In the Air

By JOHN BULL

us-RoYcE and Bristol Aeroplane have de-

cided to begin the reorganisation of the British aircraft industry. And in so doing they upset two commonly held notions: that there could be no reform until the civil as well as the military work-load of the 1960s was fixed; and that the first step would be a merger between Hawker Siddeley's airframe interests and the British Aircraft Corporation.

The 1966 Defence Review showed what mili- tary orders can be expected, but about civil air- craft there are still important decisions to be made. On which side of the Atlantic is BEA to buy the 'commuter' jets it will need in 1968? Is there to be an Anglo-French air-bus ready for service in the early 1970s and who will make it? Finally, on what scale is the Concorde project to be backed by the British and French governments?

In fact. it is tempting to argue that Rolls- Royce's desire for a merger with Bristol Aero-. plane .(whose major asset is a half share with. Hawker Siddeley in Britain's only other aero. engine manufacturer, Bristol Siddeley Engines) suggests that the answers to these questions have already been guessed in one or two board rooms.

The first point to notice in this connection is that Rolls-Royce has an enormous order book for Spey engines (they are going into the Phantoms, the Maritime Comets and the Buc- caneer fighters which the RAF and . the Royal Navy are to have). As a result, the group has had to sub-contract some of the work to Bristol Siddeley Engines (BSE), which had spare capacity owing to the cancellation of the TSR-2 project. But if BEA is to purchase British 'commuter' jets in 1968, then the Spey order book will swell to even more unmanageable proportions.

Secondly, the engine which is likely to go into the Anglo-French air-bus is the one proposed by BSE, together with SNECMA of France, and Pratt and Whitney of the US, rather than the Rolls-Royce candidate. And here is another reason why, a Rolls-Royce/BSE merger would make good sense.

Rolls-Royce has a great deal of production work to do for the rest of the decade, but it has not got many orders in sight thereafter. BSE, on the other hand, will spend the late 1960s on developments which will not go into production until the early 1970s. As well as the air-bus engine project, it has the power-plant order for the Concorde (again a joint venture with SNECMA) and also the contract for the Anglo-French variable-geometry aircraft engine, a requirement which the Defence Review described as 'the core of our long-term aircraft programme.' The two order books, indeed, fit nicely together.

The importance of the Rolls-Royce/Bristol talks, however, extends further than considera- tions of capacity and order books. In order to gain the full commercial benefits from BSE, Rolls-Royce must also wish to purchase Hawker Siddeley's half share-you can do things with 100 per cent control of a company which you cannot do with less. Furthermore, it seems most unlikely that Rolls-Royce wants to be saddled with Bristol Aeroplane's other investments: that is, its 20 per cent share of the British Aircraft Corporation, its 15 per cent stake in Short Brothers.and Harland and its 10 per cent holding in Westland Aircraft. These interests are now foot-loose. And there is one obvious buyer.

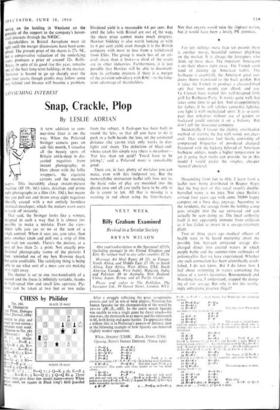

The Ministry of Aviation announced last February that the Government wanted a share- holding in the airframe side of the industry. HMG already owns around 70 per cent of the equity of Short Brothers, so another 15 per cent would not harm. And it would be easy to justify laying on the holding in Westland on the grounds of the support to the company's hover- craft interests through the NRDC. Shareholders in Bristol Aeroplane must sit tight until the merger discussions have been com- pleted. The present price of the shares is 27s. 9d., but a conservative valuation of the underlying assets produces a price of around 32s. Rolls- Royce, in spite of its good rise this year, remains one of the best long-term holdings in the market. Turnover is bound to go up sharply over the next four years, though profits may follow some nay behind and finance will become a problem. Dividend yield is a reasonable 4.6 per cent. But until the talks with Bristol are out of the way, the share price cannot make much progress. Hawker Siddeley is also worth looking at with its 6 per cent yield, even though it is the British company with most to lose from a withdrawal from Eldo. The group is much less of an air- craft share than it looks—a third of the assets are in other industries. Furthermore, it is just possible that Hawker will be able to deconsoli- date its airframe interests if there is a merger of the aviation subsidiary with BAC—to the long- term advantage of shareholders.

Previous page

Previous page