Exhibitions 1

Refigured Painting: The German Image 1960-1988 (Kunstmuseum, Diisseldorf, till 30 June; Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, September—November)

Echt Deutsch

William Hardy

The Germanness of Geman art has always encouraged foreigners to cordon it off. This has been much easier to do in the last 15 years as the German issue has grown ever more prominent and as pain- ters have used it more directly in their work. In earlier post-war decades any national identity in German art was largely submerged under the bland anonymity of an international-style abstraction that mir- rored the sleek and discreet new Federal Republic.

Those days are now long gone. Today, as Germany turns more towards the east again, it is worth noting that much of the energy of the resurgence in painting has come from the other Germany over the border. Baselitz, Schonebeck and Penck are all from Saxony, the home of such model export-material Germans as Fried- rich, Wagner and Nietzsche. The artistic orthodoxy they encountered in the GDR was more stifling than in the West, a socialist realism that 'depicted anything but reality', in the words of Gunther Grass, but which at least offered a useful signpost to the future in the use of figurative imagery.

Nowadays, ironically enough in the light of post-war qualms, German art cannot be German enough for its fashionable interna- tional audience. This is especially true of New York, where this show was first seen at the Guggenheim. There, an art that deals with serious political and historical subjects can indeed seem truly exotic. The exhibition enshrines one view of recent history: German painting discovers the figure, discovers its soul and returns to the high table of world culture.

Fortunately the exhibition goes further than just showing salvation through the figure and an expressionist heritage. It presents not a school of painters, but a collection of jostling personalities with the energy to draw together a wide range of sources. The abstract versus figurative battle has been dead and buried in Ger- many since Baselitz created his upside- down world in the Sixties and discovered a comfortable area between the two. A `figurative' label tells only some of the story, when painters are pushing towards an expressive goal with all the means at their disposal. There is overall a real sense of freedom in the show, with a healthy sense of proportion between style and content.

A lot of this confidence and authority comes from a generation of painters now approaching their prime. On one side there are Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, who have both worked through the cere- bral path of images from photography and popular culture to produce the Seventies form of cool high art that has become famous for leaving so many people blank and rather unsatisfied. Both are now pro- ducing rich and very painterly abstractions that allude to spirituality without callow pretension or self-consciousness. Polke's are light and sublime, Richter's dark and dense. Against these there are also the famous images of what now seems to be the first heroic phase of the new 'figurative' wave in the late Seventies and early Eighties. The titles sum it all up: Penck's 'Quo Vadis Germania', Immendorf's 'Café Deutsch- land IV'. These and others have become identified with the general cathartic treat- ment of the national psyche, but now the air has been cleared a little, something fresher and more invigorating is emerging. Marcus Lupertz is a good example. Born in the Sudetenland, he has painted a Germa- nic debris of helmets, axes, spades aban- doned in a landscape as if by an army or a people in retreat, as his family must remember them from their flight to the Rhine after the war. Now his horizons seem broader, and his latest works using natural and semi-invented forms, are far richer, more attractive, even entertaining, and successfully match their higher ambi- tions.

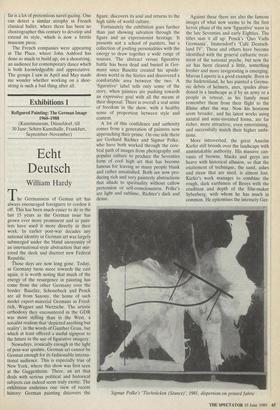

More introverted, the great Anselm Kiefer still broods over the landscape with unmistakable authority. His massive can- vases of browns, blacks and greys are heavy with historical allusion, so that the excitement of technique, the sand, ashes and straw that are used, is almost lost. Kiefer's work manages to combine the rough, dark earthiness of Beuys with the erudition and depth of the film-maker Syberberg, with whom he has much in common. He epitomises the intensely Ger- Sigmar Polke's 'Tischracken (Seance)', 1981, dispersion on printed fabric man art that paradoxically travels so well.

Behind these big names there are plenty of other figures who add more distinctive colouring. There is the Mediterranean monumentality of Hermann Albert's fig- ures, or the glittering oriental opulence of Michael Buthe's Moroccan paintings. Very German, perhaps, to escape to the south, but also very refreshing to escape from the lacerating slashes of born-again express- ionism, of Van Gogh, Bacon, Berlin and the Wall. That work is here too, and is done well, perhaps in its purest and best form by Rainer Fetting. But on the whole this is the sort of typecasting that infuriates many Germans and this exhibition helps put it to rest.

Previous page

Previous page