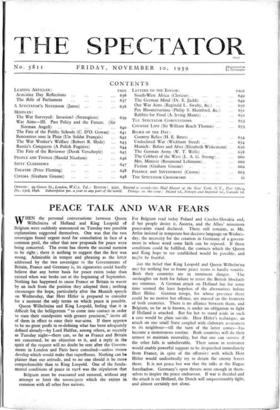

PEACE TALK AND WAR FEARS

WHEN the personal conversations between Queen Wilhelmina of Holland and King Leopold of Belgium were suddenly announced on Tuesday two possible explanations suggested themselves. One was that the two sovereigns found urgent need for consultation in face of a common peril, the other that new proposals fcir peace were being concerted. The event has shown the second surmise to be right ; there is nothing to suggest that the first was wrong. Admirable in temper and phrasing as the letter addressed by the two sovereigns to the Governments of Britain, France and Germany is, its signatories could hardly believe that any better basis for peace exists today than existed when war broke out at the beginning of September. Nothing has happened to cause France or Britain to waver by an inch from the position they adopted then ; nothing encourages the hope, particularly after the Munich speech on Wednesday, that Herr Hitler is prepared to consider for a moment the only terms on which peace is possible.

Queen Wilhelmina and King Leopold, feeling that it is difficult foz the belligerents " to come into contact in order to state their standpoints with greater precision," invite all of them in effect to state their war-aims. If there appears to be no great profit in re-defining what has been adequately defined already—by Lord Halifax, among others, as recently as Tuesday night—there can, so far as France and Britain are concerned, be no objection to it, and a reply in the spirit of the request will no doubt be sent after the Govern- ments in London and Paris have consulted—unless events develop which would make that superfluous. Nothing can be plainer than our attitude, and to no one should it be more comprehensible than to King Leopold. One of the funda- mental conditions of peace in 1918 was the stipulation that Belgium must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. For Belgium read today Poland and Czecho-Slovakia and, if her people desire it, Austria, and the Allies' minimum peace-aims stand declared. There still remains, as Mr. Attlee insisted in temperate but decisive language on Wednes- day, the necessity for the creation in Germany of a govern- ment in whose word some faith can be reposed. If those conditions could be fulfilled, the contacts which the Queen and King hope to see established would be possible, and might be fruitful.

But the belief that King Leopold and Queen Wilhelm;na met for nothing but to frame peace terms is hardly tenable. Both their countries are in imminent danger. The onslaughts on both for failure to resist the British blockade are ominous. A German attack on Holland has for some time seemed the least hopeless of the alternatives before Herr Hitler. German troops, for whose presence there could be no motive but offence, are massed on the frontiers of both countries. There is no alliance between them, and Belgium, so far as is known, is under no obligation to fight if Holland is attacked. But for her to stand aside in such a case would be plain suicide. Herr Hitler's technique, an attack on one small State coupled with elaborate assurances to its neighbour—till the turn of the latter comes—has become a monotonous routine. Both countries will do their utmost to maintain neutrality, but that one can survive if the other falls is unbelievable. Their union in resistance would enable powerful support to be despatched immediately from France, in spite of the offensive with which Herr Hitler would undoubtedly try to detain the enemy forces there. It is not peace but war that the talks at the Hague foreshadow. Germany's open threats were enough in them- selves to inspire the peace endeavour. If war is decided and the attack is on Holland, the Dutch will unquestionably fight, and almost certainly not alone.