September 1983. If no one has learnt anything from this tragedy about the dangers of jumping, let alone jetting, to conclusions, the outlook for Spaceship Earth is grim. In- deed.

Previous page

Previous page