A DAY AT THE BAGHDAD RACES

John Simpson waits to be bombed in the capital of Iraq

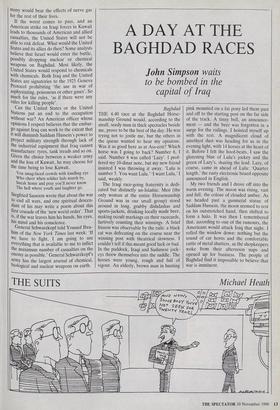

Baghdad THE 4.40 race at the Baghdad Horse- manship Ground would, according to the small, seedy man in thick spectacles beside me, prove to be the best of the day. He was trying not to jostle me, but the others in the queue wanted to hear my opinions. Was it as good here as at Ass-cott? Which horse was I going to back? Number 8, I said. Number 8 was called 'Lazy'. I prof- fered my 10-dinar note, but my new friend insisted I was throwing it away. 'Lulu is number 5. You want Lulu.' I want Lulu,' I said, weakly.

The Iraqi race-going fraternity is dedi- cated but distinctly un-Islamic. Men (the only woman at the entire Horsemanship Ground was in our small group) stood around in long, grubby dishdashas and sports-jackets, drinking locally made beer, making occult markings on their racecards, furtively counting their winnings. A brief frisson was observable by the rails: a black cat was defecating on the course near the winning post with theatrical slowness. I couldn't tell if this meant good luck or bad. In the paddock, Iraqi and Sudanese jock- eys threw themselves into the saddle. The horses were young, rough and full of vigour. An elderly, brown man in hunting pink mounted on a fat pony led them past and off to the starting post on the far side of the track. A tinny bell, an announce- ment — and the beer was forgotten in a surge for the railings. I hoisted myself up with the rest. A magnificent cloud of amethyst dust was heading for us in the evening light, with 14 horses at the heart of it. Before I felt the hoof-beats, I saw the glistening blue of Lulu's jockey and the green of Lazy's, sharing the lead. Lazy, of course, came in ahead of Lulu: 'Quarter length,' the rusty electronic board opposite announced in English.

My two friends and I drove off into the warm evening. The moon was rising, vast and full, the colour of clouded amber. As we headed past a gunmetal statue of Saddam Hussein, the moon seemed to rest on his outstretched hand, then shifted to form a halo. It was then I remembered that, according to one of the rumours, the Americans would attack Iraq that night. I rolled the window down: nothing but the sound of car horns and the comfortable rattle of metal shutters, as the shopkeepers woke from their afternoon naps and opened up for business. 'The people of Baghdad find it impossible to believe that war is imminent. Their leaders seem divided about it. When Yevgeny Primakov, Mr Gor- bachev's personal representative, was here last week, he had difficulties in persuading his old friend Saddam that the Americans and their allies would really attack Iraq if there were no withdrawal from Kuwait. Other senior figures, though, are taking it more seriously. 'We expect our own Guy Fawkes night here on 5 November,' said one anglophile to me wryly. For a day or two the television put out statements which were the Iraqi equivalent of fighting them on the beaches and never surrendering; but, like so much that happens here, the moment faded. A new anti-aircraft gun position has been established on the roof of the big government building near our hotel. Now, my Russian-made telescope shows me, the gunners spend most of their time drowsing against the wall.

I have seen the Iraqi armed forces in action, and not been particularly impress- ed. It was Iranian troops which showed the offensive spirit at their various Pagschen- daeles and Sommes; the Iraqis stayed behind the billion-dollar defensive shield the Russians had built for them, and picked the Iranians off with superior Soviet technology. At the Faw peninsula, cap- tured from Iraq in a night-time amphibious raid which the Iraqis had believed was impossible, I was in a group of observers which endured five hours of bombing by high explosives and chemical weapons during an Iraqi counter-attack. The Iraqi planes were peaceful little silver crosses a couple of miles up in the sky, keeping safely out of range of the futile Iranian anti-aircraft guns which swung around and banged away at them. At Halabje, a couple of years later, I was inspecting some Iraqi tanks which had surrendered to a ragbag of Kurdish rebels, when we were attacked by fighter bombers. They held off until they were convinced we were un- armed.

There were great acts of bravery on the Iraqi side, but their soldiers fought a defensive war against troops with greatly inferior weaponry in positions preselected for their strength. Even so they were lucky not to lose. If there is fighting now, Iraq will find the circumstances very different. Each night a dislikeable man with a blue microphone appears on Iraqi television and interviews groups of soldiers at some unnamed location which looks like the Kuwaiti coast. He always calls on soldiers who praise Saddam Hussein in song and warble sentimentally, while the rest of the group prepare messages for wives and relatives. There is something innocent and rather sad about them: they remind me of the Argentine soldiers who used to chant about the Malvinas and invoke the spirit of San Martin, before the Paras and the Marines set about them. Their equipment looks badly maintained and they are sloppily dressed. They do not seem like conquerors, and my guess is that they don't feel like them either.

Saddam Hussein appears to see things in a different light. If he is planning to stage a lightning withdrawal from all or part of Kuwait to wrongfoot his enemies, he is leaving it very late and doing nothing to prepare public opinion for it, though it could happen at any time. Perhaps he is still compensating for his early bout of nerves when (judging no doubt from his own likely responses in such a situation) he thought the Americans would react to the invasion of Kuwait by launching a nuclear attack on Baghdad. He moved out the city's art treasures: not just the Assyrian bulls, the cuneiform cylinders and the Akkadian gold, but the 4,000 photographs of himself which were on public show at the Saddam Arts Centre.

Baghdad, nevertheless, remains pro- foundly peaceful. In my room on the 12th floor of the Al-Rashid Hotel I feel a little embarrassed about the earnestness of my preparation: the carefully selected impro- ving works of history and literature, de- signed for slow reading over a long period; the 40 CDs, many featuring the Divine Mitsuko Uchida; the tubes of cheese, the tins of smoked oysters, the field dressings, the pain-killers. I conserve paper absurdly by writing articles like this one on the cardboard from laundered shirts. The Robinson Crusoe spirit has settled on me, and I see similar signs on others. We are ready for anything the US air force should throw at us.

Yet, as long as it fails to throw anything at us, there is a certain sense of being all dressed up with nowhere to go. I hope profoundly that there will be no attack, because I have grown to like Baghdad and its people; but it's not hard to understand what one hostage from London meant when he said on 5 November: Today's the day. Can't 'appen fast enough for me. I just want something to 'appen, that's all.' His policy for the war would be that of the Daily Beast: a few quick patriotic victories and a colourful march through the capital.

As for me and the people like me, we spend a lot of time nowadays looking out of the window of our rooms high up in the Al-Rashid Hotel. We look at the woods, the park, the occasional blue-domed mos- que, the minarets; and, on the other side of the hotel, at the mud-coloured buildings, the palm trees and the radio masts. The full moon rides high over the place where the circular city of Haroun Al-Rashid once stood. Every trace of that city has dis- appeared, destroyed by the Mongol leader Hulago, Genghis Khan's grandson, in 1258. 'Bomber's moon,' says someone. We laugh, uneasily.

`Apparently Derek's friend is in showbusiness too.'

Previous page

Previous page