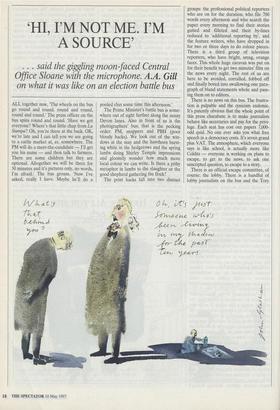

'HI, I'M NOT ME. I'M

A SOURCE'

. . . said the giggling moon-faced Central

Office Sloane with the microphone. A.A. Gill

on what it was like on an election battle bus

ALL together now, 'The wheels on the bus go round and round, round and round, round and round.' The press officer on the bus spins round and round. 'Have we got everyone? Where's that little chap from La Stampa? Oh, you're there at the back. OK, we're late and I can tell you we are going to a cattle market at, er, somewhere. The PM will do a meet-the-candidate — I'll get you his name — and then talk to farmers. There are some children but they are optional. Altogether we will be there for 30 minutes and it's pictures only, no words, I'm afraid.' The bus groans. 'Now I've asked, really I have. Maybe he'll do a pooled chat some time this afternoon.'

The Prime Minister's battle bus is some- where out of sight further along the sunny Devon lanes. Also in front of us is the photographers' bus; that is the pecking order: PM, snappers and PBH (poor bloody hacks). We look out of the win- dows at the may and the hawthorn burst- ing white in the hedgerows and the spring lambs doing Shirley Temple impressions and gloomily wonder how much more local colour we can write. Is there a pithy metaphor in lambs to the slaughter or the good shepherd gathering the flock?

The print hacks fall into two distinct groups: the professional political reporters who are on for the duration, who file 700 words every afternoon and who search the paper every morning to find their stories gutted and filleted and their by-lines reduced to 'additional reporting by', and the feature writers, who have dropped in for two or three days to do colour pieces. There is a third group of television reporters, who have bright, smug, orange faces. This whole huge caravan was put on for their benefit to get two minutes' film on the news every night. The rest of us are here to be avoided, corralled, fobbed off and finally bored into swallowing one para- graph of bland statements whole and pass- ing them on to editors.

There is no news on this bus. The frustra- tion is palpable and the cynicism endemic. It's patently obvious that the whole point of this press charabanc is to make journalists behave like secretaries and pay for the privi- lege. Each seat has cost our papers 7,000- odd quid. No one ever asks you what free speech in a democracy costs. It's seven grand plus VAT. The atmosphere, which everyone says is like school, is actually more like Colditz — everyone is working on plans to escape, to get to the news, to ask one unscripted question, to escape to a story.

There is an official escape committee, of course: the lobby. There is a handful of lobby journalists on the bus and the Tory goons will occasionally deal with them. On my second day, after hours of argument, it is agreed that the Westminster boys can have five minutes with the Prime Minister, off the record, of course, pooled with the rest of the bus and embargoed till mid- night. This is the way they managed the news in the Falklands. The grey, stern- faced journalists emerge. This is a critical moment in the campaign, everything to play for. Hacks starved of news huddle round for the pool like prisoners waiting for Red Cross parcels, and what has the combined brilliance and intellect of the lobby managed to glean? 'The Prime Min- ister today revealed that he could only name two of the Spice Girls but he refused to say which was his favourite.'

I've never had much regard for the lobby. After seeing them at work my con- tempt knows no bounds. They were the quislings of the bus. The lobby don't deal in news, they deal in secrets like servants at a Renaissance court. They are the mes- sengers of intrigue who imagine that the whispers and confidences of the powerful can make them powerful. The lobby sys- tem pollutes all politicians' relationships with the press. The wettest, goofiest little no-hope candidate will puff out his chest and say, 'Lobby rules, this is off the record,' and then tell you something irre- deemably dim. Giggling, moon-faced Sloanes in their twenties pick up the microphone in the bus and say, 'Hi, I'm not me, I'm sources close to the Conserva- tive party leadership and this is off the record. We're going to Plymouth.' Ply- mouth has been D-noticed off the map.

The real journalists get fantastically resourceful at concocting stories out of the merest nothing. My favourite was the chap from the Glasgow Herald who always reeked of home brew even at nine in the morning, who got a thousand words print- ed on the broken wing mirror of Major's bus. 'Seven years' bad luck,' he muttered. 'That'll do me,' and went to sleep.

In one of the many cattle markets the PM had a closed meeting with beef farm- ers afterwards. One of the cattle men men- tioned to a reporter that Major had said he would sack Douglas Hogg. That's a story. Could we tease the press officer with it? `Do you have any comment? We have to file in 15 minutes.' A flustered statement comes back: 'The PM is making no com- ment on Cabinet changes in the middle of 'It's a message from the Conservative candidate.' a campaign. All decisions from the agricul- tural ministry go through his office.' Ah, so he doesn't trust Hogg to do his job properly. That is a story. 'No, no,' whim- pers the press officer who is not quite her- self but a source close to Central Office. 'That's not what he/we/they meant.' Too late: mobile phones are twittering.

The election seen from the bus happens in a parallel universe. The campaign becomes a duel of blast and counterblast, repositioning, rebuttal, feint and sortie, none of which is anything more than distant thunder to the voter at large. Any politician who says he's hearing the truth on the nation's doorstep is lying or sorely deluded. We arrive in small towns like visitors from space in a Steven Spielberg movie. Our very presence makes everything phony. Major probably meets four real people a day and they're so awestruck they would tell him anything. In a small rural town in Yorkshire, while he was doing the stump business and the hacks were all looking for the makings of a story I approached a woman to get her views on monetary union or fish quotas or the weather, but she got in first: 'Oh, you're you, aren't you? Oh we love you on the telly, can I take a picture?' Coming round the outside of the crowd was Ann Leslie, the doyenne of gravel-voiced been-there- done-that hackery (Darling, the one thing I don't do is walk), holding a huge gold- wrapped box of chocolates. 'A fan, darling, just rushed into a shop and bought it for me, dear.' I didn't mention my encounter. I'd been trumped.

As I sat next to Rian Malan, the South African writer and anti-apartheid campaign- er, and he talked in a quiet way about their elections and what they meant; it made me feel rather ashamed. I wanted this process to be impressive, to be awesome, befitting the mother of all democracies (it's England, not Westminster, that is the Mother of Parlia- ments, by the way). I'd wanted to be impressed, to feel that I'd had a small role in the greatest achievement of civilisation, a peaceful election held under the eye of a free press. But I wasn't. The means have become the ends. The politicians and jour- nalists both have an equal stake in freedom of speech and argument for the benefit of their readers and voters, but the process is mired and gagged by obfuscation of the record, subterfuge, lies, blackmail and threats of expulsion. At least on this bus it is.

On one level it was quite fun — I like the company of journalists, they are amusing and gossipy and clever — but on a deeper level it was humiliating and shameful. We are cyni- cally playing fast and loose with our most precious possession, tugging at the fabric of democracy. I met John Major only once, briefly and by accident. He came upon me in a crowd, looked at my press pass, smiled, shook my hand and said, 'I know what you want, you want an off-the-record quote.'

Previous page

Previous page