A GALE FOR ALL SEASONS

The press: Paul Johnson

recalls an oldfriend and former Spectator editor

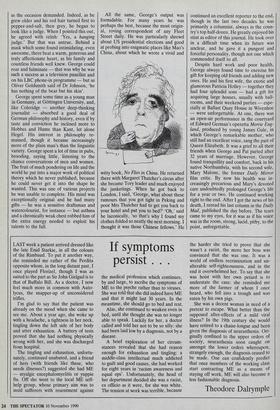

GEORGE Gale belonged to an en- dangered species, the educated journalist. His English was superb: clear, forceful without ever being raucous, plain and terse as a rule, which made his rare flourishes all the more striking. He exercised Hemingway-like restraint in the use of adjectives and adverbs, and skilfully selected the few he did employ. Well-read, widely travelled, thoughtful and opinion- ated by nature, he could write with power and authority on a huge range of heavyweight subjects, yet also deliver sharp-witted judgments on the trivial issues and personalities which daily flash across a newspaper's line of vision. That was why a succession of outstanding editors, Wads- worth of the Guardian, Cudlipp of the Mirror, Christiansen of the Express and English of the Mail, gave his work such prominence. George was an accomplished craftsman. He never missed a deadline, however remote and difficult the assign- ment — he performed wonders during the desperate Congo crisis of 1960 — and however short the time available. He even, with much groaning vituperation, mastered the new technology, and my last glimpse of him, at the Tory Party conference, where we shared a suite at the Carlton, was of a frail, white-haired figure struggling victor- iously with his Tandy.

George was a Northumbrian, a star pupil of that excellent academy, the Newcastle Royal Grammar School. At Peterhouse, Cambridge, he was fortunate to come under the supervision of a formidable historian, Herbert Butterfield, and under the penumbra of a highly original philo- sophical sceptic, Michael Oakeshott. Peterhouse, which has been the principal engine of Conservative thinking in recent decades, was the formative influence in George's intellectual life. 'What was the most important thing you learned at Cam- bridge?' I once asked him. 'That the rule of law is far more important than the vote,' he replied.

Like another fine journalist, William Hazlitt, George's early background was of strick Nonconformity, in his case Pre- sbyterianism. He shook it off as a teenager. walking out of a sermon he judged offen- sively anti-Semitic, and he remained an agnostic for the rest of his life. But, like Hazlitt, he was troubled by memories of it all. When we were together in Mull in 1973, I persuaded him to go with me to a Wee Free service in Tobermory. The sermon raised fearful ghosts, and he deter- mined never willingly to set foot in such a place of worship again. What he did retain, however, was an unambiguous sense of the distinction between right and wrong, and this gave to all his writing a moral strength which readers relished even when they disagreed with particular verdicts. I often thought George would have made a good judge: both open- and fair-minded, judi- cious at all times, and severe and merciful as the occasion demanded. Indeed, as he grew older and his red hair turned first to pepper-and-salt, then grey, he began to look like a judge. When I pointed this out, he agreed with relish: 'Yes, a hanging judge.' But that was untrue. Behind a mask which some found intimidating, even awesome, there beat a warm, generous and truly affectionate heart, as his family and countless friends well knew. George could roar and fulminate — that was why he was such a success as a television panellist and on his LBC phone-in programme — but as Oliver Goldsmith said of Dr Johnson, 'he has nothing of the bear but his skin'.

George spent some time as a young man in Germany, at Gottingen University, and, like Coleridge — another deep-thinking journalist — absorbed a good deal of German philosophy and history, even if by taste and conviction he inclined more to Hobbes and Hume than Kant, let alone Hegel. His interest in philosophy re- mained, though it became increasingly more of the plain man's than the linguistic variety. George spent a lot of time in pubs, brooding, saying little, listening to the chance conversations of men and women. The fruit of much pondering on life and the world he put into a major work of political theory which he never published, because he could never get it into the shape he wanted. This was one of various projects he was unable to complete. His mind was exceptionally original and he had many gifts — he was a sensitive draftsman and watercolourist, for instance — but asthma and a chronically weak chest robbed him of the extra energy needed to exploit his talents to the full. All the same, George's output was formidable. For many years he was perhaps the best, because the most origin- al, roving correspondent of any Fleet Street daily. He was particularly shrewd about US presidential elections and good at probing into enigmatic places like Mao's China, about which he wrote a vivid and witty book, No Flies in China. He returned there with Margaret Thatcher's circus after she became Tory leader and much enjoyed the junketings. When he got back to London, I said, 'George, what about these rumours that you got tight in Peking and poor Mrs Thatcher had to get you back to your hotel and put you to bed?' 0h,' said he laconically, 'so that's why I found my clothes folded so neatly the next morning. I thought it was those Chinese fellows.' He continued an excellent reporter to the end, though in the last two decades he was primarily a columnist, always in the coun- try's top half-dozen. He greatly enjoyed his stint as editor of this journal. He took over in a difficult time when its future was unclear, and he gave it a pungent and forceful personality, though not one which commended itself to all.

Despite hard work and poor health, George always found time to exercise his gift for keeping old friends and adding new ones. He and his first wife, the exotic and glamorous Patricia Holley — together they had four splendid sons — had a gift for acquiring large houses, usually with ball- rooms, and their weekend parties — espe- cially at Ballast Quay House in Wivenhoe — were unforgettable. At one, there was an open-air performance in the courtyard of Edward German's operetta Merrie Eng- land, produced by young James Gale, in which George's remarkable mother, who still had an excellent voice, sang the part of Queen Elizabeth. It was a grief to all their friends when George and Pat parted after 32 years of marriage. However, George found tranquillity and comfort, back in his native Northumbria, with his second wife, Mary Malone, the former Daily Mirror film critic. By now his health was in- creasingly precarious and Mary's devoted care undoubtedly prolonged George's life for a year or two. He continued working right to the end. After I got the news of his death, I reread his last column in the Daily Mail, published the day before. The tears came to my eyes, for it was as if his voice was in the room, strong, lucid, pithy, to the point, unforgettable.

Previous page

Previous page