Exhibitions 1

Copier Creer. De Turner a Picasso: 300 oeuvres inspires par les maitres du Louvre (Louvre, Paris, till 25 July)

The great art of copying

Alasdair Palmer

In July 1793 France's newly constituted revolutionary government took time off from guillotining aristocrats to order the foundation of 'a central museum of arts . . . in the gallery which runs from the Louvre to the Palais National'. The Louvre was still warm from its previous occupant, Louis XVI, who had been executed a mere six months earlier. Its conversion into a gallery solved what was turning into a pressing problem: what to do with Louis's `pictures, statues, vases and precious furni- ture', not to mention one of his more glori- ous palaces. It was a bold stroke, even for the revolutionary government. In 1793, almost every work of art in the world was either in a church or in a private house. There were no 'national galleries' any- where.

Art and revolution expanded together. The decapitated King's collection was enlarged not by new works by French artists, but by pictures looted from revolu- tionary conquests: 75 works by Rubens from the conquest of Belgium alone, not to mention dozens of pictures by Rembrandt and Van Dyck. The biggest haul of all came from Napoleon's conquest of Italy. The masterpieces stolen here were thought so important that a triumphal parade was organised for their formal entry into Paris. It was headed by 15 works of Raphael in a special carriage drawn by plumed horses. The pictures were trailed in front of top government officials, to vast public acclaim, before being installed in the new gallery.

Despite the degree of popular enthusi- asm that greeted their arrival, the govern- ment did not make it easy for the people to see the pictures. The original Louvre muse- um was conceived more as a school than a public gallery: working artists could con- template the masterpieces exhibited there any day of the week, but mere mortals were only allowed in at weekends. The artists repaid the compliment first by producing magnificent copies of those gorgeous, loot- ed Italian masterpieces and eventually by creating great works of their own.

Celebrating its bicentenary, the Louvre has organised an exhibition around the way artists over the past 200 years have responded to the Louvre's collection. Delacroix, the greatest of the 19th-century painters, wrote, 'Copies and copying. That has been the education of almost all the great masters', and this exhibition is a glori- ous testament to the creative power of imi- tation. From Turner's small notebooks, each page filled with a delicate study of Titian or Claude, to Cezanne's exquisite copies of Rubens or Picasso's frenzied reworking of Delacroix's 'Femmes d'Alger', it is fascinating to see how one artist shapes, and is shaped by, his response to another.

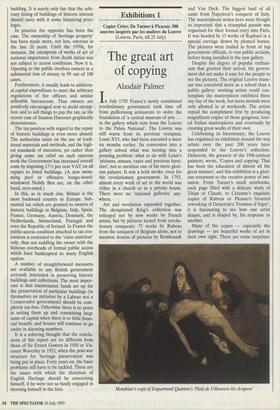

Many of the copies — especially the drawings — are beautiful works of art in their own right. There are some surprises: Mondrian's copy of Enguerrand Quarton's 'Pieta de Villeneuve-les-Avignon' the most unrelentingly accurate copy in the whole exhibition is one of a 15th-century Avignon Pieta. The author of the copy is Mondrian. There is a minutely observed copy of a 15th-century enamel of St Christopher by the 20th-century architect Le Corbusier. Matisse draws an antique statue of Hermes in uncharacteristically flawless academic style, whilst Matisse's academic teacher Moreau imbues his own drawing of Giorgione's 'Le Concert cham- petre' with all the delicate simplicity of Matisse's late sketches.

The exhibition is chronologically ordered. Nowhere is the sudden cut-off in European art around 1920 more evident than in the final rooms of this exhibition. Almost simultaneously, artists stop copy- ing. The dominant response to the work of previous painters ceases to be inspiration and becomes fear: the terrible anxiety of influence replaces the creative impulse to learn, compete and surpass. To copy sud- denly comes to mean merely to imitate which means to fail to be original. And that, now, is the worst crime of which an artist can be guilty. Soon the only accept- able response to the past is parody, a kind of sarcastic smile at a predecessor's lack of philosophical sophistication, and at those stupid enough still uncritically to admire him. There are plenty of examples of that attitude in this exhibition, including one of its earliest and most famous incarnations, Duchamp's moustaches and beard drawn on the Mona Lisa.

The contempt for copying has been catastrophic for the craft of painting. As this exhibition shows, great artists did not become as skilled as they were in handling paint by accident. They achieved it by imi- tating the greatest technicians of the past, thereby discovering exactly how their mira- cles were achieved. Without that level of study, the degree of dexterity achieved is distinctly unmiraculous.

The wholesale rejection of copying is also based on a straightforward mistake. Imitation is not the enemy of artistic origi- nality and creativity. It is a necessary step to achieving it. In an age in which we are surrounded by exact photographic repro- ductions of everything — from hotel book- ings and minutes of meetings to Van Goghs and Monets — it is easy to forget that the perfect, mechanical copying achieved in an instant by fax, Xerox or Polaroid cannot be executed by the human hand. No two copies of the same work by different artists are ever the same. On view in the exhibition are copies of Delacroix's la Barque de Dante' by Manet, Cezanne, Feuerbach and Cals. Whilst all of them did their best to capture the original as accu- rately as possible, each painting is different from the others in hundreds of ways. Not one of them was trying to be original: the imperfections and idiosyncracies of the human copyist are the source of his creativ- ity. The camera cannot lie — but that is why it cannot create great art, either.

Previous page

Previous page