Gilding the Lily

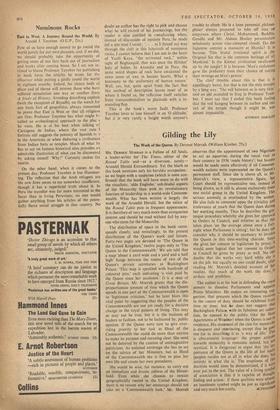

The Work of the Queen. By Dermot Morrah. (William Kimber, 21s.) MR. DERMOT MORRAH iS a Fellow of All Souls, a leader-writer for The Times, editor of the Round Table and—as a diversion, surely— Arundel Herald Extraordinary. Yet the blurb to this book mentions only his heraldic occupation : so we begin with a suspicion (which is soon con- firmed) that, the book will have more to do with the ritualistic, `olde Englishe,' sub-feudal aspects of the Monarchy than with its revolutionary function of leadership in a world-wide Common- wealth. What has been written is largely the work of the Arundel Herald, but the editor of the Round Table puts in frequent appearances. It is therefore of very much more than antiquarian interest and should be read without fail by any- one who cares for the Monarchy.

The distribution of space in the book corre- sponds closely, and revealingly, to the present distribution of the Queen's work and leisure. Forty-two pages are devoted to `The Queen in the United Kingdom,' twelve pages- only to 'The Queen in the Commonwealth.' We are told that a map 'about a yard wide and a yard and a half high' hangs between the rooms of two of the Queen's private secretaries at Buckingham Palace. `This map is speckled with hundreds of coloured pins,' each indicating `a visit paid by the Queen since her accession.' It is a map of Great Britain. Mr. Morrah grants that the dis- proportionate _amount of time which the Queen spends in one part of the Commonwealth is open to `legitimate criticism,' but he later blurs this vital point by suggesting that the peoples of the Commonwealth are not yet ready for a decisive change in the royal pattern of living. This may or may not be true, but it is the business of leaders to fashion, not to be fashioned by, public opinion. If the Queen were now to give over- riding priority to her task as Head of the Commonwealth she could do more than anyone to make its purpose and meaning clear. She need not be deterred by the caution of unimaginative politicians. As national sovereign she has to act on the advice of her Ministers, but as Head of the Commonwealth she is free to plan her own life and create her own precedents.

She would be wise, for instance, to carry out an immediate and drastic reform of the House- hold. Even while she chooses to remain geographically rooted in the United Kingdom, there is no reason why her entourage should not take on a `Commonwealth look.' Mr. Morrah observes that the appointment of two Nigerians to act as equerries during the royal visit to their country in 1956 `made history'; but history

would be made more effectively if all Common- wealth nations were represented on the Queen's

permanent staff. Since she is above all, in Mr.

Morrah's view, a representative figure, her, Court should be representative too, instead of being drawn, as it still is, almost exclusively from one social group in the United Kingdom. This serious anomaly is overlooked by the author. He also fails to comment upon the triviality and irrelevance of much that the Queen does during her working months. Thus he describes the grCe tesque procedure whereby she gives her approval to Orders in Council, and informs us that this takes place `on the average about once a fort- night when Parliament is sitting'; but he does not consider 'why it should be necessary to involve the Queen in this time-wasting charade. Sinee she gives her consent to legislation by proxy, d would seem logical that her consent to Orders in Council be given by proxy as well. No One doubts that she works very hard while she 15 on the job, but equally no one could doubt, after reading Mr. Morrah's detailed account of her routine, that much of the work she does is archaic and profitless.

The author is at his best in defending the royal powers to dissolve Parliaments and appoint Prime Ministers. He makes an interesting sur gestion, that presents which the Queen receives in the course of duty should be exhibited from time to time; but he does not suggest that Buckingham Palace, with its fabulous art collo' tion, be opened t> the public (like the State Apartments at Windsor) when the Queen is not to residence, His statement of the case for monarchy is eloquent and convincing, except that he gO too far in describing it as 'a way of life.' Tills is obscurantist language: the proper attitude, towards monarchy is romantic indeed, but not mystical. It is dangerous to argue that `the IP portance of the Queen in the life of her ma°, peoples resides not at all in what she does, but entirely in what she is.' The emptiness of this doctrine would soon be demonstrated, if it werei ever put to the test. The value of a living synlb, of association is that it is capable of though' feeling and action: if these qualities were absent: an inanimate symbol might be just as significa°1

and very much less costly. Aura

Previous page

Previous page